Epilepsy Insights

Top 5 insights from the American Epilepsy Society meeting (2018)

Every year the American Epilepsy Society (AES) meeting gets larger. This year, over 6,000 people gathered in New Orleans to discuss the latest information about epilepsy care and the development of new treatments for epilepsy. The 2018 meeting captured the latest developments in the field of epilepsy drug development, where rare disease populations and new technologies are two areas of considerable growth and that are changing the way we will treat epilepsy. This article highlights what I found the most interesting at the AES 2018 meeting.

Every year the American Epilepsy Society (AES) meeting gets larger. This year, over 6,000 people gathered in New Orleans to discuss the latest information about epilepsy care and the development of new treatments for epilepsy.

I look for therapies for rare genetic epilepsies, so this biases some of my focus during the meeting. At the same time, many of the biggest developments have been precisely in the field of rare epilepsies, so this has been a very exciting year.

Here is the list of what I found the most interesting at the AES 2018 meeting:

1- Many new epilepsy drugs are orphan drugs

Probably the star of the AES 2018 meeting was GW Pharmaceuticals, operating in the US as Greenwich Biosciences, with Epidiolex (cannabidiol oral solution) now in the market for the treatment of epilepsy in Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome in the US. Greenwich had a very large presence at the meeting, with a prominent spot in the exhibition hall and the most crowded scientific exhibit. There was also a very popular session on the perspectives of physicians and patients about using cannabidiol for the treatment of epilepsy, which highlighted the interest of the patient and medical community on Epidiolex.

But there is more interest in the orphan epilepsy space than just Epidiolex. Next to Greenwich at the exhibition hall we could see Zogenix, with Fintepla (fenfuramine) about to file for an NDA for the treatment of epilepsy in Dravet syndrome, and BioMarin with Brineura (cerliponase alfa) for CLN2 disease, a type of Batten disease.

There were also other orphan epilepsy players that didn’t have a stand at the exhibition hall but had important presence at the AES meeting, most notably Marinus Pharmaceuticals which is currently in Phase 3 trials in CDKL5 Deficiency Disorder (CDD) with ganaxolone. Marinus had multiple poster and platform presentations, and a very well-attended scientific exhibit, showing early clinical data as well as biomarker data in CDD and PCDH19, to orphan epilepsy syndromes.

2- From symptoms to disease: epilepsy goes beyond pharmacology

There was one key progress visible at the AES 2018 meeting that defines a before and after moment in the field of epilepsy, and this is the arrival of non-pharmacological therapies for treating epilepsy.

Until now, we have seen progresses in many genetic epilepsies, using approaches such as enzyme replacement, antisense treatment or AAV-based gene therapy. But these were still not so visible in epilepsy, with the exception of Brineura for CLN2 disease which could be considered a neurodegenerative disease with epilepsy, more than an epilepsy syndrome. This year at AES 2018, however, we could see a broad range of disease-modifying experimental therapies in preclinical development for the treatment of different forms of epilepsy that are likely to lead to clinical trials using antisense approaches or viral gene delivery within two to three years:

Stoke Therapeutics presented some early but very impressive preclinical proof-of-concept data for their antisense oligonucleotide treatment for Dravet syndrome. The antisense treatment results in an increase in the Nav1.1 protein, and the company plans to initiate clinical trials in 2020 (see poster).

RogCon Biosciences and Ionis presented data on an antisense oligonucleotide treatment, this time for SCN2A epilepsy linked to gain-of-function mutations. The antisense treatment results in a decrease in the Nav1.2 protein and they showed efficacy in a mouse model (see poster).

A team by the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland presented a very interesting approach, where they used antagomirs (which are also antisense oligonucleotides) to reduce the activity of miR-134 in a mouse model of epilepsy, leading to strong long-lasting seizure suppression. Interestingly, this approach would not be just targeted to a specific genetic epilepsy but might represent an alternative to pharmacological treatments or brain surgery for treating refractory epilepsy resulting from multiple (including unknown) causes.

A team from the Columbia University Medical Center also presented an approach for using viral delivery of a specific micro-RNA against the gene DNM1. This gene is mutated in an epilepsy syndrome, and the mutant alleles act have dominant negative properties. The approach, piloted in a mouse model of DNM1-dependent epileptic encephalopathy, improved multiple disease phenotypes.

Another surprise at the AES meeting was the first appearance of Encoded Genomics, still in stealth mode, as the sponsor of the Dravet Syndrome Roundtable. The Encoded team explained that the company is developing a gene therapy for Dravet syndrome, although no more details have been communicated at this point.

And although still using small molecules, Praxis Precision Medicine (1,2,3) and Xenon Pharma (1,2,3,4,5,6) also presented very interesting data of their Phase 1 programs to target specific genetic epilepsies caused by mutations in sodium and potassium channels, although they also have potential beyond these orphan epilepsies.

The number of programs in development using these new technologies, as well as the involvement of private companies in these programs, is unprecedented for the epilepsy field and make 2018 as the year when the new therapeutic approaches took a first important step in the epilepsy field. Within a few years we should see multiple of these disease-targeting programs in clinical trials.

3- Multiple great treatments for Dravet syndrome

Following the diagnosis of a child with a rare genetic disease, often families are told that the industry is not interested in developing treatments for them and that there is little research or that their disease is barely understood. This is definitely not the case for patients with Dravet syndrome.

There were 65 presentations on Dravet syndrome at the AES 2018 conference, and the syndrome is the target indication for some of the most promising pharmacological approaches in development as well as soon to reach the clinic disease-targeting approaches:

Epidiolex (cannabidiol oral solution) just got approved in 2018 in the US for treating epilepsy in Dravet syndrome (European decision expected in early 2019).

Fintepla (fenfluramine), from Zogenix, has completed two successful Phase 3 trials in Dravet syndrome with very impressive efficacy, and the main question mark around this dru,g which was a potential cardiac safety concern, has so far proven to be not a problem in this patient population. Fintepla is on track to be the next drug approved for treating this syndrome.

Ovid Therapeutics and Takedaare partnering around the development of TAK-935, a novel antiepileptic drug, which is also in clinical trials for Dravet syndrome. There were a poster and a talk on the preclinical proof-of-concept for this drug in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome and the data was extremely solid, with impressive efficacy in preventing spontaneous seizures and early mortality in the mice. So as impressive as Fintepla is in this population, TAK-935 might be a fair contender with a differentiated mechanism of action. Both therapies are also in clinical trials for Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

Stoke Therapeutics follows the Ovid and Takeda collaboration in the pursuit of Dravet syndrome as the target indication for their lead antisense program, and also showed very good early data in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome at AES 2018. Their therapy will be the first disease-modifying approach to reach the clinic for Dravet syndrome after multiple pharmacological trials.

And as we wait for more information about the program, the gene therapy for Dravet syndrome in development by Encoded Genomics might follow Stoke’s antisense therapy into the clinic, completing a very promising pipeline of treatments in development for a single orphan epilepsy.

Possibly as a reflection of this increased industry interest in Dravet syndrome, the Epilepsy Therapy Screening Program run by the NINDS mainly at the University of Utah now offers a test in a genetic mouse model of Dravet syndrome that was also presented at AES 2018.

4- Near-approval treatments for acute repetitive seizures

There are some important progresses towards the management of acute repetitive seizures (cluster seizures) that were presented at AES 2018 and are worth highlighting.

A study presented at the conference highlighted that clusters (more than one seizure within 6 hours) were present in about half of pediatric patients with active epilepsy. Seizure clusters are common in many refractory epilepsy syndromes, and they are managed by using rescue (acute) medication. Rectal diazepam is the most widely use rescue medication for seizure clusters, but there is a strong demand from the patient community to develop alternatives. There are now two programs that would provide a suitable alternative and that were presented at AES 2018: intranasal diazepam (NRL-1, by Neurelis), and intranasal midazolam (USL261, by UCB Pharma). Both programs are expected to obtain the marketing authorization soon by the FDA. Their future in the European market is less clear given that the EMA has not yet accepted acute repetitive seizures as a separate orphan indication, which is the status of these experimental therapeutics at the FDA.

I also found interesting the description of a novel mouse model of acute repetitive seizures, which will support the development of new drugs beyond the currently used benzodiazepines.

Last, a young company called Engage Therapeutics is pursuing a very innovative EpiPen-like approach to try to abort seizures using a hand-held inhaler for fast systemic delivery of alprazolam. They announced at AES 2018 that they are starting a double-blind placebo controlled study.

5- AES is also a big meeting for patient organizations

A growing number of rare epilepsy patient organizations are using the AES annual meeting to host focused meetings with their main clinicians and scientists as well as with the companies developing therapies for that disease (or interested in doing so). Some of the veterans are the Dravet Syndrome Foundation and the Lennox-Gastaut Foundation, but we are also seeing more and more of the smaller groups, some of them in the first or second year of activity, also using AES to bring into a room the different stakeholders that are going to help them develop new treatments. In these focused meetings patient representatives and industry break their distances and learn from each other, becoming very educational and productive meetings.

Patient organizations were also present at the exhibit hall, and this year I counted 19 different groups.

Last, I really liked starting to see patient advocates take the stage as part of the main conference program. For example, I enjoyed listening to Dr Tracey Dixon-Salazar from the Lennox-Gastaut Foundation share the stage with some of the main neurologists who have run the Epidiolex clinical trials. In this type of medical conference, we should always ask ourselves: “medical specialists are telling us that this new drug has a favorable risk/benefit profile, but what do the patients think about it?”.

Summary

I had closed my review of the European Congress on Epilepsy (August 2018, Vienna) saying that “I personally missed hearing more about CDKL5 deficiency disorder and other “less popular” rare epilepsies, and about some of the non-pharmacological therapeutics in development, such as antisense therapies and gene therapy approaches.”

Looking back at those comments I’m glad to have seen more presentations about less popular rare epilepsies, including the multiple presentations by marinus on CDKL5 Deficiency Disorder, as well as the many disease-targeting approaches that I listed under section 2. In that sense I feel that the AES 2018 meeting captured better the actual developments in the field of epilepsy drug development, where rare disease populations and new technologies are two areas of considerable growth and that are changing the way we will treat epilepsy.

I can’t wait to see what 2019 has to bring!

Ana Mingorance, PhD

IMPATIENT SERIES #5 – EVALUATING AND TRACKING PROJECTS

When you let the scientific community know that your organization is open to fund research around your rare disease you are likely to get many research proposals from academic groups. These will come in different qualities, and will have different relevancefor your disease. This entry adds to Impatient Series I and to the ImpatientRevolution book and discusses in more detail how to determine that a proposed project is the right one and how to monitor its progress.

In the first entry of the Impatient Series I discussed what patient organizations mean when they say they are doing research.

This entry adds to Impatient Series I and to the ImpatientRevolution book and discusses in more detail how to determine that a proposed project is the right one and how to monitor its progress.

When you let the scientific community know that your organization is open to fund research around your rare disease you are likely to get many research proposals from academic groups. These will come in different qualities, and will have different relevancefor your disease.

As in the proverbial “if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail”, most groups will try to tell you that the way to address your disease is to apply exactly the same techniques that you are using to your particular disease model. This is not an attempt to mislead you, since they all have chosen to build their laboratories around that specific technology or approach because they believe in it. This is why you need impartial advisors to help you select the best and more relevant applications.

HOW TO JUDGE THE QUALITY

The best way to determine the quality of research proposals is to use some trusted scientists as reviewers. Scientists are used to evaluating other scientists research proposals and manuscripts, it is part of their usual jobs.

Some of the aspects they should pay attention to are: does this group have the expertise that they need for this project? Are the proposing the right controls? Is the amount of work realistic with the proposed duration and funding request?

I also like to ask if this is the best lab that could do this approach, since a group might conclude (perhaps correctly) that the best approach for your disease is to develop a gene therapy and propose to do this in their lab, even though they are not a lab that has done gene therapy before.

HOW TO JUDGE THE RELEVANCE

It doesn’t matter how excellent the research proposals are, if they don’t directly advance your agenda you should not fund them. You did not create a Foundation to compete with the NIH for funding the very best grants, you created it to fill the gaps of your specific disease research field so that therapies can be developed faster.

Because of that your scientific advisors should also be able to evaluate if a given proposal is an interesting area to explore, vs a core bottleneck in the field to address, to cite to extremes.

To make the life of the applicants easier, I recommend that you decide, before opening a call for grants, which are the core interest areas that you are seeking proposals for. The more specific you can be the better. Saying that you are looking for proposals to “advance knowledge of the disease X, translational research or clinical research” would be too vague and of little help. Saying that you are looking for proposals to “identify substrates of kinase X, develop translational biomarkers and to validate new clinical outcome measures” would be much more clear.

Having pre-determined your key interest areas will also help you see if there is one of them for which you are not receiving proposals, in which case you might want to directly reach out to specialists in the area and propose them to work with you to address that need.

HAVING AN INTERNAL TEAM

At this point, if you are a young patient organization or foundation, you might be wondering how to manage the complexity of identifying scientific advisors, sourcing grant proposals, and determining research priorities. As I explained in the Impatient Series I entry, I am a strong advocate for you to consider having a researcher or an internal team, depending on your side, that works for your organization and that can be on top of all this. Having a researcher will also facilitate conversations with the industry and with regulators, since the right researchers will have a background that will make them capable of interacting with those professionals.

Having a scientist that works with you, even if part time, will also be very important for monitoring the progression of the projects that you are funding and making sure these are successful. In the next Impatient Series article I will discuss my thoughts about scientists working inside patient organizations or foundations.

MONITORING PROJECT PROGRESS

For monitoring project progression, I recommend quarterly project reviews (ideally written reports), and a final written report. Unless there is a big milestone coming up soon, requesting updates more often than that is not useful for research. Of course you should always have back and forth of short communications with the labs to make sure they all have what they need to move forward and be able to help with the troubleshooting.

It is a good practice when you follow up with the labs to ask “is there anything we could do to help you with this” whenever the lab expresses some delays or difficulties. This is also why it is useful to have a scientist doing these follow ups.

At the Spanish Dravet Syndrome Foundation we also used to run twice a year portfolio reviews, which were a half a day face-to-face meetings where every funded lab would present their results in the last period. At the Loulou Foundation we do this once a year, also for half a day, the day before our big CDKL5 Forum. The benefit of these meetings is that not only the Foundation gets an update about the projects, but all the different groups in your current portfolio get to see each other’s presentations and every single time that starts sharing and collaborations. I find these meetings very useful.

If you schedule these portfolio reviews right before another important meeting, for example your annual families meeting, and ask the groups to budget for this trip in their grant proposal, you will make it easier for them to also attend your meeting and potentially give an update to the families and other members of the community during the same trip.

At the end of the funding period, the groups should provide you with a financial update, outlining where the money was spent. For quarterly reports I think only a scientific update is needed.

Another important aspect to consider is intellectual property (IP). Some organizations don’t ask for any rights to part of the IP, while some others might ask for too much. I like very much the Loulou Foundation policy of asking for a percentage of the benefits from IP proportional to the funding that was used to create that IP. This empowers us to ask the groups to consider if any part of their discoveries is susceptible for IP creation, for example the method of use of an old drug for treating your disease if that is what they tested in their project. In this specific example, an academic group naive to how drug development works might publish the results without submitting a provisional patent application first, making it impossible for a company to then take that drug into clinical trials for your disease. Having the rights to part of the IP revenue also gives us a seat at the table during technology transfer negotiations, and help us see if the university is making enough efforts to get that IP turned into an actual product or drug program or if they are sitting on it and not making any efforts. To prevent this scenario, you might want to include some clawback provision into your intellectual policy clause which the groups need to sign in order to receive your funding.

Although asking for shared IP rights is attractive, you also have to be realistic. There are very few CureDuchenne. If you can only give small grants, you can’t expect to have shared IP. For example most patient groups I. know can only provide $20-50,000 per project, which is just co-funding the project. One the other hand, many of the Foundations are able to give significantly larger grants, of over $100,000 per year, and stand a more realistic chance of asking to have a percentage of the IP revenue. To know what you can ask, I recommend you seek advice from people familiar with technology transfer who will be able to advice you based on the particularities of your organization.

Last, make sure you request your grantees to notify you of any publications and conference presentations that result from the project that you fund, and that they include your funding in the acknowledgments. This will help you track the results of your funding beyond the duration of the funding period.

The next entry of the Impatient Series will address how to find a scientist to work with your organization.

Let’s start an #ImpatientRevolution!

Ana Mingorance, PhD

Main lessons from the 2018 CDKL5 Forum

For the past four years the Loulou Foundation hosts an annual “by invitation only” meeting where scientists and drug developers working on CDKL5 deficiency, together with representatives from patient organizations, meet to discuss the latest advances. This was the second Forum I attended, and my first since joining the Loulou Foundation.

Here are the main news and take-home messages from the 2018 CDKL5 Forum that took place in London, UK, in October 22 and 23.

For the past four years the Loulou Foundation hosts an annual “by invitation only” meeting where scientists and drug developers working on CDKL5 deficiency, together with representatives from patient organizations, meet to discuss the latest advances. This was the second Forum I attended, and my first since joining the Loulou Foundation.

There were major news announced during the meeting, like a new Phase 2 clinical trial in CDKL5 deficiency disorder with fenfluramine, a drug that has completed two Phase 3 clinical trials in Dravet syndrome with very strong efficacy, and the announcement that Ultragenyx will develop a gene therapy for CDKL5 deficiency disorder.

For those of you who didn’t attend but are interested in the field, here are the main news and take-home messages from the 2018 CDKL5 Forum that took place in London, UK, in October 22 and 23:

1. The development of therapies for CDKL5 deficiency disorder has progressed very fast

One of the CDKL5 researchers explained from the stage that 4 years ago there were only 20 publications on CDKL5. Four years later, he was standing in a room with nearly 200 scientists and drug developers, discussing 4 clinical trials. From what we know today about the pipeline, in 4 more years we might already have the first symptomatic drugs approved, and will be running clinical trials with the enzyme replacement therapy and gene therapy that are already in development. This speed of development in a rare disease is truly remarkable.

The Chief medical Officer of Marinus echoed these comments by reminding the audience that just a year ago they stood in front of the regulators discussing if “CDKL5 deficiency disorder” was truly a disease or simply a gene that can present as many different syndromes when mutated. After the Loulou Foundation and the patient organizations mobilized and made sure that CDKL5 deficiency disorder was listed in the major disease classification websites and documented as the separate entity that it is, the FDA not only accepted the indication but also approved the first pivotal trial for this disease. We went from not having a recognized disorder to getting green light for a pivotal trial in a matter of weeks.

2. There is a strong industry interest in CDKL5 deficiency disorder

In addition to Marinus Therapeutics, which is in the middle of recruiting for their Pivotal stage Phase 3 trial for CDKL5 deficiency disorder, there were 22 more companies in the room at the 2018 CDKL5 Forum. Last year meeting took place in Boston, and 35 companies attended, but I personally through that the majority would only be there because they have local offices and it was easy for anyone who was just mildly curious to drop by. Having 23 companies come to London means the interest goes beyond mere opportunistic curiosity, and that list of programs in development to treat CDKL5 deficiency disorder is likely to grow in the next few years as this interest materializes in development programs.

The Loulou Foundation honored the companies Takeda and Ovid Therapeutics during the Forum in recognition of their contribution to research and therapeutic development in CDKL5 deficiency disorder

The current pipeline for CDKL5 deficiency disorder has one drug in Phase 3 (pivotal) trials, and three drugs in Phase 2 (proof-of-concept) clinical trials:

Phase 3: Ganaxolone, from Marinus Therapeutics, currently enrolling through 40 clinical sites across EU and US. This is the only placebo-controlled pivotal trial requested for registration of the drug, so once completed Marinus should be able to file for marketing authorization. The company estimates to enroll 70 to 100 patients in total.

Phase 2: Ataluren, from PTC Therapeutics, currently completing a placebo-controlled investigator-initiated study at NYU Langone Medical Center in children with CDKL5 deficiency disorder caused by non-sense mutations. This study enrolled 9 patients.

Phase 2: OV935 (TAK-935), from Ovid Therapeutics in partnership with Takeda, currently enrolling for an open-label study through multiple sites in the US a total of 15 patients with CDKL5 deficiency disorder.

Phase 2: Fenfluramine, from Zogenix, soon to start enrolling for an open-label investigator-initiated study at NYU Langone Medical Center in children with CDKL5 deficiency disorder. This study will enroll 10 patients, and was announced for the first time at the CDKL5 Forum.

3. Companies developing cure-like treatments for CDKL5 deficiency disorder are moving forward aggressively

Amicus recently announced a collaboration around a new AAV (gene therapy)-based technology to complement their enzyme-replacement therapy in development for CDKL5 deficiency disorder. With this new approach, they will use a virus to deliver a secretable form of the CDKL5 enzyme to brain of patients, so it can replace the missing endogenous enzyme.

The first day of the 2018 CDKL5 Forum meeting brought the groundbreaking news that Ultragenyx, one of the strongest players in the rare disease space, had reached an agreement with RegenXBio, one of the strongest players in gene therapy development, to develop a gene therapy approach for CDKL5 deficiency disorder.

With the strong interest that this rare disease is attracting, and its potential tractability by enzyme replacement and gene therapy approaches, we are likely to see the number of companies working in this space grow, and hopefully some clinical trials starting in a couple of years.

4. The preclinical knowledge and preclinical toolbox have progressed much

We have progressed much in our understanding of the biology of CDKL5 and the consequences of the deficiency for cells and animals. One of the main breakthroughs of the past year has been the identification of some of the substrates of CDKL5, which were discovered in separate labs using different approaches and are therefore very solid findings. Interestingly, these key phosphorylation targets are cytoskeleton-binding proteins, which appears to be one of the main cellular domains where the kinase is important.

It was also encouraging to see that there are multiple mouse models generated for CDKL5 deficiency disorder, either missing the gene or carrying patient mutations, and that there are some solid phenotypes that are reproducible across labs and that can help carry out preclinical trials in the disorder. Interestingly, these mice don’t develop spontaneous seizures, but with four drugs in clinical trials for the disease using seizures as the primary efficacy endpoint this does not seem to be a problem for the pharmaceutical industry. The consensus in the room was that “a mouse is a mouse” and as long as the mice have clear neurological phenotypes that are driven by the deficiency in CDKL5 they are good models. The most anticipated experiment, the “rescue” experiment where expression of CDKL5 is turned back on in previously deficient mice, is about to start thanks to the creation of a conditional mouse model and the entire field awaits with expectation those results.

5. Getting the field ready for more complex clinical trials

We also discussed during the Forum that although the first clinical trials in CDKL5 deficiency disorder are using seizure frequency as the primary efficacy endpoint, it is expected that future clinicals will measure more broadly the developmental disability of the disease and any potential improvement from treatment. Speakers from Ultragenyx and Roche explained how the industry approaches the development of new clinical outcomes and the importance of precompetitive collaborations in this space to move the field forward. The Loulou Foundation and IFCR (the US CDKL5 deficiency patient organization) are planning to host an externally-led PFDD meeting with the FDA in 2019 that will also assist with the identification of new meaningful clinical outcomes.

A captivating and inspirational Dr Emil Kakkis, from Ultragenyx and the EveryLifeFoundation, shared with the audience his journey to convince the industry that developing therapeutics for rare diseases was worth it, and some of his victories and approaches to turn these aspirations into a reality. He made a call for the use of multi-domain outcomes and biomarkers in clinical trials in rare populations, and why he thinks that the golden age of rare disease treatments is now coming to CDKL5 deficiency disorder.

“These are exciting times for rare diseases, and CDKL5 deficiency disorder is now front and center. Collaboration and cooperation is needed to identify the best outcomes as soon as possible. “

6. There is a strong patient community behind CDKL5 deficiency disorder

The very young CDKL5 Alliance, the umbrella organization that groups 15 patient organizations and foundations, announced during the CDKL5 Forum the launch of their website with the hope of making it easier for any family around the globe to stay updated about progresses in the field and to connect with other patient families (http://www.cdkl5alliance.org).

The CDKL5 Alliance met during the Forum and set some of their next priorities, including the identification of more patients and setting Centers of Excellence in every country so that the community is ready to run multiple clinical trials. They also receive the Champion of Progress 2018 award from the Loulou Foundation for building and keeping the community together.

During the Forum, the patient groups and the Loulou Foundation were credited with having been instrumental to the large progress in the field so far. From providing the key initial funding to research labs, to helping create Centers of Excellence and reaching out to companies to encourage them to consider their disorder and help them. Essentially, the secret for points 1 through 5 in this summary is the strong patient community behind CDKL5 deficiency disorder.

The patient groups and the Loulou Foundation have also managed to createa broader community where scientists and drug developers also find their home. This was particularly visible during the 2018 CDKL5 Forum where drug developers mixed with academic scientists and clinicals as speakers and moderators in the meeting, and where breakout sessions to help design the future of CDKL5 research sat around the table researchers, drug developers and patient parents without distinctions.

All in all this was a really good scientific meeting, with strong collaboration from all sectors in the CDKL5 community, and where it became clear that as Dr Kakkis said CDKL5 deficiency disorder is now front and center, and where we have a real opportunity to change the future of the disease.

Ana Mingorance, PhD

Impatient series #4 – The place for patients in preclinical research

Once there is a drug that has been developed, it is very clear why talking with patients and collaborating with them is useful for pharmaceutical companies. What is less obvious to both companies and patient organizations is how patients can be active in research before there is any drug in development, during the preclinical phase, and how this might lead to medicines being developed. Some patient organizations might start by funding some academic group, but without a clear vision and a longer-term strategy the return on those efforts will be compromised, and medicines will take longer to come. Here I want to outline the broader strategy that patient organizations can follow to advance research towards new medicines even before companies are working on it.

Once there is a drug that has been developed, it is very clear why talking with patients and collaborating with them is useful for pharmaceutical companies. They often learn about the disease from patients, so that they can better understand the symptoms and how to design clinical trials. Patients are also involved at different stages in the regulatory pathway, providing feedback to the regulatory agencies during trial protocol approval, orphan drug designation or marketing authorization.

What is less obvious to both companies and patient organizations is how patients can be active in research before there is any drug in development, during the preclinical phase, and how this might lead to medicines being developed. “Preclinical” refers to the research that is done before a therapy can be tested in patients. Some patient organizations might start by funding some academic group, but without a clear vision and a longer-term strategy the return on those efforts will be compromised, and medicines will take longer to come.

What follows is my advice on how to approach early-stage research for those interested in advancing research from a patient organization. My main advice to patients working on a disease is to “own” the field, don’t leave this up to academic scientists.

To focus on advancing the research field means more than funding a couple of research programs. I list many specific research programs that are important early on in a field in the eBook the #ImpatientRevolution. Here I want to outline the broader strategy that patient organizations can follow to advance research towards new medicines even before companies are working on it.

1) CONNECT

A key value that patient organizations bring to a research field is to create communication channels between the different researchers working on it. This might be formalized, like hosting an annual scientific meeting, or more informal, simply by knowing everyone in the field and introducing them to one another. By creating these connections researchers start collaborating and have improved ability to obtain funding as they bring key collaborators onboard. So no only research will be improved by increased communication, but also this community will be able to mobilize more public funding towards their rare disease by building a stronger scientific base. The way to start these connections can be as simple as reaching out to corresponding authors in PubMed publications related to your rare disease, and by always asking “who else do you recommend me to talk to?”.

2) TOOLS

For scientists to work on a rare disease, or any disease in general, they need to have a tool box. These are research tools, without which scientists cannot build the science. Research tools include animal models of the disease, cell lines (lab cells expressing the disease protein or patient-derived cells), antibodies that recognize the disease protein, or the DNA of the disease gene that is then used to create these models. For anyone to research a rare disease, they are going to need to use these tools.

Because they are so necessary, scientists who are the first to invest the time and resources to create those tools might hold on to them, limiting who else can work in the field. This happens very often in rare diseases, when only one lab has a knockout mouse model for the disease, or has the only good antibody for that protein. Keep in mind that academic science is very competitive, and being the only lab in the world able to do something is highly prized. This creates the incentive of not sharing, and seeing other labs wanting to work on the same disease as competitors.

Don’t let any scientist decide who can or cannot do research in your disease. Build all these tools yourself and make them open-access – or if you finance a lab to build these tools make sure your funding contract makes it mandatory for them to share it with anyone afterwards, for-profit companies included, without being able to veto anyone.

By making sure your rare disease has the complete toolbox available to all scientists you will mobilize a large number of researchers towards your disease. You might also start to attract pharma companies. Reducing the barriers of entry to your field is one of the best things you can do as a patient organization.

3) KEY QUESTIONS

Beyond investing in building the toolbox, you need to identify which are the key questions around your specific rare disease that might also represent a barrier of entry for researchers and pharma companies. It might be that the incidence of the disease is unknown because the first handful of patients has just been described. It might be that the disease is caused by a mutated kinase, and the targets of this kinase are unknown. It might be that the rare disease involves the deletion of a chromosome fragment involving dozens of genes, and the individual gene(s) among all these which is responsible for the disease is unknown. These are all some examples of important questions that are important to solve before therapies can be developed for this disease. If these are still unanswered, as a patient group these should rank very high in your priority list.

I recommend targeting these questions by approaching labs that have already solve this type of questions, even if they are not yet interested in your disease. They are much more likely to be able to complete these projects successfully than labs that you might already be in contact with, who are already familiar with your disease, but who lack the core expertise to ask these questions. You don’t have the time to wait around labs developing new skills, you should try to put together the research tool box and solve the key questions as soon as you can so that a large group of scientists (and potentially pharmaceutical companies) start working on developing therapies for your disease.

4) FAST MEDICINES

Remember the importance of developing the toolbox? One of the early uses of having cell lines and animal models for your rare disease is to be able to find a new drug the fastest way possible: by finding a new use for an old drug.

You will most likely hear early into your journey about drug repurposing. Drug repurposing refers to finding a new use (a new purpose) for an already existing medication, which enables doctors to use it to treat this new disease as well. In some cases there will be clinical trials to seek approval for using that drug in the new disease. In most cases there won’t be clinical trials, and doctors will simply prescribe it off label. In either case as a patient group one of the earliest questions that you should aim to answer is whether there is a drug already out there, sitting at the pharmacy shelf, that could potentially treat your disease. The best way to do this is by using cell lines expressing your disease protein or gene, or by using small animal models such as yeast, c. elegans or zebrafish (the choice depends on the particular rare disease), and use them to run a screen of approved drugs, looking for those able to restore protein function or address a particular disease phenotype. Running a repurposing screen to identify any potential drug that is already available should also very high in your priority list.

A 2.0 version of these efforts is to use those cell lines or animal models to evaluate drugs already in clinical development for related diseases. If you identify a drug with efficacy, the company that is developing it might be interested in expanding those clinical trials to include patients with your disease.

That’s why it is so important to consider all the drugs already developed (or near approval), because if you find a drug that is already approved or in clinical trials and that has efficacy in your disease you will be cutting down by many years, potentially a decade, the wait for new medicines.

5) ENGAGE PHARMA – EVEN AT THE PRECLINICAL STAGE

Last, I still recommend you to try to engage with the biotech and pharma industry as early as you can. Ask them about how they see your disease. Do they see it as similar to another disease? Perhaps similar to a large disease? Do they flag some immediate research gaps? This feedback will help you shape your research strategy as you build a relationship with the industry and learn to think about therapy development.

But these conversations are often not happening, or are not happening early enough. The reasons are multiple on both fronts:

What patient organizations often want when collaborating with companies before there are drugs in clinical trials

Most patient organizations are in touch with companies that have a drug in clinical trials for their disease. Patient organizations that approach companies before these companies have a drug so advanced are often interested in trying to convince the company to work on their disease. Because in most cases this will simply not happen, it is best if the patient groups can switch their focus to learning to understand how industry scientists think about diseases and get their input about their rare disease field. They can also be good door openers if they know people in other companies.

What companies often want when collaborating with patient organizations before there are drugs in clinical trials

At early stages, before they have a drug in development for that disease, industry scientists are interested in learning about a disease beyond what is already published in the medical literature. They want to know what the incidence of the disease is, if there are centers of excellence, and many of the questions I covered in the “when is your disease field ready to attract the interest of companies” article earlier in this Impatient Series.

What holds patient organizations back from collaborating with companies before there are drugs in clinical trials

Patient organizations sometimes refuse to engage with pharmaceutical companies because they believe it creates a (perceived) conflict of interest. They think it is better to remain on the academic science side, and not collaborate with companies. Academic scientists don’t think the same way that industry scientists, and don’t have the same incentives (publications vs drugs approved), so it is a mistake to believe that academic scientists can replace the work and input of industry specialists. My advice is to avoid perceived conflict of interest or biases by simply engaging with every single company in your disease field, without picking favorites, and to make sure they have as many information as they need (see previous section).

What holds drug development companies back from collaborating with patient organizations before there are drugs in clinical trials

People working at pharmaceutical companies usually express the same two fears that keep them away from engaging patient organizations early in the preclinical stage or even before they decide to start a program in a disease. One is disappointing patients. They think that by talking to a patient organization, patients and their families will think that this company will develop a drug for their disease, be successful and reach the market. Industry scientists know that most programs will not even reach clinical trials, so they are worried about disappointing patients. I find it interesting that when I have talked to patients about this they often tell me that talking to companies and knowing that companies are interested in their disease makes them feel more at peace, versus worrying that no one is doing research or developing a drug. Living with a rare disease is hard enough, patient don’t think there is going to be a perfect cure developed overnight, they rather express the need to know that efforts are ongoing and that they are not alone at trying to look for a medicine.

The second main fear that industry employees express is lack of confidentiality. I will want to address this in a future entry in the Impatient Series. It is important for patient organizations to remain professional, and not disclose confidential information when they have access to it. If they do, they will stop knowing about things before the news are public and they will not be able to influence important processes like clinical trial protocol design early enough to make an impact.

IN SUMMARY, WHAT I RECOMMEND BASED ON MY EXPERIENCE

- Own the field. Be a field expert, not just a patient expert.You will do this by knowing everybody, putting together the room where conversations happen and having developed (or made available) the research tools.

- Be professional about it.Get advice from professionals, get advice from the industry, and if you are willing to invest funds in research then get professionals onboard that help you manage that.

- Collaborate with everyone – or at least talk to everyone - if they are professional about it. Don´t marry a lab, don’t avoid companies to remain free of conflict of interest. Ask to be treated with respect, for example by getting some feedback or update after you have met with a company to provide feedback on some of their work.

Let’s start an #ImpatientRevolution!

Ana Mingorance, PhD

Impatient series #3 – When is your disease field ready to attract the interest of companies

In the previous entry we discussed the many types of companies that get interested in rare diseases, each of them because of different reasons. If your disease field matches one of those business propositions you will get at the top of the list of interesting diseases for that company, but another part of the decision equation is time, or field maturity. Is this field ready for us to start working on it already The following are the questions that a company will often need to answer to be able to judge if the field is ready for them, too early for them, or maybe even too mature for them to get in.

In the previous entry we discussed the many types of companies that get interested in rare diseases, each of them because of different reasons. If your disease field matches one of those business propositions you will get at the top of the list of interesting diseases for that company, but another part of the decision equation is time, or field maturity. Is this field ready for us to start working on it already?

The following are the questions that a company will often need to answer to be able to judge if the field is ready for them, too early for them, or maybe even too mature for them to get in. Some of it applies to both large and rare diseases while some of the questions are more important for rare diseases.

If you work at a rare disease patient organization or research foundation, make sure you also ask yourself these questions:

o How many patients are out there? Some companies will be interested in diseases with as little as 500 patients, but others might have a cut off of 3,000-5,000 treatable patients. If the numbers are not known, or if they are too small, the probability of getting a company interested will be much much smaller.

o Is there already a drug approved that treats this disease in a satisfactory way? If a company can be the first-to-market it will be more interested in the disease.

o Who else is developing drugs for this same rare disease? The larger rare diseases might support competition, with multiple companies hoping to get a piece of the market, but if the disease is very rare one of the main drivers of companies to choose a rare disease, which is avoiding competition, will not make sense anymore.

o Do we know the cause of the disease and what is affected? This will help them see if your disease is a good match for their drug or technology, and even to see if they might have already have some already developed drug that could help your disease because it acts on the same signaling pathway.

o Are there good animal models of the diseases? Generally this is a mouse model. If there are good mouse models the company could either quickly test their drug to see if it has efficacy (if the drug already exists), or use it to confirm the efficacy of a future drug that they might want to develop. If there is no mouse model yet, some companies might worry that the disease might turn out to not be easy to model in a mouse, and that will make it harder to validate their drug in a relevant model prior to clinical trials. In some diseases, other animals are used to model the disease. What matters is if there is a good animal model that has symptoms in common with the patients or not, and if the company can have access to it.

o Are there other preclinical models available? The good mouse model is the bare minimum, for many research programs they will need to have access to DNA carrying the mutation and to cell cultures from patients.

o Is the patient population homogenous? Is there well-documented natural history? This is important to know which are the symptoms that need to be treated and to reduce patient variability. Patient variability is one of the problems of larger common diseases, and the reason of many trials failures. Therefore having patients that are very homogenous (diseases caused by one gene, for example) is a major attractive point of rare diseases.

o Could we find clinical centers willing to run clinical trials and patients willing to enrol? If there are too few specialists or they are not confident that they could find patients, companies will wait for the field to be ready.

o Would we know how to design a clinical trial? Depending on the disease symptoms it might be easy or not to know what could be measured during clinical trials to investigate drug efficacy. Not having a clear symptom to measure in a trial, what is generally called “an endpoint”, can be a major cause of clinical trial failure.

o Is there any previous case of regulatory agreement or approval? If the regulatory authorities (generally FDA or EMA) have already agreed with another company which endpoints are good, and how many patients are needed, and confirmed that they consider that rare disease a legitimate separate disease, then a lot of the regulatory risk has been lifted and more companies will be interested.

Because it takes time to be able to answer all of these questions in an affirmative way, some of the most recently described rare diseases will not be mature enough for companies to work on them. The next entry of the Impatient Series will address how, from a patient organization, you can advance research in your disease to the point and make it mature.

Let’s start an #ImpatientRevolution!

Ana Mingorance, PhD

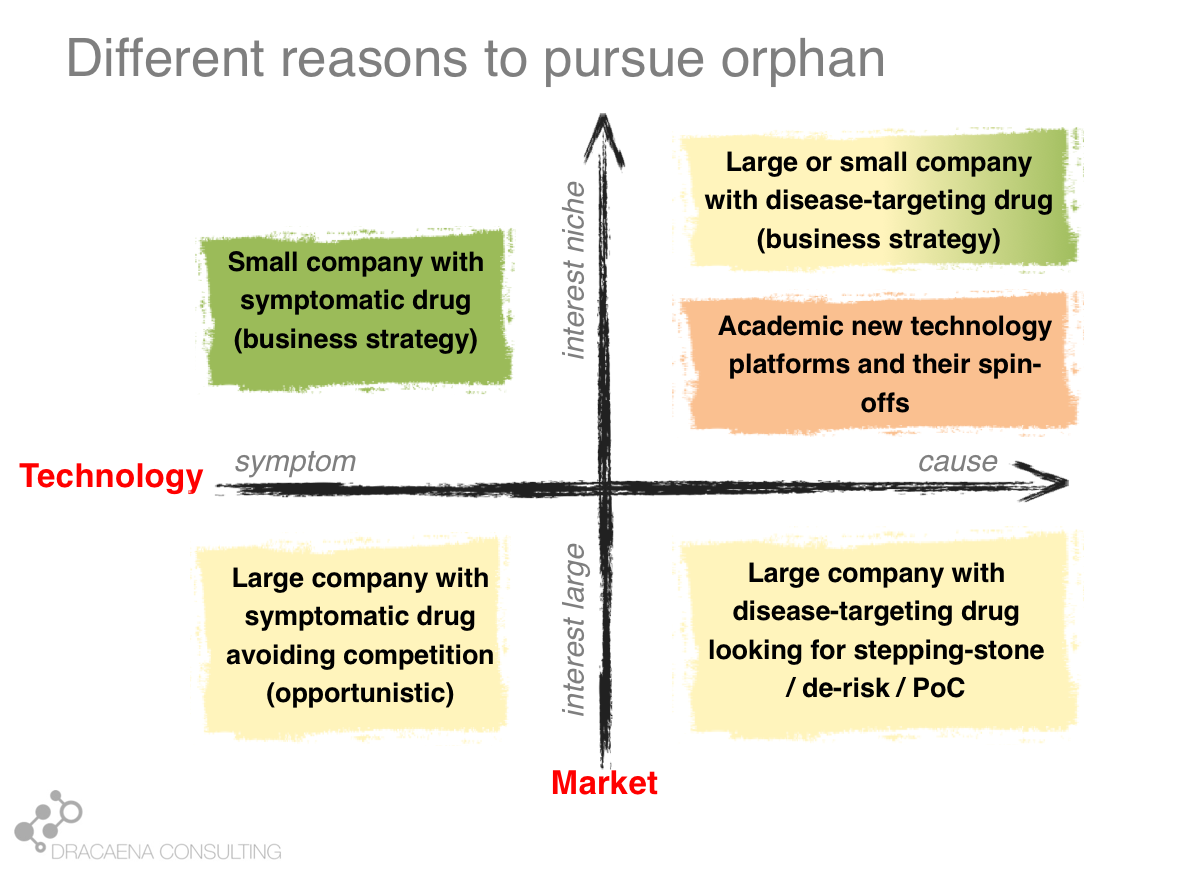

Impatient series #2 – What are companies looking for when choosing a rare disease

The number of orphan products in development keeps growing every year. A particular rare disease will be attractive for a drug development company if it matches one of four main business propositions determined by the interplay of market pressure and technology enablers. The degree of maturity of a field will also attract companies and help prioritize which disease to focus on where multiple rare diseases match the needs of the company or the drug that they are already developing

As part of these Series I will write about what patient organizations can do towards advancing research, even before a company gets interested in their disease. But before I can address that, we need to first define what gets companies interested in a disease in particular. That will then serve as the goal for patient groups: get your disease field to the point where it can attract companies.

As a side note, some diseases will be so rare that they won’t be able to attract companies. In those cases, if patient organizations need to carry out all of the research and development activities, they will still need a field that is mature enough to support drug development efforts.

I will address this in two parts: first, why companies get interested in rare diseases, and second, why do they choose one rare disease vs another.

PART 1 – CHOOSING ORPHAN

The number of orphan products in development keeps growing every year. Therapies are called orphan when they target a rare disease, which were traditionally orphan in the sense of not having any medicine to treat them. But nowadays some rare diseases have multiple “orphan” drugs to treat them, such as cystic fibrosis, and they are still called orphan drugs.

Companies have been driven towards rare diseases for a combination of reasons. The main ones are probably a market push (away from large markets) and a technology pull (towards rare diseases):

A market push: some of the larger markets got so crowded that it became very difficult for companies to get a competitive price. This has been called the “better than the Beatles” problem. Imagine if every new musician would need to show that they are better than the Beatles in order to get a record out – this is what new drugs must demonstrate in order to get approved and be successful in the market. The rare disease space, however, represents a broad landscape of virgin diseases, for which no drug (or Beatles' song) has ever been approved, and where an effective and safe drug will be commercially rewarded.

A technology pull: with the development of new technologies, particularly genomics, we have been able to understand that what we thought were common diseases are in fact a collection of separate (genetic) rare diseases. Other technologies such as gene therapy and antisense therapy have also enabled us to treat these diseases, in a way that we could have never imagined some years ago.

Drugs developed to treat rare diseases also enjoy of some regulatory and market incentives, which were developed by the regulatory agencies to attract drug developers to this space. The most valuable one is probably the 7 to 10 years (US vs EU) of market exclusivity after approval during which no competitor can have a similar drug approved for the same disease (a generic). But this aspect is less important for patient organizations. Instead we should try to understand how the market and the technology might drive a company to our rare disease.

Looking at the interaction between the market push and the technology pull we can differentiate 4 types of companies that get interested in rare diseases or 4 types of programs within a company that might be directed towards a rare disease:

1- Companies that want large markets and use old technologies: These are your classical large pharma companies, that have the pockets that are needed to pay for clinical development in large diseases, and that are developing a traditional drug, usually a small molecule that can improve an important symptom. These companies have transformed the way we treat common diseases like diabetes or cardiovascular diseases and still produce the same type of drug, but today the problem is the market push that scares them away for the large diseases because there is too much competition and the requirements for pricing and reimbursement are too high. This is how a company that had a drug perfectly good for a large market, and that prefers large markets, finds itself developing their molecule for a rare disease that has that common symptom in order to avoid the competition.

2- Companies that want small markets and use old technologies: Some companies develop the same type of molecule that could treat common diseases but have decided to focus on rare diseases as part of their business model. This is usually the case of smaller companies, which don’t have sufficient money to go after the common diseases. Smaller companies often focus on smaller diseases because those are the ones where they can afford to take a drug all the way through clinical trials and into the market. A second type is when the molecule is an old drug. In these cases the orphan drug market exclusivity that I described before becomes very important and makes the company focus on a rare disease so that they can have product protection (since they don’t have a patent on the drug because it is an old drug). These companies focus on rare diseases because it is cheaper to take orphan drugs to the market and because of the market exclusivity.

3- Companies that want large markets and use new technologies: Some of the large companies, which like to go after large diseases, are also adopting new technologies. This allows them to go straight to the cause of the disease, in what we could consider personalized medicine. In these cases where the therapy targets a disease cause, not just a symptom, rare diseases that share that cause become very attractive as part of the drug development pathway. Imagine for example a company that wants to develop a medicine for Alzheimer's disease by creating a molecule that targets the protein “tau”, which is very important in Alzheimer's. Such company knows that most trials in Alzheimer´s disease fail, and that they cost many hundreds of millions of dollars. So such company will most likely choose to first test their drug in some monogenic taupathy (i.e. a rare disease caused by a problem in tau) to make sure that the drug does what it should, before risking costly Alzheimer’s disease trials. The rare disease becomes a stepping stone in the development program. This is another scenario in which a company that is going after a large market finds itself developing their molecule for a rare disease in order to de-risk their program.

4- Companies that want small markets and use new technologies: And last we have the companies that are focused around a technology platform that usually means they can target genetic causes. These companies working on new technologies such as gene therapy and other personalized-medicine approaches work on rare diseases because these are largely caused by genetic problems, so they are the perfect match for companies (large and small) that are using the new technologies. These are the companies most likely to specifically develop from scratch a therapy ideally designed for that rare disease, and to target the cause. These are the companies (and the business scenario) most likely to lead to the type of treatments that we could call cures.

Some diseases become popular for only of these business reasons. Others fit multiple boxes. It is important for each rare disease patient organization to identify which of these boxes they fit, so that they know how to target their efforts and conversations.

PART 2 – CHOOSING ONE SPECIFIC DISEASE

Q1 - Does it fit our business needs?

Your rare disease will be attractive for a drug development company if it matches one of the four main business propositions (previous graph):

1 - My drug discovery expertise is in epilepsy. The field of epilepsy got very crowded, with over 30 drugs approved, so pretty much every company in the sector started looking at the orphan epilepsies to avoid the competition. Except for some cases, most of their drugs are molecules that could have easily treated epilepsy in general, since they just treat the symptom (seizures) and not one of the many epilepsy causes. But the companies chose to work on the orphan space to avoid competition. That is how rare syndromes with epilepsy “got lucky”. Prader-Willi might be an attractive target for a company that is concerned about competition in the obesity market. Neurodegeneration is another field where companies are moving towards rare diseases, in this case due to the high failure rate in the larger diseases. If your disease has a common symptom and the general market is saturated it might attract these companies.

2 - A company with an old molecule will most likely be looking for a rare disease due to the need of securing some years of market exclusivity in the absence of a drug patent. Often this happens when the company has discovered a new property that the old drug has, which creates the possibility of developing for that new use. In this case they will be looking for a rare disease that matches that new use, either due to its cause or due to its symptoms. Also, some small companies developing molecules that could treat broad diseases choose to focus on the orphan space because they can't afford the large and lengthy trials that broader diseases demand. One example could be the multiple small companies going after autism, which often decide to target genetic syndromes with autism even if their drug is not specific for the syndrome.

3 - The large company that is targeting a molecular cause of a large disease will most likely be interested in identifying a rare disease that results from that same cause. Some diseases become quite popular as monogenic examples of large diseases. I am a neuroscientist, so I often use taupathies as an example of stepping stone. Gaucher disease also shares biology with some forms of Parkinson, so companies targeting glucocerebrosidase for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease are likely to run their trials first in Gaucher’s disease and only risk moving forward with Parkinson if the drug has good results. There are examples of this strategy in all disease areas.

4 - Companies or research programs that are built around a platform technology often have a series of requirements that the target disease must meet in order to be a good match for the technology. A good example is a great young company called Stoke Therapeutics, which has discovered a way to increase protein levels by targeting a step between the gene sequence and the protein production (excuse my vague descriptions for the sake of non-expert understanding). Because of their particular technology, Stoke is interested in diseases that couldn’t be treated with gene therapy (maybe because the gene is too large for “traditional” gene therapy), that is also not amenable to protein replacement approaches (so the protein cannot be a soluble enzyme, for example), that needs more levels of a given protein (and not less levels) and that has one good copy of the gene for their therapy to act on. Each technology will impose a different set of requirements.

It is important to remember that the same disease might be a good match for one of these technologies AND be mechanistically linked with a broader disease so it can be a stepping stone AND have some common symptom that makes it attractive for the opportunistic companies. In other words, each company might be interested in your rare disease for a whole different reason!

Q2 - Is the field already mature?

The previous question asked whether a particular company should be interested in your disease. The question about field maturity essentially asks if they should be interested in your disease NOW. It will also help prioritize which disease to focus on where multiple rare diseases match the needs of the company or the drug that they are already developing.

We will discuss this in the next entry of the Impatient Series.

In the meantime, let’s start an #ImpatientRevolution!

Ana Mingorance, PhD

Impatient series #1 – What patient organizations mean when they say they are doing research

Most patient organizations, no matter how small, start with the same mission: to raise awareness and funds for research in their disease. But what research are they doing? are they all starting in the same place? and do they all evolve to run the same type of research? In my experience there are many types of strategy and approaches that patient groups take, in particular when they are starting. What a patient organization means when they say “we are doing research”, therefore, hides many different possibilities. The article describes some of these types, and discusses their advantages and disadvantages.

When we could only look at symptoms, there were less diseases. Now that we can also look inside a cell and see specifically what went wrong, we are uncovering new diseases, thousands of them. This means that for a lot of people, the disease that they have or that their child has is quite new to science. So in the true spirit of impatient patients, some of those patients come together and start a patient organization.

Most patient organizations, no matter how small, start with the same mission: to raise awareness and funds for research in their disease.

But what research are they doing? are they all starting in the same place? and do they all evolve to run the same type of research?

In my experience there are many types of strategy and approaches that patient groups take, in particular when they are starting. Although no two are the same, they do fall overall into some big types. To make things more complicated, what a patient organization funds in year 1 has often little to do with what they fund some years later. The field has evolved by then, the organization has evolved, the board members might be different… What a patient organization means when they say “we are doing research”, therefore, hides many different possibilities.

Here are some of the strategies that I’ve seen:

Type 1: We just need to exist

There is a tricky catch-22 situation where in order to raise funds (which you would hope to use for research) you have to already show you are a successful patient organization that funds research. Beyond friends and family, you will have to show most other donors where their money is going and how much of an impact it is making. Essentially: you need to be already funding research.

Because of this, your first few projects are critical to show the world that your patient organization exists and that it funds research. The quality of what you fund is in fact secondary. In many cases the project(s) take place at a university located near the headquarters of the patient organization. This might get you into some local press release, provide you with a scientist to refer to when you need some interviews, and essentially get your ticket punched. Congratulations, you now have a patient organization that does research, and from there you can start building a more solid longer-term strategy.

Type 2: Marry a lab

The first researcher that approaches a patient group, in particular if it is a newly-described rare disease, sometimes goes on to become their official lab. As in the previous case, this often happens with organizations that are just starting off. For the next couple of years, the organization will raise funds to finance research at that main lab, which then becomes a referent in the field for that disease. These patient groups appear to be married to that initial lab.

Getting funding for academic research as an academic lab head is very hard. And if it is a new research area for that lab, it might be impossible. So, for some academic labs, receiving funding from those patient groups is the only way to advance their science during the first couple of years until they have generated enough data and publications about the new disease to be able to receive public funding. In a way, the patient group didn’t marry the lab, instead they adopted the lab until it was mature enough to become financially independent.

This is a good strategy when the patient group doesn’t have enough funds to finance multiple projects or labs and when the field is just starting. In this case, the patient group might choose to focus its resources on building a first solid lab, which will pretty much start building the entire research field. This is how some patient groups are doing research.

This strategy, however, can backfire in many ways. One of such scenarios is when the patient group leadership comes to believe that they should not fund other labs because they owe to this initial lab some loyalty in return for their early support. It blurs the line between grantee and patient group and could lead to big conflicts among the patient group leaders. Another potential negative outcome is not having much to show for after supporting the same lab for several years. This happens when the lab learns to see the patient’s money as easy money and not dedicate enough efforts to the project to make an actual tangible progress, unlike they would do for regular external funding.

In short: it is a respectable strategy to adopt one lab and start building a field, but it must be done with a clear outcome in mind, which is agreeing with the lab that they should dedicate those early efforts towards generating compelling data to become financially independent from the patient group. It must to be bridge funding, and not funding for life.

Type 3: Let the advisors decide

When patient organizations have enough funding to support multiple programs, they often choose to surround themselves with a handful of experts that will become their scientific and medical advisors. In many cases, they ask these advisors to tell them where to invest their research funds.

Often this is done by having an annual call for grant applications and then having the advisors and some external experts that they nominate evaluate the grants and rank them. Then the patient group will fund the top ranked proposals. This is how some patient groups are doing research.

One thing I don’t like about this strategy is that it is often bottom-up, with the external scientific community proposing what they would like to do and the patient group then picking the most scientifically excellent ones. I believe research funding should be more strategic and therefore more top-down, but there are ways to achieve a healthy balance.

My main concern with the advisors deciding where to invest is that in some cases a patient group ends up funding every year the same 4 or 5 labs, which happen to be the labs of their scientific and medical advisors and/or their close collaborators. If one can guess who your advisors are by seeing who you fund, you are an organization that has essentially followed the Type 2 strategy of marrying a lab. You simply have married you advisory board.

The debate inside these organizations after the first couple of years is usually the same:

Board member 1: Why are we always funding these same labs? This endogamy of having the advisors finance their own labs is disturbing.

Board member 2: Well, we chose as advisors the leaders in the field, so it is only natural that we also finance the best research… which happens to be the one coming from their labs.

Board member 1: I am not comfortable with the conflict of interest of having the advisors decide where the funding should go after seeing that so much ends up in their own labs or their friends’.

Board member 2: What should we do then? Remove the leaders of the field from our advisory board? Or stop funding the best research out there?

And then board member 1 leaves the organization.

My recommendation, if you allow your advisors to also receive funding, is to ask them to guide you through what should be the main research priorities but then use external reviewers to score the grant applications that fit those priorities. Ask the advisors to pick the priorities, not the awards. I would also consider having a condition to be part of the advisory board, which is that your lab cannot receive funding from that organization. For good established labs that are indeed the best in the field this should not be a problem (see comment on previous sections about bridge funding).

As a side warning: if you are a scientist considering applying to one of the call for grants of a patient group, make sure you review where their funding is usually going. You might think it is an open call for grants, while in reality it is a closed group of advisors and their closest collaborators getting as much funding as they can out of a patient organization. We all know examples of this.

Type 4: Owning the roadmap - the top-down approach

Anyone who has read the #ImpatientRevolution eBook knows that this is my preferred approach. Patient organizations cannot aspire to outfund NIH or their applicable national research funding body outside the US. What patient organizations can do with their research funds is to complement it, by identifying those areas that are essential for developing new medicines for their disease and that are currently not being pursued (or not fast enough). Then they would focus on those areas, ideally on setting up the basis so that good scientists can be attracted to those areas and bring more (non-patient) funding. This is how some patient groups are doing research.

I won´t extend on this strategy because the eBook covers much of it. But before wrapping up, here are some aspects of research funding strategy that I would like you to consider:

a) Bottom-up vs top-down

Do you want to collect external ideas and fund the best ones or do you want to analyze the field, identify the gaps and address those first?

Depending on your finances I recommend following a top-down strategy only, or a combination of both. For example:

Fund some projects that the organization has identified as a priority for the field. In those areas you identify what is needed and then go out and find the best lab or contract research organization to do that. This is probably the boring science, the type that no academic lab would propose in a call for grants because it is not conductive to exciting publications and promotions. It is, however, needed to develop cures.

At the same time, have your advisors identify where your priorities should be (for example biomarkers and a gene therapy with large capacity virus), and then have a call for grants on those topics. The call for grants would then be evaluated by a broader team, not just the advisors.

b) Projects vs enabling

I believe the greatest return on investment comes from generating the tools that will enable the scientists to then work in your disease and bring in their own external funding. For example, make sure that there is a good antibody, a good mouse model, iPSCs from patients, and that all of this open access. Make sure you have identified and helped set up clinical centers of excellence, and maybe some biomarker or outcome measure. Make sure there is a registry, or at the very list a way to reach out to families (a contact database). This toolbox serves both as a starter package and as a strategy to de-risk the field. With these things in place you will attract researchers and companies to your disease, and they will bring their own funding. They will also be many more than those that you could have directly funded yourself, so you would have mobilized much more funding to your disease than what you could have raised in decades.

Many of those efforts are the boring science, so you will only identify them if you do some top-down thinking and analysis. You should decide what percentage of your efforts and resources should be allocated to the boring science (enabling tools, de-risking the field), and what percentage will go to giving an opportunity to new exciting projects to develop.

c) Organization aging and cycles

Young organizations and old organizations think differently. The first two strategies I covered, for example, are much more common in younger organizations. I would recommend you to revise your strategy every 3 years and see what is working for you and what is not working. Older organizations also tend to grow more complex, and are more likely to engage professional staff.

I tend to work with patient organizations where the members of the organizations are parents of children with severe rare diseases. This has also helped me see another pattern, with parents of younger children being more optimistic and driven and investing in more high-risk projects, while parents of older children being more likely to make safer investments or to even move away from research and into care support programs. A parent of a 3-year old might want to invest in gene therapy, while the parent of a 13-year old might be more concerned with developing devices to assist with mobility issues, for example.

And add to this complexity the burnout factor. I´ve seen organizations that are centered around one person that can last many years, but those that rely on a group of core members can experience changes over time. I estimate a 3-5 year burnout time, before new members need to take over and continue the life or the organization.

Because of this, the same organization in year one is very different to the same organization in year seven. The members are different, the strategy is different, and what they mean when they say “we do research” is also different.

Let’s start an #ImpatientRevolution!

Ana Mingorance, PhD

Impatient series #0 – The impatient series