Epilepsy Insights

Impatient series #4 – The place for patients in preclinical research

Once there is a drug that has been developed, it is very clear why talking with patients and collaborating with them is useful for pharmaceutical companies. What is less obvious to both companies and patient organizations is how patients can be active in research before there is any drug in development, during the preclinical phase, and how this might lead to medicines being developed. Some patient organizations might start by funding some academic group, but without a clear vision and a longer-term strategy the return on those efforts will be compromised, and medicines will take longer to come. Here I want to outline the broader strategy that patient organizations can follow to advance research towards new medicines even before companies are working on it.

Once there is a drug that has been developed, it is very clear why talking with patients and collaborating with them is useful for pharmaceutical companies. They often learn about the disease from patients, so that they can better understand the symptoms and how to design clinical trials. Patients are also involved at different stages in the regulatory pathway, providing feedback to the regulatory agencies during trial protocol approval, orphan drug designation or marketing authorization.

What is less obvious to both companies and patient organizations is how patients can be active in research before there is any drug in development, during the preclinical phase, and how this might lead to medicines being developed. “Preclinical” refers to the research that is done before a therapy can be tested in patients. Some patient organizations might start by funding some academic group, but without a clear vision and a longer-term strategy the return on those efforts will be compromised, and medicines will take longer to come.

What follows is my advice on how to approach early-stage research for those interested in advancing research from a patient organization. My main advice to patients working on a disease is to “own” the field, don’t leave this up to academic scientists.

To focus on advancing the research field means more than funding a couple of research programs. I list many specific research programs that are important early on in a field in the eBook the #ImpatientRevolution. Here I want to outline the broader strategy that patient organizations can follow to advance research towards new medicines even before companies are working on it.

1) CONNECT

A key value that patient organizations bring to a research field is to create communication channels between the different researchers working on it. This might be formalized, like hosting an annual scientific meeting, or more informal, simply by knowing everyone in the field and introducing them to one another. By creating these connections researchers start collaborating and have improved ability to obtain funding as they bring key collaborators onboard. So no only research will be improved by increased communication, but also this community will be able to mobilize more public funding towards their rare disease by building a stronger scientific base. The way to start these connections can be as simple as reaching out to corresponding authors in PubMed publications related to your rare disease, and by always asking “who else do you recommend me to talk to?”.

2) TOOLS

For scientists to work on a rare disease, or any disease in general, they need to have a tool box. These are research tools, without which scientists cannot build the science. Research tools include animal models of the disease, cell lines (lab cells expressing the disease protein or patient-derived cells), antibodies that recognize the disease protein, or the DNA of the disease gene that is then used to create these models. For anyone to research a rare disease, they are going to need to use these tools.

Because they are so necessary, scientists who are the first to invest the time and resources to create those tools might hold on to them, limiting who else can work in the field. This happens very often in rare diseases, when only one lab has a knockout mouse model for the disease, or has the only good antibody for that protein. Keep in mind that academic science is very competitive, and being the only lab in the world able to do something is highly prized. This creates the incentive of not sharing, and seeing other labs wanting to work on the same disease as competitors.

Don’t let any scientist decide who can or cannot do research in your disease. Build all these tools yourself and make them open-access – or if you finance a lab to build these tools make sure your funding contract makes it mandatory for them to share it with anyone afterwards, for-profit companies included, without being able to veto anyone.

By making sure your rare disease has the complete toolbox available to all scientists you will mobilize a large number of researchers towards your disease. You might also start to attract pharma companies. Reducing the barriers of entry to your field is one of the best things you can do as a patient organization.

3) KEY QUESTIONS

Beyond investing in building the toolbox, you need to identify which are the key questions around your specific rare disease that might also represent a barrier of entry for researchers and pharma companies. It might be that the incidence of the disease is unknown because the first handful of patients has just been described. It might be that the disease is caused by a mutated kinase, and the targets of this kinase are unknown. It might be that the rare disease involves the deletion of a chromosome fragment involving dozens of genes, and the individual gene(s) among all these which is responsible for the disease is unknown. These are all some examples of important questions that are important to solve before therapies can be developed for this disease. If these are still unanswered, as a patient group these should rank very high in your priority list.

I recommend targeting these questions by approaching labs that have already solve this type of questions, even if they are not yet interested in your disease. They are much more likely to be able to complete these projects successfully than labs that you might already be in contact with, who are already familiar with your disease, but who lack the core expertise to ask these questions. You don’t have the time to wait around labs developing new skills, you should try to put together the research tool box and solve the key questions as soon as you can so that a large group of scientists (and potentially pharmaceutical companies) start working on developing therapies for your disease.

4) FAST MEDICINES

Remember the importance of developing the toolbox? One of the early uses of having cell lines and animal models for your rare disease is to be able to find a new drug the fastest way possible: by finding a new use for an old drug.

You will most likely hear early into your journey about drug repurposing. Drug repurposing refers to finding a new use (a new purpose) for an already existing medication, which enables doctors to use it to treat this new disease as well. In some cases there will be clinical trials to seek approval for using that drug in the new disease. In most cases there won’t be clinical trials, and doctors will simply prescribe it off label. In either case as a patient group one of the earliest questions that you should aim to answer is whether there is a drug already out there, sitting at the pharmacy shelf, that could potentially treat your disease. The best way to do this is by using cell lines expressing your disease protein or gene, or by using small animal models such as yeast, c. elegans or zebrafish (the choice depends on the particular rare disease), and use them to run a screen of approved drugs, looking for those able to restore protein function or address a particular disease phenotype. Running a repurposing screen to identify any potential drug that is already available should also very high in your priority list.

A 2.0 version of these efforts is to use those cell lines or animal models to evaluate drugs already in clinical development for related diseases. If you identify a drug with efficacy, the company that is developing it might be interested in expanding those clinical trials to include patients with your disease.

That’s why it is so important to consider all the drugs already developed (or near approval), because if you find a drug that is already approved or in clinical trials and that has efficacy in your disease you will be cutting down by many years, potentially a decade, the wait for new medicines.

5) ENGAGE PHARMA – EVEN AT THE PRECLINICAL STAGE

Last, I still recommend you to try to engage with the biotech and pharma industry as early as you can. Ask them about how they see your disease. Do they see it as similar to another disease? Perhaps similar to a large disease? Do they flag some immediate research gaps? This feedback will help you shape your research strategy as you build a relationship with the industry and learn to think about therapy development.

But these conversations are often not happening, or are not happening early enough. The reasons are multiple on both fronts:

What patient organizations often want when collaborating with companies before there are drugs in clinical trials

Most patient organizations are in touch with companies that have a drug in clinical trials for their disease. Patient organizations that approach companies before these companies have a drug so advanced are often interested in trying to convince the company to work on their disease. Because in most cases this will simply not happen, it is best if the patient groups can switch their focus to learning to understand how industry scientists think about diseases and get their input about their rare disease field. They can also be good door openers if they know people in other companies.

What companies often want when collaborating with patient organizations before there are drugs in clinical trials

At early stages, before they have a drug in development for that disease, industry scientists are interested in learning about a disease beyond what is already published in the medical literature. They want to know what the incidence of the disease is, if there are centers of excellence, and many of the questions I covered in the “when is your disease field ready to attract the interest of companies” article earlier in this Impatient Series.

What holds patient organizations back from collaborating with companies before there are drugs in clinical trials

Patient organizations sometimes refuse to engage with pharmaceutical companies because they believe it creates a (perceived) conflict of interest. They think it is better to remain on the academic science side, and not collaborate with companies. Academic scientists don’t think the same way that industry scientists, and don’t have the same incentives (publications vs drugs approved), so it is a mistake to believe that academic scientists can replace the work and input of industry specialists. My advice is to avoid perceived conflict of interest or biases by simply engaging with every single company in your disease field, without picking favorites, and to make sure they have as many information as they need (see previous section).

What holds drug development companies back from collaborating with patient organizations before there are drugs in clinical trials

People working at pharmaceutical companies usually express the same two fears that keep them away from engaging patient organizations early in the preclinical stage or even before they decide to start a program in a disease. One is disappointing patients. They think that by talking to a patient organization, patients and their families will think that this company will develop a drug for their disease, be successful and reach the market. Industry scientists know that most programs will not even reach clinical trials, so they are worried about disappointing patients. I find it interesting that when I have talked to patients about this they often tell me that talking to companies and knowing that companies are interested in their disease makes them feel more at peace, versus worrying that no one is doing research or developing a drug. Living with a rare disease is hard enough, patient don’t think there is going to be a perfect cure developed overnight, they rather express the need to know that efforts are ongoing and that they are not alone at trying to look for a medicine.

The second main fear that industry employees express is lack of confidentiality. I will want to address this in a future entry in the Impatient Series. It is important for patient organizations to remain professional, and not disclose confidential information when they have access to it. If they do, they will stop knowing about things before the news are public and they will not be able to influence important processes like clinical trial protocol design early enough to make an impact.

IN SUMMARY, WHAT I RECOMMEND BASED ON MY EXPERIENCE

- Own the field. Be a field expert, not just a patient expert.You will do this by knowing everybody, putting together the room where conversations happen and having developed (or made available) the research tools.

- Be professional about it.Get advice from professionals, get advice from the industry, and if you are willing to invest funds in research then get professionals onboard that help you manage that.

- Collaborate with everyone – or at least talk to everyone - if they are professional about it. Don´t marry a lab, don’t avoid companies to remain free of conflict of interest. Ask to be treated with respect, for example by getting some feedback or update after you have met with a company to provide feedback on some of their work.

Let’s start an #ImpatientRevolution!

Ana Mingorance, PhD

Impatient series #3 – When is your disease field ready to attract the interest of companies

In the previous entry we discussed the many types of companies that get interested in rare diseases, each of them because of different reasons. If your disease field matches one of those business propositions you will get at the top of the list of interesting diseases for that company, but another part of the decision equation is time, or field maturity. Is this field ready for us to start working on it already The following are the questions that a company will often need to answer to be able to judge if the field is ready for them, too early for them, or maybe even too mature for them to get in.

In the previous entry we discussed the many types of companies that get interested in rare diseases, each of them because of different reasons. If your disease field matches one of those business propositions you will get at the top of the list of interesting diseases for that company, but another part of the decision equation is time, or field maturity. Is this field ready for us to start working on it already?

The following are the questions that a company will often need to answer to be able to judge if the field is ready for them, too early for them, or maybe even too mature for them to get in. Some of it applies to both large and rare diseases while some of the questions are more important for rare diseases.

If you work at a rare disease patient organization or research foundation, make sure you also ask yourself these questions:

o How many patients are out there? Some companies will be interested in diseases with as little as 500 patients, but others might have a cut off of 3,000-5,000 treatable patients. If the numbers are not known, or if they are too small, the probability of getting a company interested will be much much smaller.

o Is there already a drug approved that treats this disease in a satisfactory way? If a company can be the first-to-market it will be more interested in the disease.

o Who else is developing drugs for this same rare disease? The larger rare diseases might support competition, with multiple companies hoping to get a piece of the market, but if the disease is very rare one of the main drivers of companies to choose a rare disease, which is avoiding competition, will not make sense anymore.

o Do we know the cause of the disease and what is affected? This will help them see if your disease is a good match for their drug or technology, and even to see if they might have already have some already developed drug that could help your disease because it acts on the same signaling pathway.

o Are there good animal models of the diseases? Generally this is a mouse model. If there are good mouse models the company could either quickly test their drug to see if it has efficacy (if the drug already exists), or use it to confirm the efficacy of a future drug that they might want to develop. If there is no mouse model yet, some companies might worry that the disease might turn out to not be easy to model in a mouse, and that will make it harder to validate their drug in a relevant model prior to clinical trials. In some diseases, other animals are used to model the disease. What matters is if there is a good animal model that has symptoms in common with the patients or not, and if the company can have access to it.

o Are there other preclinical models available? The good mouse model is the bare minimum, for many research programs they will need to have access to DNA carrying the mutation and to cell cultures from patients.

o Is the patient population homogenous? Is there well-documented natural history? This is important to know which are the symptoms that need to be treated and to reduce patient variability. Patient variability is one of the problems of larger common diseases, and the reason of many trials failures. Therefore having patients that are very homogenous (diseases caused by one gene, for example) is a major attractive point of rare diseases.

o Could we find clinical centers willing to run clinical trials and patients willing to enrol? If there are too few specialists or they are not confident that they could find patients, companies will wait for the field to be ready.

o Would we know how to design a clinical trial? Depending on the disease symptoms it might be easy or not to know what could be measured during clinical trials to investigate drug efficacy. Not having a clear symptom to measure in a trial, what is generally called “an endpoint”, can be a major cause of clinical trial failure.

o Is there any previous case of regulatory agreement or approval? If the regulatory authorities (generally FDA or EMA) have already agreed with another company which endpoints are good, and how many patients are needed, and confirmed that they consider that rare disease a legitimate separate disease, then a lot of the regulatory risk has been lifted and more companies will be interested.

Because it takes time to be able to answer all of these questions in an affirmative way, some of the most recently described rare diseases will not be mature enough for companies to work on them. The next entry of the Impatient Series will address how, from a patient organization, you can advance research in your disease to the point and make it mature.

Let’s start an #ImpatientRevolution!

Ana Mingorance, PhD

Impatient series #2 – What are companies looking for when choosing a rare disease

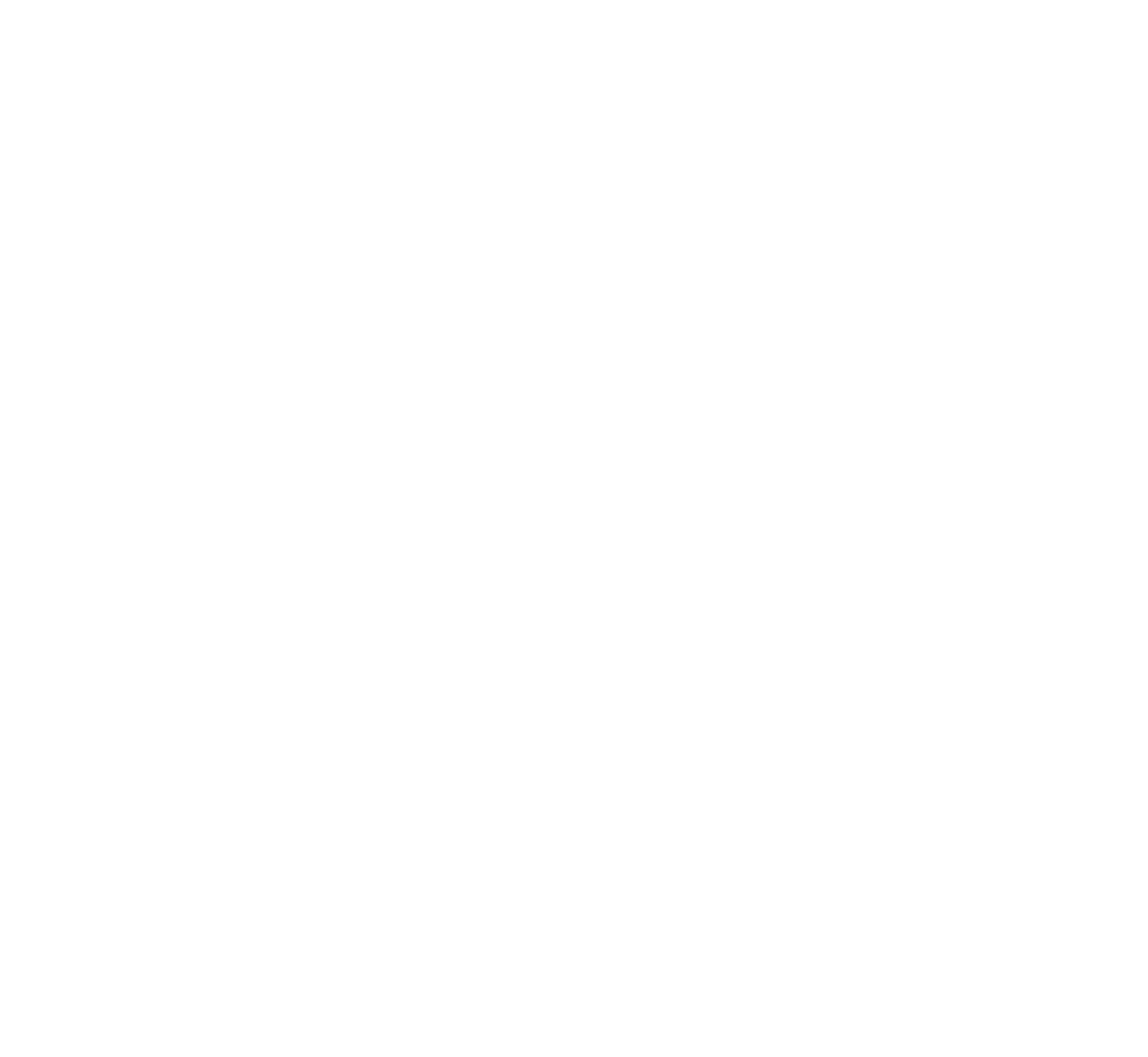

The number of orphan products in development keeps growing every year. A particular rare disease will be attractive for a drug development company if it matches one of four main business propositions determined by the interplay of market pressure and technology enablers. The degree of maturity of a field will also attract companies and help prioritize which disease to focus on where multiple rare diseases match the needs of the company or the drug that they are already developing

As part of these Series I will write about what patient organizations can do towards advancing research, even before a company gets interested in their disease. But before I can address that, we need to first define what gets companies interested in a disease in particular. That will then serve as the goal for patient groups: get your disease field to the point where it can attract companies.

As a side note, some diseases will be so rare that they won’t be able to attract companies. In those cases, if patient organizations need to carry out all of the research and development activities, they will still need a field that is mature enough to support drug development efforts.

I will address this in two parts: first, why companies get interested in rare diseases, and second, why do they choose one rare disease vs another.

PART 1 – CHOOSING ORPHAN

The number of orphan products in development keeps growing every year. Therapies are called orphan when they target a rare disease, which were traditionally orphan in the sense of not having any medicine to treat them. But nowadays some rare diseases have multiple “orphan” drugs to treat them, such as cystic fibrosis, and they are still called orphan drugs.

Companies have been driven towards rare diseases for a combination of reasons. The main ones are probably a market push (away from large markets) and a technology pull (towards rare diseases):

A market push: some of the larger markets got so crowded that it became very difficult for companies to get a competitive price. This has been called the “better than the Beatles” problem. Imagine if every new musician would need to show that they are better than the Beatles in order to get a record out – this is what new drugs must demonstrate in order to get approved and be successful in the market. The rare disease space, however, represents a broad landscape of virgin diseases, for which no drug (or Beatles' song) has ever been approved, and where an effective and safe drug will be commercially rewarded.

A technology pull: with the development of new technologies, particularly genomics, we have been able to understand that what we thought were common diseases are in fact a collection of separate (genetic) rare diseases. Other technologies such as gene therapy and antisense therapy have also enabled us to treat these diseases, in a way that we could have never imagined some years ago.

Drugs developed to treat rare diseases also enjoy of some regulatory and market incentives, which were developed by the regulatory agencies to attract drug developers to this space. The most valuable one is probably the 7 to 10 years (US vs EU) of market exclusivity after approval during which no competitor can have a similar drug approved for the same disease (a generic). But this aspect is less important for patient organizations. Instead we should try to understand how the market and the technology might drive a company to our rare disease.

Looking at the interaction between the market push and the technology pull we can differentiate 4 types of companies that get interested in rare diseases or 4 types of programs within a company that might be directed towards a rare disease:

1- Companies that want large markets and use old technologies: These are your classical large pharma companies, that have the pockets that are needed to pay for clinical development in large diseases, and that are developing a traditional drug, usually a small molecule that can improve an important symptom. These companies have transformed the way we treat common diseases like diabetes or cardiovascular diseases and still produce the same type of drug, but today the problem is the market push that scares them away for the large diseases because there is too much competition and the requirements for pricing and reimbursement are too high. This is how a company that had a drug perfectly good for a large market, and that prefers large markets, finds itself developing their molecule for a rare disease that has that common symptom in order to avoid the competition.

2- Companies that want small markets and use old technologies: Some companies develop the same type of molecule that could treat common diseases but have decided to focus on rare diseases as part of their business model. This is usually the case of smaller companies, which don’t have sufficient money to go after the common diseases. Smaller companies often focus on smaller diseases because those are the ones where they can afford to take a drug all the way through clinical trials and into the market. A second type is when the molecule is an old drug. In these cases the orphan drug market exclusivity that I described before becomes very important and makes the company focus on a rare disease so that they can have product protection (since they don’t have a patent on the drug because it is an old drug). These companies focus on rare diseases because it is cheaper to take orphan drugs to the market and because of the market exclusivity.

3- Companies that want large markets and use new technologies: Some of the large companies, which like to go after large diseases, are also adopting new technologies. This allows them to go straight to the cause of the disease, in what we could consider personalized medicine. In these cases where the therapy targets a disease cause, not just a symptom, rare diseases that share that cause become very attractive as part of the drug development pathway. Imagine for example a company that wants to develop a medicine for Alzheimer's disease by creating a molecule that targets the protein “tau”, which is very important in Alzheimer's. Such company knows that most trials in Alzheimer´s disease fail, and that they cost many hundreds of millions of dollars. So such company will most likely choose to first test their drug in some monogenic taupathy (i.e. a rare disease caused by a problem in tau) to make sure that the drug does what it should, before risking costly Alzheimer’s disease trials. The rare disease becomes a stepping stone in the development program. This is another scenario in which a company that is going after a large market finds itself developing their molecule for a rare disease in order to de-risk their program.

4- Companies that want small markets and use new technologies: And last we have the companies that are focused around a technology platform that usually means they can target genetic causes. These companies working on new technologies such as gene therapy and other personalized-medicine approaches work on rare diseases because these are largely caused by genetic problems, so they are the perfect match for companies (large and small) that are using the new technologies. These are the companies most likely to specifically develop from scratch a therapy ideally designed for that rare disease, and to target the cause. These are the companies (and the business scenario) most likely to lead to the type of treatments that we could call cures.

Some diseases become popular for only of these business reasons. Others fit multiple boxes. It is important for each rare disease patient organization to identify which of these boxes they fit, so that they know how to target their efforts and conversations.

PART 2 – CHOOSING ONE SPECIFIC DISEASE

Q1 - Does it fit our business needs?

Your rare disease will be attractive for a drug development company if it matches one of the four main business propositions (previous graph):

1 - My drug discovery expertise is in epilepsy. The field of epilepsy got very crowded, with over 30 drugs approved, so pretty much every company in the sector started looking at the orphan epilepsies to avoid the competition. Except for some cases, most of their drugs are molecules that could have easily treated epilepsy in general, since they just treat the symptom (seizures) and not one of the many epilepsy causes. But the companies chose to work on the orphan space to avoid competition. That is how rare syndromes with epilepsy “got lucky”. Prader-Willi might be an attractive target for a company that is concerned about competition in the obesity market. Neurodegeneration is another field where companies are moving towards rare diseases, in this case due to the high failure rate in the larger diseases. If your disease has a common symptom and the general market is saturated it might attract these companies.

2 - A company with an old molecule will most likely be looking for a rare disease due to the need of securing some years of market exclusivity in the absence of a drug patent. Often this happens when the company has discovered a new property that the old drug has, which creates the possibility of developing for that new use. In this case they will be looking for a rare disease that matches that new use, either due to its cause or due to its symptoms. Also, some small companies developing molecules that could treat broad diseases choose to focus on the orphan space because they can't afford the large and lengthy trials that broader diseases demand. One example could be the multiple small companies going after autism, which often decide to target genetic syndromes with autism even if their drug is not specific for the syndrome.

3 - The large company that is targeting a molecular cause of a large disease will most likely be interested in identifying a rare disease that results from that same cause. Some diseases become quite popular as monogenic examples of large diseases. I am a neuroscientist, so I often use taupathies as an example of stepping stone. Gaucher disease also shares biology with some forms of Parkinson, so companies targeting glucocerebrosidase for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease are likely to run their trials first in Gaucher’s disease and only risk moving forward with Parkinson if the drug has good results. There are examples of this strategy in all disease areas.

4 - Companies or research programs that are built around a platform technology often have a series of requirements that the target disease must meet in order to be a good match for the technology. A good example is a great young company called Stoke Therapeutics, which has discovered a way to increase protein levels by targeting a step between the gene sequence and the protein production (excuse my vague descriptions for the sake of non-expert understanding). Because of their particular technology, Stoke is interested in diseases that couldn’t be treated with gene therapy (maybe because the gene is too large for “traditional” gene therapy), that is also not amenable to protein replacement approaches (so the protein cannot be a soluble enzyme, for example), that needs more levels of a given protein (and not less levels) and that has one good copy of the gene for their therapy to act on. Each technology will impose a different set of requirements.

It is important to remember that the same disease might be a good match for one of these technologies AND be mechanistically linked with a broader disease so it can be a stepping stone AND have some common symptom that makes it attractive for the opportunistic companies. In other words, each company might be interested in your rare disease for a whole different reason!

Q2 - Is the field already mature?

The previous question asked whether a particular company should be interested in your disease. The question about field maturity essentially asks if they should be interested in your disease NOW. It will also help prioritize which disease to focus on where multiple rare diseases match the needs of the company or the drug that they are already developing.

We will discuss this in the next entry of the Impatient Series.

In the meantime, let’s start an #ImpatientRevolution!

Ana Mingorance, PhD

Impatient series #1 – What patient organizations mean when they say they are doing research

Most patient organizations, no matter how small, start with the same mission: to raise awareness and funds for research in their disease. But what research are they doing? are they all starting in the same place? and do they all evolve to run the same type of research? In my experience there are many types of strategy and approaches that patient groups take, in particular when they are starting. What a patient organization means when they say “we are doing research”, therefore, hides many different possibilities. The article describes some of these types, and discusses their advantages and disadvantages.

When we could only look at symptoms, there were less diseases. Now that we can also look inside a cell and see specifically what went wrong, we are uncovering new diseases, thousands of them. This means that for a lot of people, the disease that they have or that their child has is quite new to science. So in the true spirit of impatient patients, some of those patients come together and start a patient organization.

Most patient organizations, no matter how small, start with the same mission: to raise awareness and funds for research in their disease.

But what research are they doing? are they all starting in the same place? and do they all evolve to run the same type of research?

In my experience there are many types of strategy and approaches that patient groups take, in particular when they are starting. Although no two are the same, they do fall overall into some big types. To make things more complicated, what a patient organization funds in year 1 has often little to do with what they fund some years later. The field has evolved by then, the organization has evolved, the board members might be different… What a patient organization means when they say “we are doing research”, therefore, hides many different possibilities.

Here are some of the strategies that I’ve seen:

Type 1: We just need to exist

There is a tricky catch-22 situation where in order to raise funds (which you would hope to use for research) you have to already show you are a successful patient organization that funds research. Beyond friends and family, you will have to show most other donors where their money is going and how much of an impact it is making. Essentially: you need to be already funding research.

Because of this, your first few projects are critical to show the world that your patient organization exists and that it funds research. The quality of what you fund is in fact secondary. In many cases the project(s) take place at a university located near the headquarters of the patient organization. This might get you into some local press release, provide you with a scientist to refer to when you need some interviews, and essentially get your ticket punched. Congratulations, you now have a patient organization that does research, and from there you can start building a more solid longer-term strategy.

Type 2: Marry a lab

The first researcher that approaches a patient group, in particular if it is a newly-described rare disease, sometimes goes on to become their official lab. As in the previous case, this often happens with organizations that are just starting off. For the next couple of years, the organization will raise funds to finance research at that main lab, which then becomes a referent in the field for that disease. These patient groups appear to be married to that initial lab.

Getting funding for academic research as an academic lab head is very hard. And if it is a new research area for that lab, it might be impossible. So, for some academic labs, receiving funding from those patient groups is the only way to advance their science during the first couple of years until they have generated enough data and publications about the new disease to be able to receive public funding. In a way, the patient group didn’t marry the lab, instead they adopted the lab until it was mature enough to become financially independent.

This is a good strategy when the patient group doesn’t have enough funds to finance multiple projects or labs and when the field is just starting. In this case, the patient group might choose to focus its resources on building a first solid lab, which will pretty much start building the entire research field. This is how some patient groups are doing research.

This strategy, however, can backfire in many ways. One of such scenarios is when the patient group leadership comes to believe that they should not fund other labs because they owe to this initial lab some loyalty in return for their early support. It blurs the line between grantee and patient group and could lead to big conflicts among the patient group leaders. Another potential negative outcome is not having much to show for after supporting the same lab for several years. This happens when the lab learns to see the patient’s money as easy money and not dedicate enough efforts to the project to make an actual tangible progress, unlike they would do for regular external funding.

In short: it is a respectable strategy to adopt one lab and start building a field, but it must be done with a clear outcome in mind, which is agreeing with the lab that they should dedicate those early efforts towards generating compelling data to become financially independent from the patient group. It must to be bridge funding, and not funding for life.

Type 3: Let the advisors decide

When patient organizations have enough funding to support multiple programs, they often choose to surround themselves with a handful of experts that will become their scientific and medical advisors. In many cases, they ask these advisors to tell them where to invest their research funds.

Often this is done by having an annual call for grant applications and then having the advisors and some external experts that they nominate evaluate the grants and rank them. Then the patient group will fund the top ranked proposals. This is how some patient groups are doing research.

One thing I don’t like about this strategy is that it is often bottom-up, with the external scientific community proposing what they would like to do and the patient group then picking the most scientifically excellent ones. I believe research funding should be more strategic and therefore more top-down, but there are ways to achieve a healthy balance.

My main concern with the advisors deciding where to invest is that in some cases a patient group ends up funding every year the same 4 or 5 labs, which happen to be the labs of their scientific and medical advisors and/or their close collaborators. If one can guess who your advisors are by seeing who you fund, you are an organization that has essentially followed the Type 2 strategy of marrying a lab. You simply have married you advisory board.

The debate inside these organizations after the first couple of years is usually the same:

Board member 1: Why are we always funding these same labs? This endogamy of having the advisors finance their own labs is disturbing.

Board member 2: Well, we chose as advisors the leaders in the field, so it is only natural that we also finance the best research… which happens to be the one coming from their labs.

Board member 1: I am not comfortable with the conflict of interest of having the advisors decide where the funding should go after seeing that so much ends up in their own labs or their friends’.

Board member 2: What should we do then? Remove the leaders of the field from our advisory board? Or stop funding the best research out there?

And then board member 1 leaves the organization.

My recommendation, if you allow your advisors to also receive funding, is to ask them to guide you through what should be the main research priorities but then use external reviewers to score the grant applications that fit those priorities. Ask the advisors to pick the priorities, not the awards. I would also consider having a condition to be part of the advisory board, which is that your lab cannot receive funding from that organization. For good established labs that are indeed the best in the field this should not be a problem (see comment on previous sections about bridge funding).

As a side warning: if you are a scientist considering applying to one of the call for grants of a patient group, make sure you review where their funding is usually going. You might think it is an open call for grants, while in reality it is a closed group of advisors and their closest collaborators getting as much funding as they can out of a patient organization. We all know examples of this.

Type 4: Owning the roadmap - the top-down approach

Anyone who has read the #ImpatientRevolution eBook knows that this is my preferred approach. Patient organizations cannot aspire to outfund NIH or their applicable national research funding body outside the US. What patient organizations can do with their research funds is to complement it, by identifying those areas that are essential for developing new medicines for their disease and that are currently not being pursued (or not fast enough). Then they would focus on those areas, ideally on setting up the basis so that good scientists can be attracted to those areas and bring more (non-patient) funding. This is how some patient groups are doing research.

I won´t extend on this strategy because the eBook covers much of it. But before wrapping up, here are some aspects of research funding strategy that I would like you to consider:

a) Bottom-up vs top-down

Do you want to collect external ideas and fund the best ones or do you want to analyze the field, identify the gaps and address those first?

Depending on your finances I recommend following a top-down strategy only, or a combination of both. For example:

Fund some projects that the organization has identified as a priority for the field. In those areas you identify what is needed and then go out and find the best lab or contract research organization to do that. This is probably the boring science, the type that no academic lab would propose in a call for grants because it is not conductive to exciting publications and promotions. It is, however, needed to develop cures.

At the same time, have your advisors identify where your priorities should be (for example biomarkers and a gene therapy with large capacity virus), and then have a call for grants on those topics. The call for grants would then be evaluated by a broader team, not just the advisors.

b) Projects vs enabling

I believe the greatest return on investment comes from generating the tools that will enable the scientists to then work in your disease and bring in their own external funding. For example, make sure that there is a good antibody, a good mouse model, iPSCs from patients, and that all of this open access. Make sure you have identified and helped set up clinical centers of excellence, and maybe some biomarker or outcome measure. Make sure there is a registry, or at the very list a way to reach out to families (a contact database). This toolbox serves both as a starter package and as a strategy to de-risk the field. With these things in place you will attract researchers and companies to your disease, and they will bring their own funding. They will also be many more than those that you could have directly funded yourself, so you would have mobilized much more funding to your disease than what you could have raised in decades.

Many of those efforts are the boring science, so you will only identify them if you do some top-down thinking and analysis. You should decide what percentage of your efforts and resources should be allocated to the boring science (enabling tools, de-risking the field), and what percentage will go to giving an opportunity to new exciting projects to develop.

c) Organization aging and cycles

Young organizations and old organizations think differently. The first two strategies I covered, for example, are much more common in younger organizations. I would recommend you to revise your strategy every 3 years and see what is working for you and what is not working. Older organizations also tend to grow more complex, and are more likely to engage professional staff.

I tend to work with patient organizations where the members of the organizations are parents of children with severe rare diseases. This has also helped me see another pattern, with parents of younger children being more optimistic and driven and investing in more high-risk projects, while parents of older children being more likely to make safer investments or to even move away from research and into care support programs. A parent of a 3-year old might want to invest in gene therapy, while the parent of a 13-year old might be more concerned with developing devices to assist with mobility issues, for example.

And add to this complexity the burnout factor. I´ve seen organizations that are centered around one person that can last many years, but those that rely on a group of core members can experience changes over time. I estimate a 3-5 year burnout time, before new members need to take over and continue the life or the organization.

Because of this, the same organization in year one is very different to the same organization in year seven. The members are different, the strategy is different, and what they mean when they say “we do research” is also different.

Let’s start an #ImpatientRevolution!

Ana Mingorance, PhD

Impatient series #0 – The impatient series

INTRODUCTION TO THE SERIES - The field of rare diseases, where each disease affects only hundreds or thousands of patients world-wide, is leading this revolution. Their diseases were once orphan to medicine, too rare to receive sufficient attention and investment to move the needle. Today patients take ownership of their research fields, and move the needle themselves. They have become the center of the network and the expert in the room. They are impatient, not wanting to wait for pharma to take an interest in their disease. They are impatient patients and are leading an impatient revolution.

The way that medicines are discovered starts in a lab, either at a university or at a pharmaceutical company, and when the discovery seems promising a pharma company picks it up and spends hundreds of millions of dollars to get it through clinical trials and into your nearest pharmacy shelf.

Until recently, patients only showed up in this process as volunteers for the clinical trials and as the final customer once the drug reached the market.

I’ve trained as a scientist, one of those that first discover things in the lab, but for the last 7 years I have been working with patient organizations. I have been able to witness (and join!) a true revolution in the way we discover medicines, with patients and patient groups taking a leading role from the very beginning. The field of rare diseases, where each disease affects only hundreds or thousands of patients world-wide, is leading this revolution. Their diseases were once orphan to medicine, too rare to receive sufficient attention and investment to move the needle. Today patients take ownership of their research fields, and move the needle themselves. They have become the center of the network and the expert in the room. They are impatient, not wanting to wait for pharma to take an interest in their disease. They are impatient patients and are leading an impatient revolution.

A keyword that has become mainstream in these recent years is “patient engagement”, with companies wanting to reach out to patient groups but not sure of what patient engagement would actually involve, what best practices apply, or how they can measure the value of those interactions. The industry is following the patients in this revolution, and learning from them.

I published a free eBook in February of 2017 called the #ImpatientRevolution that summarizes much of my learnings as a scientist working with rare disease patient organizations. It is written with the impatient patients in mind, and talks about how drug discovery works, what they can do to advance research from a patient organization, and how they can engage with the pharmaceutical industry. That´s right, there is much to say about “corporate engagement” as well.

Over the past two years I’ve found myself in many conversations with groups of patients and caregivers that were just starting an organization and wanted to know the best way to do that. The eBook has been a very useful reference in all of these cases, but there is more content and more topics that are not necessarily fully covered in #ImpatientRevolution.

To give me the flexibility to keep adding new content that will serve as a reference for many future conversations, I have decided to start a series of articles called the Impatient Series, and publish them here under Dracaena Report.

Some of the topics I want to include are:

What patient organizations mean when they say they are doing research (different formats that I’ve seen, when to choose one or another)

What patient organizations can do to advance preclinical research, even before the pharma industry gets interested in their disease.

How to make research funding decisions (different formats, when to choose one or another)

How to evaluate and track projects to make sure your money is well-spent.

What makes pharma companies choose one disease vs another one.

What are the types of drugs that could treat rare diseases and what research is needed for each of them.

Working with the pharma industry: NDAs, trust and more.

I also want to address a tricky topic that often comes up when a new patient group finds me and asks me for advice. Their questions are usually followed by “can we hire you to guide our research efforts?” and my answer is invariable no, I can give you some strategic advice but you need to find someone else (I´m only one person with 24 hours in each day). This is usually followed by “where can I find another scientist that could work with us?” and I don’t have an easy answer for that. We are not talking about your usual scientific advisor that remains comfortably seated in their academic chair, but about finding a scientist with the knowledge and entrepreneurial instinct that patient groups need and who is willing to roll up their sleeves and step inside the world of patient organizations.

But I think there is a solution for this because in the last 12 months I’ve started to also come across the reverse situation, scientists who approach me to ask if I think working for a patient group would be good for them and how to find a good patient group. So I am very excited to be adding some new topics to these series that were never covered in the original #ImpatientRevolution Book:

How do I find a scientist that could work with our patient organization.

For scientists: what to consider if you think you might want to work with a patient organization.

…and more related questions to come

As a final note, it goes without saying that this is all personal advice and insights based on my very own experience. I look at the evolving landscape of social entrepreneurship in the patient community, followed by adaptation in the pharma industry worried to be left behind, and try to understand the model that explains it and the rules that it follows. Your experience might be different, and I would love to hear from you. Overall I hope the series will become both a useful resource and a door to dialogue.

Let’s start an #ImpatientRevolution!

Ana Mingorance, PhD

IMPATIENT SERIES ARTICLES:

#1 – WHAT PATIENT ORGANIZATIONS MEAN WHEN THEY SAY THEY ARE DOING RESEARCH

#2 – WHAT ARE COMPANIES LOOKING FOR WHEN CHOOSING A RARE DISEASE

Main lessons from the European Congress on Epilepsy 2018

Every other year the International League Against Epilepsy organises a major epilepsy medical congress in Europe called the European Congress on Epilepsy (ECE). This year I attended the main three days of the ECE addition in Vienna, looking at the field partly as a drug developer and partly as a patient advocate working on behalf of rare epilepsy patient communities. Here is the list of what I found the most interesting at the ECE 2018 meeting.

Every other year the International League Against Epilepsy organises a major epilepsy medical congress in Europe called the European Congress on Epilepsy (ECE). This year I attended the main three days of the ECE addition in Vienna, looking at the field partly as a drug developer and partly as a patient advocate working on behalf of rare epilepsy patient communities.

Here is the list of what I found the most interesting at the ECE 2018 meeting:

1. The big players are gone, the orphan players are taking over.

I missed seeing the large stands in the exhibition hall that UCB or GSK would always have. Instead we are now surrounded by (often) smaller companies that are launching molecules to treat orphan forms of epilepsy. It is an evolution that we also see in other disease fields, and that started becoming clear in epilepsy a couple of years ago. As rare diseases become more popular for drug development and we have more approvals, not only we see more orphan drugs at epilepsy conventions but we also see different players.

If you turned around at the ECE 2018 meeting you could see the stands of GW Pharmaceuticals, fresh from their FDA approval for Epidiolex for treating Dravet and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (expected EMA decision 1H 2019); Biomarin, which develops Brineura, with a stand focused on CLN2 (one of Batten disease types); Biocodex, with the newly FDA-approved stiripentol for treating Dravet syndrome (approved in EU since 2007); and Novartis with a stand on Tuberous Sclerosis Complex for their also recent approval of Votubia/Afinitor.

In addition to those, Zogenix, in very late stages of development of fenfluramine for the treatment of Dravet syndrome, didn’t have a stand but sponsored a symposium on Dravet and had multiple posters. I would expect to see Zogenix and potentially Ovid Therapeutics get some more visibility at the next American Epilepsy Society meeting given their active late-stage programs in Dravet and Lennox-Gastaut syndromes. But for now, at the European meeting, we could already see four orphan epilepsy syndromes replacing much of the exhibition floor space formerly dedicated to medicines with a much broader spectrum. Since I focus on rare epilepsy syndromes, seeing that many drugs coming to the market and so much research on rare syndromes with epilepsy makes me very happy.

2. Epileptologists discussing much more than just epilepsy.

Probably as a combination of paying more attention to rare epilepsies, which often have many serious and disabling comorbidities, and to patient-centricity and patient-empowerment becoming more mainstream, the epilepsy specialists start talking about these epilepsies in a much boarder way which captures much better the patient and caregiver experience. While years ago most presentations would focus on seizures, at the ECE 2018 we also talked about how to explain families a new diagnosis, the impact on caregivers of having a child with a rare epilepsy, the impact on siblings as well, and many aspects related to intellectual disability or psychiatric comorbidities. This large conversation shift was very refreshing for those coming from the patient side, and is likely to lead to much better patient outcomes.

3. A lot of exciting new therapies are coming, in particular for genetic forms of epilepsy.

Many presentations on the future of epilepsy treatments highlighted the new trials that are coming, most focused on orphan forms of epilepsy. In addition to Epidiolex and fenfluramine (for Dravet and Lennox-Gastaut syndromes) several presentations highlighted ganaxolone from Marinus for treating CDKL5 deficiency disorder, XEN1101 from Xenon for KCNQ2 encephalopathy, and OV935/TAK935 from Ovid Therapeutics and Takeda for multiple rare epilepsies as well.

There are also hopes about future genetic therapies able to increase expression from the heathy gene copy, in all of those cases where the disease is caused by a de novomutation in one of the gene copies. In fact, I had the pleasure to meet with one executive of Stoke Therapeutics attending the conference and hear about their program to use an antisense treatment in Dravet syndrome that will increase the missing protein expression. They are still at a preclinical stage, but from my conversation I came out of the meeting convinced that they are doing an excellent work and that they are well-prepared to take into clinical trials, in some years, what could be the first disease-modifying treatment for Dravet syndrome.

I missed hearing a bit more about gene therapy approaches, which we know are also in development for several of these rare epilepsies where the genetic problem is due to a loss-of-function or a loss-of-expression of a gene. I´m sure it won't be long before these therapies are discussed at epilepsy meetings alongside more classical pharmacological approaches.

4. It is never too late to improve the life of a patient living with a severe epilepsy.

As we talk about those potentially disease-modifying treatments, and at the very least disease-targeting treatments, one hope and one fear emerge. The hope is that they will help us treat not only the epilepsy but also the cognitive, psychiatric, motor and other problems that the patient experiences, since they will target the root of the disease. The fear is that beyond certain age, they might do little for the patient.

I have to thank Prof Sanjay Sisodiya from UCL who works with adults with difficult-to-treat epilepsies for his beautiful and inspiring presentation on diagnosing genetic epilepsies in adult patients. He showed us the image of the medical records of a patient with drug-refractory epilepsy and intellectual disability in his late 50s that was the size of an encyclopaedia collection. Going through that much medical history to try to diagnose the patient would represent an enormous challenge to any physician. The patient’s disease was so severe that he had even stopped talking, so one might think that knowing the specific cause wouldn’t make much of a difference to this patient condition. It turns out the patient had Dravet syndrome, which could be identified in a genetic test, and this finding enabled his doctors to remove the contraindicated medication that he was taking and prescribe instead the standard of care for this particular syndrome. The patient condition improved to the point that Prof Sisodiya showed us a video of the patient, now 66, having a conversation with him.

“It is never too late” was the message to the audience.

It is never too late to diagnose a condition, and it is never too late to offer the patient the best medication that is currently available for their disease. This will be particularly important once we have actual disease-targeting therapies in the market, and only then will we be able to know how much improvement is achieved at each age.

SUMMARY

Overall, an evolution of epilepsy therapy discovery from treating symptoms to treating causes is clear. Much of this is driven by improved understanding of the genetic causes of many types of epilepsy, which points to potential new targets for therapies, and much is driven by the progresses in technologies such as the development of more specific ion channel modulators or antisense strategies that now enable us to tackle those targets.

The second major evolution, linked to the previous one, is a greater focus on rare (orphan) epilepsies over the large symptomatic market. This evolution, as is other disease fields, follows a combination of business advantages and better therapeutic fit, given that many of the rare epilepsies have a genetic cause. For example, as one of the most common genetic forms of epilepsy, Dravet syndrome is likely to be the first --or one of the first-- syndromes to get a disease-modifying treatment using these new approaches.

And last, I have seen another evolution in the way that epileptologists talk about the epilepsies at their major conferences, which has become more holistic and patient-centric. When I started working in the epilepsy therapeutics field 9 years ago, the view of epilepsy by the epilepsy specialists and the pharmaceutical companies was much more focused on the seizures and less on the overall patient experience. Now, as a result of much patient advocacy, physicians look at the disease the same way the patient and their families do. Companies and regulators have also changed the way they used to operate, now including much more directly the patient perspective as part of their work, which has expanded the way they see the disease and think about treatments. And in a medical conference like the ECE 2018, this change was very visible.

I personally missed hearing more about CDKL5 deficiency disorder and other “less popular” rare epilepsies, and about some of the non-pharmacological therapeutics in development, such as antisense therapies and gene therapy approaches. Next stop for the epilepsy community is the American Epilepsy Society meeting starting November 30thin New Orleans where I hope to hear more about those topics, and report back.

Ana Mingorance, PhD

En Español - Fármacos en camino para el síndrome de Dravet

Dravet syndrome pipeline review 2018 - Summary in Spanish for Dravet families.

Los avances en torno al tratamiento del síndrome de Dravet en los últimos años han seguido pasos agigantados. En los últimos 5 años hemos experimentado una explosión en el número de programas en desarrollo para tratar la enfermedad: de tener solo Diacomit y nada más a tener Diacomit y 14 más en desarrollo. Este texto es un resumen en Español del Dravet syndrome pipeline review 2018 dirigido a familias, con el texto no solo traducido sino también ajustado a los intereses de aquellos que tienen un hijo/a con síndrome de Dravet y su entorno.

¿Sabíais que hay 14 terapias en desarrollo para tratar el síndrome de Dravet? ¿y que varias de las terapias no buscan solo controlar las crisis epilépticas sino corregir el defecto genético que causa la enfermedad?

Los avances en torno al tratamiento del síndrome de Dravet en los últimos años han seguido pasos agigantados. En los últimos 5 años hemos experimentado una explosión en el número de programas en desarrollo para tratar la enfermedad: de tener solo Diacomit y nada más a tener Diacomit y 14 más en desarrollo.

Por segundo año publicamos una revisión de los fármacos en desarrollo para tratar el síndrome de Dravet (ver entrada).

El texto original va dirigido a empresas interesadas en el sector o que ya están desarrollando fármacos, así como otros profesionales relacionados con la industria farmacéutica. Este año hemos querido ofrecer también un resumen en Español dirigido a familias, con el texto no solo traducido sino también ajustado a los intereses de aquellos que tienen un hijo/a con síndrome de Dravet y su entorno. Hemos incluido texto y una figura adicional dirigido a esta audiencia, y eliminado secciones que no son tan relevantes.

El texto describe todos los fármacos en desarrollo para tratar el síndrome de Dravet a fecha de julio de 2018 y plantea las direcciones futuras.

Esta adaptación de cómo están todos los fármacos en desarrollo para el síndrome de Dravet la dedicamos a los guerreros de la Fundación Síndrome de Dravet, que han contribuido de manera directa a muchos de los logros que resumimos en la revisión.

Un sueño... una meta.

DRAVET SYNDROME DRUG DEVELOPMENT PIPELINE REVIEW 2018

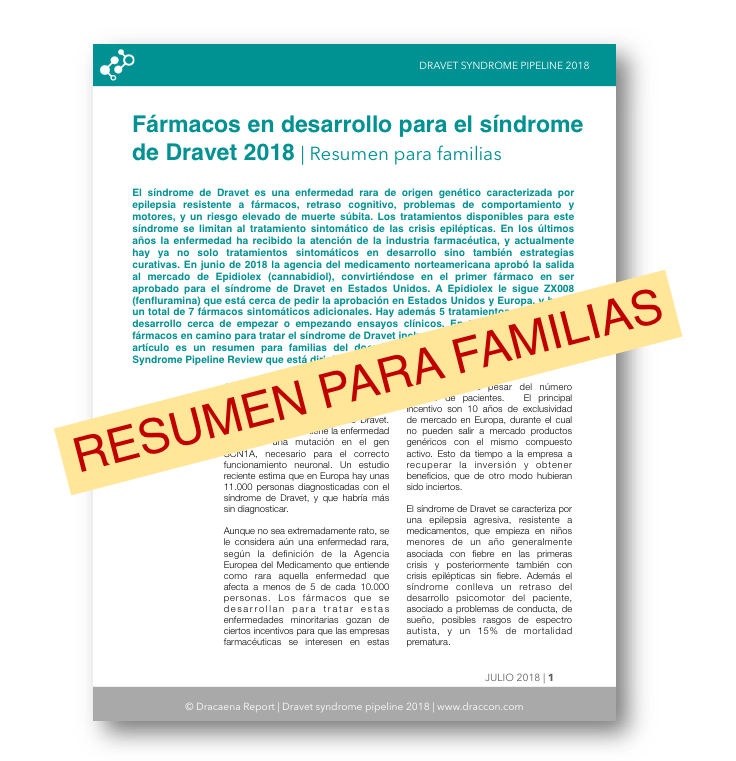

The 2018 Dravet Syndrome Pipeline and Opportunities Review provides a review and analysis of 14 drug candidates in development for the treatment of Dravet syndrome, including 9 products that have received orphan drug designations. It also includes an analysis of the competitive landscape and evaluates current and future opportunities of the Dravet syndrome market.

It has been a year since we released the 2017 Dravet Syndrome Pipeline and Opportunities Review, a market research publication that provides an overview of the global therapeutic landscape of Dravet syndrome.

There have been many developments in the last year, including the approval by the FDA of Epidiolex (cannabidiol) by GW Pharmaceuticals for the treatment of Dravet syndrome, the announcement of positive data from two Phase III clinical trials with ZX008 from Zogenix, and the arrival of a new company pursuing a disease-modifying antisense-based approach (Stoke Therapeutics).

The 2018 Dravet Syndrome Pipeline and Opportunities Review provides a review and analysis of 14 drug candidates in development for the treatment of Dravet syndrome, including 9 products that have received orphan drug designations.

The report includes the most recent updates on Epidiolex (cannabidiol) from GW Pharmaceuticals; ZX008 (fenfluramine) from Zogenix; Translarna (ataluren) from PTC Therapeutics; OV935 (TAK-935) from Ovid Therapeutics and Takeda; EPX-100, EPX-200 and EPX-300 from Epygenix Therapeutics; ZYN002 (transdermal cannabidiol) from Zynerba Pharmaceuticals, BIS-001 (huperzine) from Biscayne Neurotherapeutics; PRAX-330 from Praxis Precision Medicines; SAGE-324 from Sage Therapeutics; OPK88001 from OPKO Health; XEN901 from Xenon Pharmaceuticals; and an ASO program from Stoke Therapeutics.

The 2018 Dravet Syndrome Pipeline and Opportunities Review also includes an analysis of the competitive landscape and evaluates current and future opportunities of the Dravet syndrome market.

The report is now available in this site.

Ana Mingorance PhD

What you should know about patient data after May 2018

After May 2018 patients will have the right to request access to their data files. They will have the right to withdraw their data from a database that is not being used in the way that the patient through it would operate. And they will have the right to obtain these files generated by a particular data holder, for example a gene testing lab, and get the usable file and share it with as many studies and registries as the patient wants. The EU General Data Protection Regulation gives patients the Right to Access, the Right to be Forgotten, and the Data Portability right.

When scientists don’t fight over funding they fight over data.

Having large amounts of data that competitors can’t access means having the upper hand when it comes to publishing and getting funding. Corporations operate the same way. Science is, after all, a knowledge economy, where data is knowledge and knowledge is power.

But in a world where data is seen as an asset, patient rights when it comes to accessing their own data and deciding what to do with it can be compromised. And they are, in a regular basis.

I am a vocal advocate for empowering patients (and individuals in general) by giving them access to their personal data files so that they can know what these contain and choose whom to share it with. I also know that not everybody feels the same way. I have had the opportunity to address data scientists twice, first in 2015 and more recently at a personalized medicine meeting in 2017, and both times I managed to divide the audience and offend some data scientists and clinicians.

The good news is that this debate is becoming obsolete in May 25th 2018, when a new regulation protecting patients right to access their data will enter in force.

The surprising news is that the solution didn’t come from a medical organization but from the EU Parliament, in the form of a General Data Protection Regulation. The key word here is “general”, because the new regulation was not written with patients or even with medical data in mind. It applies to anyone who collects other people’s data. From Google storing your preferences, to Facebook knowing your friends, to your aunt having a mailing list for her cooking blog. And patients are, surprisingly, a key collateral beneficiary of this regulation.

Let me review the current problems that patients face to access their own data and why the General Data Protection Regulation is so important.

CURRENT PROBLEMS AROUND PATIENT DATA

Before 1973 your doctor didn’t need to tell you what he thought was your diagnose, or to ask you to consent to the treatment he was prescribing. This would be unthinkable in today’s world, but it was grounded on the observation that the doctor, and not the patient, is the most knowledgeable person in the room when it comes to medicine. While this is generally true, it is also paternalistic and condescending, and in 1973 the American Hospital Association adopted the Patient’s Bill of Rights to put an end to this practice. After the Bill, patients were entitled to receive information about their disease and to make decisions about treatments (except in emergencies), among other important rights. Similar regulations were then adopted worldwide.

When I give presentations on this topic I like to use the slide below to illustrate the problem of scientists and healthcare providers not supporting the transfer of patient data from a study to another. It shows the example of a patient having to repeatedly give the same personal and medical information over and over to their hospital, a patient registry for their disease, to a couple of academic studies, and probably also to a clinical trial where the patient participates and that is also generating a separate patient registry. The burden on that individual patient is ridiculous, and this is not a made up example. I know multiple cases of patients with rare diseases where they end up interacting with such a large number of data holders in an attempt to get the best medical care and to help advance the scientific understanding of their disease.

There are two separate problems here:

1- Data holders refuse to share the patient data with other data holders.

The main argument is often that the informed consent didn’t consider sharing data with third parties, but in my experience even if the patient (or caregiver) offers to sign a new informed consent to support that transfer the original data holder refuses. As I see it they are not thinking on the patient’s best interest but looking at the data instead as an asset that they own.

2- They also often refuse to share the patient data with the patient himself.

If patients had access to their entire medical history and relevant studies in a way that can be easily transferred to other data holders, such as new registries and studies, the patient would choose who has it and who doesn’t. But they don’t have that choice when they don’t have their data files. The expressed reasons to not grant the patient access to his or her own data files fall often into two categories. One is the technical one, like in the real example: “we never designed our registry with a output format that could be useful to you”. The second is the same one that led to the 1973 Patient’s Bill of Rights, as in another real example: “no we can’t give you your whole exome sequence because you don’t understand genetics, interpreting sequences is hard and confusing, and you might make the wrong decisions based on uninterpretable data”.

The cry of patients for accessing their own genetic sequence data files is so loud that in 2015 the European Society of Human Genetics issued a press release with the following headline: “People want access to their own genomic data, even when uninterpretable”.

It wasn’t about patients having the knowledge to read a raw whole exome sequence file, but about being entitled to get a copy of such file.

I personally thought it would have to be an organization like the European Society of Human Genetics or the American Hospital Association who would issue a new recommendation (or hopefully something more enforceable) to protect patients right to access their own medical data files. Surprisingly the regulation that would come to protect these patients rights was simply a new general regulation for personal data protection that was never developed thinking specifically of patients.

WHAT THE GDPR ACHIEVES

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was approved by the EU Parliament in 2016 and will enter in force in May this year. It doesn’t matter where the organization that collects personal data of data subjects (including medical data) is located. What matters is that if the data subject resides in the EU, the organization needs to be compliant or face heavy fines. Unless organizations are planning to follow separate Standard Operating Procedures for EU and non-EU residents, most will simply have to be compliant with the GDPR and the new regulation will also protect non-EU patients.

My favorite “data subject rights” are the following:

1- Right to Access.

Under the GDPR the data holder will have to provide patients with a copy of their personal data, free of charge and in a machine-readable format. It won’t be ok to argue that the database wasn’t built for export functions or to be passive-aggressive and give the patient only a small summary in a PDF. The patients, and all data subjects in general, are now empowered to have a copy of their data files, to know how much data the data holder has collected from them, and to know what they are using it for.

2- Right to be Forgotten.

Under the GDPR the data holder can withdraw consent and request their data to be removed from the data holder files and to not be user or disseminated. If you are a patient that gave data to a registry on the understanding that they would use it to further research in your disease, and you later become aware that they are refusing to share data with other research groups, you can now approach the registry and request your data to be removed.

3- Data Portability.

Under the GDPR the patient can request the data holder to provide them with a copy of their files in a machine-readable and usable format not only for their own records, but also to transfer them to another data holder. In my real example of a rare disease patient that has his data in multiple registries and studies, the patient can now get usable files from his hospital including proper gene sequencing files and then share this file with the other registries and studies. They won’t have to give the same data, and be subject to the same procedures, over and over as it happens nowadays.

AFTER MAY 2018

After May 2018 I will have to change my PowerPoint presentations. Patients will have the right to request access to their data files. They will have the right to withdraw their data from a database that is not being used in the way that the patient through it would operate. And the patient has the right to obtain these files generated by a particular data holder, for example a gene testing lab, and get the usable file and share it with as many studies and registries as the patient wants.

In 2015 I offended some data scientists at a big data meeting with the following message:

“Health data must be shared

In particular with the patient (even if they don’t understand it)

Because it is their data

And because they will share it”

I wanted to shift the conversation on giving patients’ access to their own data from “the patients don’t understand the data” to “they need to have access so that they are able to share their data”. I guess we don’t need to debate this anymore. After May 2018 we just need to say that it is the new law!

Ana Mingorance PhD

Big gene, small virus

There is no doubt that AAVs will support the development of many gene therapies for genetic diseases, but for many diseases AAVs are too small to carry a copy of the gene that patients need. There is a strong need to find non-AAV alternatives that can provide a suitable gene therapy option for those diseases caused by mutations in large genes. Within Dravet syndrome, these next-generation therapies are being led not by companies but by academic groups with the support of patient organizations. This is a review of these programs and how they are attempting to develop a gene therapy for treating Dravet syndrome.

We wrapped up 2017 with the news of the first gene therapy approved in the US to treat a genetic disease. It was Luxturna, approved for treating vision loss in patients carrying mutations in a particular gene that causes retinal dystrophy. The videos of vision improvement in patients treated with Luxturna that Spark Therapeutics has shown are breathtaking, and I trust gene therapy will one day be the go-to treatment for most genetic diseases.

There are in fact many genetic diseases! From the estimated 6000 to 8000 rare diseases, the large majority is thought to be also caused by gene mutations. And the most common consequence of those mutations is loss of function of the gene, so the approach that Luxturna used to deliver a backup healthy copy of the gene to the affected cells would be the ideal one.

But here is the catch: Luxturna uses a small virus, called Adeno-Associated Virus or AAV, to deliver the therapeutic gene to the affected cells. AAV is the gold-standard when it comes to gene therapies in development, with many advantages over other virus that are less infective (don’t get into as many cells) or might trigger an immune response. But AAV can only transport small genes, and not all diseases have mutations in small genes.

In a recent Dravet syndrome families meeting, a gene therapy expert explained to the parents that that scientists have been very good at developing cars able to transport a healthy gene copy to the patient, but that their particular disease will need a bus. I like the metaphor very much.

Many diseases will need virus larger than AAV to be able to have a gene therapy. We need a bus.

CAN WE MAKE GENES SHORTER?

In some diseases that have “big genes” it might be possible to develop shorter versions of the gene that could fit into an AAV and retain sufficient functionality to have therapeutic benefit. The main example that comes to mind is the mini-dystrophin gene, which is currently in clinical trials (here and here). This approach is only possible because dystrophin is a large scaffold protein that needs to attach to multiple partners and can be reduced to only those main protein domains retaining functionality.

Dravet syndrome is caused by mutations in the SCN1A gene, which produces an ion channel that needs to cross the plasma membrane 24 times. Such a large protein needs to go in an out the membrane the right number of times and to have the right loops inside and outside to be able to form the correct channel structure and functionality. There is no spare protein bit that we could chop out of the gene to reduce it to a size where it could fit into an AAV. We need a bus.