Epilepsy Insights

Looking ahead: Dravet syndrome news during 2018

we expect in 2018 the first approval of a treatment for Dravet syndrome in the US, the results of clinical trials with three new therapeutics (ZX008, ataluren and OV935/TAK935), and the initiation of the first clinical trial ever done with a disease-modifying therapy designed to treat Dravet syndrome (OPK88001). 2018 is going to be a good year.

I was talking yesterday with some friends that have children with Dravet syndrome, and they asked me about what news we can expect in 2018 from those programs that are in clinical trials for Dravet syndrome.

For them, and for anyone interested, here is what we can expect in 2018 from the clinical programs from GW Pharmaceuticals, Zogenix, Ovid Therapeutics and Takeda, PTC Pharma and NYU, and OPKO Health, based on what these companies have communicated.

First quarter 2018

No big news expected this quarter around Dravet syndrome unless OPKO Health announces the initiation of the clinical trials with their antisense oligonucleotide OPK88001 [4]. This product was expected to start pilot trials in the second half of 2017 or first half of 2018. OPK88001 is the first disease-modifying treatment to be developed for Dravet syndrome and a potential game-changer.

Second quarter 2018

This is a very exciting quarter for Dravet syndrome. FDA has June 27 as the deadline to make a decision on the approval for GW Pharma Epidiolex to treat Dravet and Lennox-Gastaut syndromes [1]. Around the same time, Zogenix will announce the results of the second large Phase 3 clinical trial in Dravet syndrome with fenfluramine [2]. If the data are as strong as the first clinical trial the Dravet community will have fantastic news for their International Dravet Syndrome Awareness day (June 23rd).

Around the same time we expect also the results of the pilot study of ataluren in Dravet syndrome and CDKL5 deficiency disorder that is taking place at NYU [3]. This is an investigator-initiated trial, not a pivotal trial, but the placebo-controlled double-blind design makes it a very important trial to evaluate the potential efficacy of ataluren in children with nonsense mutations in SCN1A (Dravet syndrome) and CDKL5.

Third and fourth quarter 2018

The third quarter arrives with the required DEA rescheduling of cannabidiol (90 days after the FDA approval), followed by a potential launch in the last quarter. The epilepsy community meets every year during the first week for December for the American Epilepsy Society meeting and if there are no bad surprises Epidiolex should be the star of the 2018 meeting with an imminent launch.

Around the same time, Zogenix will file an NDA for the treatment of Dravet syndrome with ZX008, which a potential launch one year behind Epidiolex. Zogenix also has an advanced clinical trial program for Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome, with a Phase 3 trial ongoing based on a positive Phase 2 dose-finding study.

We also expect to hear before the end of 2018 about the results of the second large Phase 3 clinical trial of Epidiolex in Dravet syndrome and the Phase1b/2a clinical trial of OV935/TAK935 in a basket trial including patients with Dravet syndrome [4].

In summary: we expect in 2018 the first approval of a treatment for Dravet syndrome in the US, the results of clinical trials with three new therapeutics (ZX008, ataluren and OV935/TAK935), and the initiation of the first clinical trial ever done with a disease-modifying therapy designed to treat Dravet syndrome (OPK88001).

2018 is going to be a good year.

Ana Mingorance PhD

Sources:

[1] GW Investor Presentation, January 2018

[2] Zogenix Investor Presentation, January 2018

[3] Dr Devinsky at CDKL5 Forum, December 2017

[4] OPKO health press release August 8 2017

[5] Ovid Therapeutics Corporate Presentation, January 2018

Announcements within the same quarter ordered by drug name (alphabetic).

Top 5 insights from the American Epilepsy Society meeting

Every year the American Epilepsy Society (AES) meeting gets larger. This year AES meeting was very positive, showing a great progression of the field that now moves towards orphan indications (with new drugs and clinical designs), where patient organizations gain relevance (also a characteristic of the orphan drug field), and where we start having new drugs able to break the barrier of pharmacoresistance.

Every year the American Epilepsy Society (AES) meeting gets larger. This year, over 5,500 people got together in DC to discuss the latest information about epilepsy care and the development of new treatments for epilepsy.

I’m a scientist looking for a cure for a rare disease called Dravet syndrome. I first attended this conference as a pharma scientist working on new epilepsy therapeutics, later as the head of research of a Dravet syndrome patient organization, and currently as an independent consultant specialized on rare epilepsy syndromes. Because of my background, I look at this conference from the perspective of a drug hunter, a patient advocate and an industry analyst, and I must say that from all of these perspectives the 2017 edition of the AES meeting was an exceptionally interesting one.

Here is the list of what I found the most interesting at the AES meeting:

1- There is a change in epilepsy drug development towards orphan drugs.

I wrote earlier this year about Everolimus and how orphan drugs are reviving the field of epilepsy. This was very visible at the AES meeting as well. Two of the likely next approvals in epilepsy, based on their positive Phase 3 trial results, are targeting rare forms of epilepsy. These two drugs, cannabidiol (Epidiolex, GW Pharma/Greenwich Biosciences) and fenfluramine (ZX008, Zogenix), were the focus of much excitement and interest during the conference. At the same time, I couldn’t help but miss some of the largest companies that used to have much floor space at the exhibition hall in former AES meetings, like Pfizer and GSK. The pharmaceutical giants are leaving, and smaller companies with orphan drugs are filling in their space. Some loyals like UCB, Eisai and Sunovion are still staying, but times are certainly changing in epilepsy drug development.

2- Pharmacoresistant epilepsy is not forever.

We are all used to hearing that despite having many anti-epileptic medications in the market, about 30% of people with epilepsy continue to have uncontrolled seizures. This includes the large majority of the genetic epilepsy syndromes, although it goes well beyond these rare diseases. Breaking into that 30% is the Holy Grail of epilepsy drug development, and the small company Zogenix managed to pull an Indiana Jones move this year with their drug ZX008. In their recent Phase 3 clinical trial in Dravet syndrome, 25% of the patients randomized to the highest dose of fenfluramine (ZX008) had zero or 1 seizure during the 3 months of treatment. That would be 4 or less convulsive seizures in a year, down from a baseline of approximately 40 convulsive seizures per month, or about 500 per year. The median percent of seizure reduction at that dose was an impressive 72.4% versus 17.4% with placebo. The sessions organized by Zogenix during the AES meeting were among the best attended ones, and their results have given us hope in the orphan epilepsy community to dream with seizure freedom, a goal previously though to be unrealistic. Pharmacoresistant epilepsy, now we know, is not forever.

3- There are too many genetic epilepsy syndromes to not use gene panels as soon as possible.

Diagnosing correctly a child that has refractory epilepsy or epilepsy combined with neurodevelopmental problems is not easy, because there are many syndromes that look very similar or overlap substantially when it comes to clinical criteria. It is just too complicated to try to diagnose any of these diseases based uniquely in their clinical characteristics, so epilepsy specialists should consider epilepsy gene panels as a necessary and urgent test for all cases of childhood epilepsy as soon as they first see these patients. Walking around the patient advocacy area at the AES exhibition hall and trying to understand the characteristics of each syndrome was overwhelming: Dravet, Lennox-Gastaut, Tuberous Sclerosis Complex, SCN2A, PCDH19, CDKL5, STXBP1, SYNGAP1, GLUT1, KCNQ2, Batten disease. These are just the tip of the iceberg, represented at the conference by brave parents that know it is important to get their disease name in front of the specialists. And together they send a strong message to epilepsy specialists: there are just too many syndromes to not use gene panels as soon as possible.

4- The arrival of basket trials to epilepsy.

Just as it is important to be aware that epilepsy includes many individual rare syndromes, it is also important to figure out how we are going to develop therapies for all of these syndromes. A year ago at the AES meeting no one had publicly heard about the experimental drug TAK-935. It was already 2017 when Takeda and Ovid Therapeutics announced that they were partnering around this program, and that they intended to develop it for a variety of epilepsy indications. This year at AES there were multiple presentations on TAK-935 and for me the most interesting aspect is the clinical trial design: a Phase 2 basket trial combining patients with three different orphan epilepsy syndromes. In the epilepsy field we had already seen this type of basket trial in investigator-initiated studies, such as the first open-label studies with Epidiolex in the US that served as the basis for the single-syndrome placebo-controlled trials that followed, but not in a company-sponsored placebo-controlled trial. I find the basket trial approach a fantastic innovation for the epilepsy field, and I already developed these thoughts it in more detail in a previous article about genes versus syndromes.

5- Beginning to understand the dark side of epilepsy: SUDEP.

Sudden death in epilepsy (SUDEP) is a scary topic. Doctors don’t want to talk about it, in particular because we don’t understand it enough to be able to do something about it, and patients and families would also prefer to not have to hear about. Dravet syndrome has a particularly high incidence of SUDEP, so it is a field that I follow closely. Fortunately there is much research and growing awareness on SUDEP, and we could see at the AES meeting very valuable research that gets us closer to understanding how SUDEP happens. Some time ago it was thought to be of cardiac origin, but nowadays we know that SUDEP starts in the brainstem, and that it is essentially a seizure during sleep that originates or spreads to the brainstem area causing a shutdown of the neurons that control breathing, followed by respiratory arrest and cardiac arrest.

This year at AES we saw research using a mouse model of Dravet syndrome that showed that the brainstem circuits that regulate breathing are dysfunctional in this syndrome, and could trigger hypoventilation when the response should be hyperventilation to increase oxygen saturation. We also saw clinical research in patients with Dravet syndrome that showed that there is also an increased parasympathetic tone during sleep leading to very low heart rate. The extraordinary practical value of these findings is that patients could wear sensors that would produce an alert when oxygen saturation and heart rate drop below regular seizure thresholds and alert a caregiver trained in CPR techniques, which are known to be at times efficacious when practiced early in cases of SUDEP.

Overall, I felt that this year AES meeting was very positive, showing a great progression of the field that now moves towards orphan indications (with new drugs and clinical trial designs), where patient organizations gain relevance (also a characteristic of the orphan drug field), and where we start having new drugs able to break the barrier of pharmacoresistance and the understanding needed to detect, and hopefully prevent, the big problem that is SUDEP.

For those of you that also attended the AES meeting, I would love hearing about those trends or progresses that you felt were the most interesting ones!

Ana Mingorance, PhD

Genes vs syndromes at the International Epilepsy Congress in Barcelona

Should we talk about syndromes based on the gene that causes them or should we talk about them (and treat them) based on the clinical characteristics that they display? Earlier this month, the epilepsy community gathered in Barcelona for the 32nd International Epilepsy Congress and there was a debate between genetic and symptom-base syndrome classification. This debate goes beyond semantics, and has important regulatory and access implications.

THE DEBATE

Earlier this month, the epilepsy community gathered in Barcelona for the 32nd International Epilepsy Congress. There were three interconnected topics that dominated much of the program: genetics of epilepsy, rare epilepsy syndromes and personalized medicine. The other large topic that dominated the agenda was the new epilepsy and seizure classification by the ILAE, and it felt like two separate conferences.

While most scientists are looking inside the cell, looking for genetic changes, many practicing physicians are looking at what they can see, and creating new nomenclatures to define seizure types. And from the patient side this makes a large difference, because the same child with an SCN2A mutation might be diagnosed by a specialist as having SCN2A encephalopathy, and as having Dravet syndrome by another physician based on clinical symptoms.

There has been a trend in the recent years towards creating new syndromes that group patients by the gene that they have affected when their epilepsy is found to have a genetic cause. Some examples of this are CDKL5 deficiency disorder or STXBP1 encephalopathy, which until recently would have be classified as atypical Rett syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut or Ohtahara syndrome respectively, at least in most cases. And that is the catch, that the same gene mutation can lead to different phenotypes in different patients and actually manifest itself as a complete different syndrome.

We see this mismatch between gene and syndrome every day. For example, the nigh before I few to the congress a mother had contacted asking how it was possible that her daughter with Dravet syndrome had exactly the same gene mutation that another patient diagnosed with Ohtahara syndrome had. Then at the congress, Professor Jackie French from NYU presented the case of a family with an inherited mutation in SCN1A that included individuals with mild forms of epilepsies, for example just febrile seizures, but also one child with the much more severe Dravet syndrome. As a physician, she would adjust their medication to their seizure type and treat more aggressively the individual with Dravet syndrome, because their diseases are indeed different ones.

So what is the best classification approach? Should we talk about syndromes based on the gene that causes them or should we talk about them (and treat them) based on the clinical characteristics that they display?

This debate is not just about semantics, it affects a lot how well we develop new medicines and how many patients will benefit from them. So it is important that we get it right.

What follows is my personal view of which syndrome classification is best, when to use it, and what regulatory changes are needed in order to get more medicines to all patients with rare genetic epilepsy syndromes.

OVERLAP BETWEEN SYNDROMES AND GENES

The way I see the debate between genetic and symptom-base syndrome classification is that they are not exclusive; in fact, they form a matrix where many of the epilepsy genes can produce phenotypes that fit into many of the classical (phenotypic) syndrome boxes.

For illustration purposes, I’ve selected a handful of genes and syndromes and created the matrix below. While not all of these genes are found in all of these syndromes, what we have to remember is that many of the epilepsy genes are present across a large number of epilepsy syndromes.

With this in mind, what would be the correct diagnosis for the child of the previous story that had a diagnosis of Ohtahara syndrome before performing genetic testing but was later found to have an SCN1A mutation (typical of Dravet syndrome)? Should the genetic finding change the diagnosis to Dravet syndrome?

I would argue that both a genetic and a clinical diagnosis are needed, so the best diagnosis for this child, if his clinical symptoms are indeed a better match for Ohtahara than for Dravet syndrome, would be “Ohtahara syndrome caused by SCN1A deficiency”. And the other child in the same story would have “Dravet syndrome caused by SCN1A deficiency”. Except for a few truly monogenic syndromes, most epilepsy syndromes have many possible genetic (and sometimes non-genetic) etiologies, and most epilepsy genes produce multiple phenotypes, so I don’t need we need to prioritize the symptomatic classification over the genetic one or vice versa; both are useful and both are necessary. Instead, we should point to the right box in the matrix when diagnosing a patient, which provides both sets of genetic and clinical data.

My purpose when creating this visual matrix is not to break down already rare syndromes into even smaller diseases. On the contrary, the purpose of this exercise is to make the syndrome classification more flexible, so that we can cluster syndromes, and create more flexible indications for developing new drugs and for treating more patients.

REGULATORY IMPLICATIONS

For as long as we didn’t have a good understanding of the genetics behind epilepsy, we have been perfectly OK with symptomatic epilepsy classifications. But the progresses in genetics in the recent decade, and the appearance of many new “genetic epilepsy syndromes”, has opened the door to the development of new drugs that specifically target those genetic defects, creating a new regulatory landscape where our former classification of syndromes based on symptomatology falls short.

The patient groups are already confortable using the genetic syndrome classification, the conference rooms talk more and more about personalized medicine and genetic syndrome classification, and companies pipelines start getting populated with programs that specifically target those abnormal genes and proteins that cause these epilepsies. The next step is to start using the genetic syndrome classification as a suitable drug indication in the drug development process as well.

Let’s go back again to the genes versus (phenotypic) syndromes matrix and see the different therapeutic implications of using one classification versus another.

The first example (scenario A) corresponds to the current preferred way of selecting drug indications. There are 8 different products that have received the Orphan Drug Designation to treat Dravet syndrome. This makes sense because Dravet syndrome has been recognized as a separate clinical syndrome since 1978, way before the genetic mutations that give rise to this phenotype were uncovered. It also makes sense because all of the drugs approved or in clinical trial for Dravet syndrome are symptomatic, meaning that they are not treating any genetic problem.

In short: if the drug treats a particular cluster of symptoms that corresponds to a syndrome, then the best indication for that drug is indeed the classical (phenotypic) syndrome.

But things change when a drug in development specifically targets a disease gene, and this is what is happening right now with a program by OPKO Health designed to increase SCN1A gene expression levels. This product has received the Orphan Drug Designation by the FDA to treat “Dravet syndrome”, because about 80% of patients with Dravet syndrome have mutations or deletions in SCN1A, but would have been more appropriate to match the gene-targeting therapeutic with a genetic patient classification, and target “SCN1A deficiency” as the product indication, like in the scenario B.

If we stick to the classical (phenotypic) syndrome classification for the programs in development that target the gene or protein that are defective in patients, we will be unnecessarily limiting the number of patients that will benefit from that drug. It is clear that in the case of the OPKO program, the indication cannot be simply “Dravet syndrome”, but a subset of patients with Dravet syndrome caused by SCN1A deficiency. But how about the people that having the same SCN1A deficiency have received a different clinical diagnosis based on their symptoms? With the current indication, those people will not have access to such treatment because it will be off-label.

The specific program that OPKO is developing is oligonucleotide-based and therefore very invasive, requiring intrathecal administration, so it is not likely to be used in people with SCN1A mutations and milder phenotypes. But there are small molecule approaches also in development for SCN1A deficiency, and these should not have an indication restricted to a subset of patients with Dravet syndrome. The same will happen with drugs that modulate SCN2A, a related channel that produces multiple phenotypes when mutated and leads to multiple diagnosis. Asking the drug developer to seek approval for only a subset of patients in a rare disease would artificially restrict the number of patients that would benefit from that drug.

This is why we need to get confortable with drugs being developed for a genetic indication that overlaps but doesn’t match the classical (phenotypic) syndrome classification. At the other side of the approval line, physicians must also get confortable with patients having both a genetic and a symptomatic diagnosis so that they can receive both types of medications.

I do believe that indications based on a gene defect (gain-of-function or loss-of-function), when the drug treats the gene or protein that is altered in those patients, will be acceptable and soon become common. What I am more worried about is the need of a scenario C (see next) and the mismatch between the clinical practice and the regulatory pathway.

ADDING COMPLEXITY – SCENARIO C AND MULTI-SYNDROME INDICATIONS

There are drugs that don’t treat the disease (gene or protein) but the symptoms, in the case of epilepsy they treat the seizures, yet they get approved for treating a particular syndrome only. Staying on the example of Dravet syndrome, this would be the case of stiripentol (Diacomit), which is only approved for treating Dravet syndrome but it is simply a GABA-ergic modulator that has no biological reason to work only – or even preferentially – in this syndrome. It is basically a strategic corporate decision to focus on a given orphan indication. Another example is ganaxolone, also a GABA-ergic modulator, that has received Orphan Drug Designations for PCDH19 epilepsy and CDKL5 disorder and is in development for these indications, while there is no obvious biological reason to target those syndromes and no others.

I understand the appeal of orphan indications with limited competition, and how the incentives that the orphan designation brings make these drugs possible so that patients ultimately benefit from them. It is possible that without these incentives these drug developers would have never had the resources to bring forward their drugs to a broader (non-orphan) market. But things start changing when the same developer goes after many orphan epilepsies with a broad symptomatic drug, and we are seeing this right now with Epidiolex (cannabidiol, by GW Pharmaceuticals).

Let me first set one thing straight, I don’t think that GW Pharma is abusing the orphan regulatory route with Epidiolex, they simply have no choice. If they want to develop their product for a large number of patients with orphan refractory epilepsy syndromes, which happen to be separate indications under the traditional classification, they must develop a separate clinical development program for each syndrome. And because they have a broad-spectrum drug with the potential to treat many types of refractory epilepsy syndromes they are running clinical trials for Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, Dravet syndrome, Tuberous Sclerosis Complex and West syndrome. That’s four separate indications.

I wonder how many syndromes should a drug be approved for before it becomes clear that it should have a broader indication and label. In this case, the most appropriate indication would have been “epileptic encephalopathies” or “developmental encephalopathies” or similar, given that the drug appears to behave similarly in all of them. This is what the scenario C is about, drugs that treat a general symptom and should therefore have an indication that is broader than a single individual syndrome (or four).

Recently Takeda started a Phase 2 trial in collaboration with Ovid Therapeutics that is recruiting patients diagnosed with any type of epileptic encephalopathy for treatment with their drug TAK-935. This is what is known as a “basket trial”, where multiple indications are combined. Basket trials started in oncology but this is the first time that we see it run with a mix of epilepsy syndromes. The Takeda trial is not a pivotal trial so it won’t lead to an approval, but it gives me hope that we will one day see this mix of refractory epilepsy syndromes considered as a single indications for drugs that, like the Takeda drug, have mechanisms of action that don’t make them specific for one particular syndrome. As I see it, the basket trial approach should be the future trial design for such drugs, and the broad-label indication should also be the preferred indication unless the product has reasons to only work in a particular syndrome or seizure type.

An interesting consequence of broadening the indication towards this “umbrella” indication might be that it is not longer considered orphan, and therefore the product is no longer eligible for the orphan development pathway and incentives. The answer to this question has important regulatory and commercial implications.

Last, one of the most important aspects of this broad-label scenario C is not the benefit it might bring to drug developers, but the impact it will have towards making sure that all patients with rare epilepsies get access to new medications. Some of the syndromes have patients that can be counted in the low hundreds or even less. The best way to facilitate the development of new medicines for these ultra-rare syndromes is making it possible for them to go together with the other syndromes that share common phenotypes when it comes to evaluating and approving symptomatic drugs. This approach makes medical sense because it is also the same way that physicians work with these syndromes in their regular practice, and it will enable them to stop relying on off-label use of medications.

THE FUTURE

In conclusion, we have a few things to work on when it comes to the debate between genetic and symptom-base syndrome classification:

– First, we need to understand that both classifications are needed because they address different aspects of the disease: the cause and the clinical manifestation.

– Second, as drugs that treat the genes/proteins and not just the symptoms get into clinical trials, we need to be willing to switch from indications that follow the classical (phenotypic) syndrome classification to indications that reflect the drug mechanism so that it can be used across multiple classical syndromes.

– And last, we need to identify better regulatory pathways to make sure that the ultra-rare syndromes can get drugs approved for them as well. In the case of epilepsy this means considering the umbrella indication of epileptic encephalopathies or similar as opposed to artificially slicing indications unless the drug has a syndrome or seizure type-specific mechanism of action.

I hope all of these points will also create a new debate and have an important position in the agenda of the next the International Epilepsy Congress. Until then, I would appreciate your comments and thoughts.

Ana Mingorance PhD

Dravet Syndrome Drug Development Pipeline Review 2017

June 23 is a special day for families of people with Dravet syndrome. It is the International Dravet Syndrome Awareness Day, that in 2017 celebrates its 4th edition. That's why today we announce the publication of the 2017 Dravet Syndrome Pipeline and Opportunities Review, a market research publication that provides an overview of the global therapeutic landscape of Dravet syndrome.

June 23 is a special day for families of people with Dravet syndrome. It is the International Dravet Syndrome Awareness Day, that in 2017 celebrates its 4th edition.

That's why today we announce the publication of the 2017 Dravet Syndrome Pipeline and Opportunities Review, a market research publication that provides an overview of the global therapeutic landscape of Dravet syndrome.

Dravet syndrome is an orphan epilepsy disorder with multiple non-seizure comorbidities and high unmet medical need. The disease has recently gained significant attention as an orphan indication within epilepsy, and as of June 2017, the drug drug development pipeline for Dravet syndrome comprises at least 13 drug candidates, of which 3 are in late-stage, placebo-controlled Phase II or III studies. Two of the products in development are potentially disease-modifying treatments, and 8 different products have received orphan drug designations.

The report includes the most recent updates on Epidiolex (cannabidiol) from GW Pharmaceuticals; ZX008 (fenfluramine) from Zogenix; Translarna (ataluren) from PTC Therapeutics; BIS-001 (huperzine) from Biscayne Neurotherapeutics; OPK88001 (CUR-1916) from OPKO Health; OV935 (TAK-935) from Ovid Therapeutics and Takeda; EPX-100, EPX-200 and EPX-300 from Epygenix Therapeutics; cannabidiol from INSYS Therapeutics; a Nav1.6 inhibitor program from Xenon Pharmaceuticals; and SAGE-324 from Sage Therapeutics.

The 2017 Dravet Syndrome Pipeline and Opportunities Review also includes an analysis of the competitive landscape and evaluates current and future opportunities of the Dravet syndrome market.

The report is now available in this site.

Ana Mingorance PhD

7 Lessons from the World Orphan Drug Congress

Gene therapy is here, VCs want to invest in orphan drugs, Rettsyndrome.org foundation is doing a great work, the line between patients and drug developers is blurring, we should start talking about industry (not patient) engagement, networking is not always easy, and Fulcrum Therapeutics should be in your list of companies to watch.

Gene therapy is here, VCs want to invest in orphan drugs, Rettsyndrome.org foundation is doing a great work, the line between patients and drug developers is blurring, we should start talking about industry (not patient) engagement, networking is not always easy, and Fulcrum Therapeutics should be in your list of companies to watch.

That’s my 17 seconds version of the main lessons I got from attending the World Orphan Drug Congress in DC April 20-21. The WODC one of the largest meetings dedicated to the development of new medicines for rare diseases and takes place once in the US and once in Europe every year.

In a bit more than 17 seconds, here is the expanded list of what I would like to share with you from the conference:

1- Gene therapy is not a thing of the future, it is already here. I particularly enjoyed the presentations from Bluebird Bio and Spark Therapeutics. Nick Leschly from Bluebird Bio gave us excellent advice for building a rare disease company. My favorite: (1) if you have seen one company do it, you have seen one company do it (=every case is unique); (2) the power of n=1; (3) if you see great improvement for one patient you have to fight for that drug; (4) getting pricing reimbursement and adoption are the real end goal, regulatory approval is just the start; and (5) keep constructive paranoia, don’t get in the comfort zone, do something that has a lasting effect in a human being. Bonus lesson: videos of patients before and after gene therapy are always amazing. No graph with 200 patients has the power of showing a video of a child that was previously blind navigate a circuit with obstacles one year later.

2- Developing drugs is an expensive business and investors need to be part of the game…and the conferences. Listening to Venture Capital partners at the Pitch and Partner track was extremely interesting. A panel shared their views on what they look for in the orphan space, the concept of orphan vs ultra-orphan, how they work with academic founders and partner with patients, and best advice when pitching to them. It is a great decision to give a voice to VCs in orphan drug conferences. Also, Philip Ross from JP Morgan should be the moderator for all conference panels, or at least be in charge of the questions.

3- Anavex’s CEO Christopher Missling talked about partnering with patient organizations and explained that a year ago they didn’t even know what Rett syndrome was. He credits Rettsyndrome.org CSO Steven Kaminsky for making it very easy for them to test their most advanced drug in a Rett mouse model and for mobilizing resources to help them start a clinical trial when those results where very positive. They plan to start a Phase 2 trial this year. Rettsyndrome.org is a great example of how patient organizations can attract companies to their disease by proactively engaging the industry and understanding how to remove drug development bottlenecks, such as offering access to good animal models.

4- Times are changing. I met several parents of children with rare diseases that attended the WODC that have created their own companies or that are considering starting one. The line between patients and drug developers is blurring. There are more and more patients and parents that have turned drug developers, from the more senior John Crowley from Amicus to companies that are just starting. This trend is likely to make the biggest impact for ultra rare diseases.

5- I’m thinking we should start the hashtag #IndustryEngagement. I spent the last 5 years working with patient organizations trying to get the industry interested in our diseases. Our research strategy was to make it so easy for anyone to work on Dravet syndrome that we would have 300 labs and companies working on it tomorrow. That’s why Dr Kaminsky from Rettsyndrome.org is one of my heroes. And when I sit down with other patient organizations, as I did during the WODC, our conversation is always about best practices to engage the industry. We hear so much about patient engagement from industry speakers that I am not sure they know that the reverse conversation is also taking place under the same roof. I pretty much wrote an entire book about it. I’m thinking we might need to come up with a proper name for that reverse patient engagement. Let me know if you have other ideas about how to call it.

6- The WODC is multiple conferences in one. The conference places a big emphasis in networking, but there are so many vendors in attendance (CROs and similar) that the speed networking sessions and most networking opportunities where not useful for somebody like me. I’m not useful for them either, since I don’t use their services. All of my useful contacts but one happen by going through the attendees list and pre-programing meetings ahead of the conference. So here is my recommendation: maybe we could use different color badges for the different sectors. That way I will go straight to drug developers and patient groups and not struggle to find them in a sea of service providers.

7- Somehow I hadn’t noticed Fulcrum Therapeutics before. Or at least I hadn’t noticed how cool what they are doing is. Co-founder Walter Kowtoniuk gave an amazing presentation at the WODC that not only got me to fall in love with their approach but also with his passion. Fulcrum is doing small molecule regulation of protein levels through gene regulation. So many diseases are caused by having one defective gene copy and therefore another one to upregulate (or a copy to reduce, in case of gain of function or toxic function) that the sky is the limit. And they clearly know it, seeing their aggressive expansion and approach. I need to get them to talk with me about rare epilepsy syndromes!

And these are my main lessons from the WODC. I hope you also found them interesting.

This is the first time I attended the USA congress after having attended some of the European ones, and Terrapin always does a great work at putting together such a large and varied congress (see lesson #7). I look forward to the one in Barcelona in November.

If you attended the WODC and have more lessons to share leave a comment or reach out in Twitter.

Ana Mingorance PhD

Everolimus, and how rare diseases are reviving the field of epilepsy

In January of 2017, the European Medicines Agency approved everolimus for the treatment of seizures in tuberous sclerosis complex, becoming the first anti-epileptic medication ever approved. But there are more than 25 different molecular entities approved as anti-epileptic medications, so let me explain you why this case is different and why it represents a big milestone for the epilepsy field.

In January of 2017, the European Medicines Agency approved everolimus (Votubia) for the treatment of seizures in tuberous sclerosis complex, becoming the first anti-epileptic medication ever approved. But there are more than 25 different molecular entities approved as anti-epileptic medications, so let me explain you why this case is different and why it represents a big milestone for the epilepsy field.

Epilepsy is a rather common disease, affecting up to 1% of the world population. As a target indication for new medicines it has been extremely successful, with a very extensive list of approved anti-epileptic medications.

The secret to this success lies in the availability of very good animal models and the robustness of seizure counting as primary endpoints. Other neurological diseases with complex cognitive outcomes, for example, have been much more difficult to translate preclinically and to test clinically. Clinical trials in epilepsy are also relatively short, requiring only three months of treatment in general, making the indication particularly attractive for CNS-acting drugs.

But this incredible success reached two walls, and eight years ago, when I started working in epilepsy, I would often hear my colleagues say that the field was dying and that only very few companies were interested in epilepsy anymore.

The first wall is competition. It is hard to add to a field where there are so many treatments available and where many are generic. Most portfolio decisions will therefore favor indications where the return is expected to be superior to the one we can expect in epilepsy, even if the risks are also higher.

The second is drug resistant forms of epilepsy. Since the initial discovery of bromides to treat epilepsy in 1850, about a third of the patients have remained pharmacoresistant. This means that these patients continue to have seizures, despite having tried all of the anti-epileptic medications available and receiving combinations of four or more of these drugs to at least partly reduce their seizure frequency. Newer generation of anti-epileptic drugs improved the tolerability and drug-drug interaction profile of the earlier drugs, but the wall of the pharmacoresistant patients remained.

And ironically, this second wall became the opportunity that would revive the field.

Epilepsy meets rare diseases

A large percentage of patients with pharmacoresistant epilepsy have much more going on than just epilepsy. Many have neurological syndromes where seizures are just one of the symptoms. And these syndromes are orphan diseases, also known as rare diseases, which are those that affect less than 5 in 10,000 people in Europe and less than 200,000 Americans, and that are therefore covered by the Orphan Drug Act and equivalent incentive programs in the large markets.

These incentives have been key to rescue the highly competitive field of anti-epileptic drug development, and in the recent years we have seen a boom in the number of anti-epileptic drugs in development for rare epilepsy syndromes.

Interestingly it first started slowly, with some of the anti-epileptic drugs that were being developed for common epilepsy also being tested and approved for some of the better-known epilepsy syndromes. Two good examples are topiramate and lamotrigine, approved for Lennox-Gastaut syndrome in addition to partial onset seizures and generalized seizures (the two indication approvals for common epilepsy based on main seizure type), or vigabatrin, for infantile spams/West syndrome as well as partial onset seizures.

But more recently we are seeing a growing number of medications being developed for the treatment of seizures only in some rare epilepsy syndromes. And what I find very interesting is that many of these players are not the traditional big pharma companies, but smaller companies that could not go after very large markets due to the demands of large trials and that are now able to afford pursuing these epilepsies because they are orphan size.

This doesn't mean that there were no medications previously available for rare epilepsy patients. These patients are already being treated with regular anti-epileptic drugs, often failing to achieve complete seizure control despite polymedication. In fact, because many of these epilepsy syndromes are so tough to treat, it is not rare to come across a patient that has gone through most if not all of the drugs in the catalogue of anti-epileptic drugs.

What we didn't have are drugs that could be effective in these populations.

And this leads me to my next point…

What the orphan epilepsies need is disease-targeting drugs

There are many medical conditions that will make a person have spontaneous recurrent seizures, which is the definition of epilepsy. Some are consequence of brain damage or malformation, some are genetic, and in many cases the cause in unknown. What they all have in common are seizures, produced by hyperactivity and hypersynchrony of neurons.

Because of the heterogeneity and incomplete pathogenic understanding, epilepsy has traditionally been treated by simply reducing brain hyperactivity. Increasing brain inhibition by acting on the GABAergic system, or reducing excitation with glutamate receptor inhibitors or ion channel modulators, are the main mechanisms behind most of the approved anti-epileptic medications. For a few of the medications, the specific mechanism remains unknown. And collectively they do just that: reduce brain hyperactivity to prevent seizures.

But most rare diseases are genetic, and for many we now know the genetic cause. So these rare epilepsies tell us not only about the problem but also about the potential solution.

A big message every year at the American Epilepsy Society meeting is that we need to develop disease-targeting medications, not just symptomatic ones. Because when we think about what they do, the so-called “anti-epileptic medications” are not such thing. They truly are “anti-seizure” or “anti-convulsant medications”, that treat the symptom that is the seizure. They don’t treat the disease, the epilepsy.

And many orphan epilepsy syndromes, by having a clear genetic cause, open the door to develop the first truly anti-epileptic medications.

Everolimus did just that. And for as much as the whole anti-convulsant vs anti-epileptic debate fills the rooms at the major medical conferences, I have been very surprised to read very little about it after the approval of everolimus for threating epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex.

Everolimus is the first anti-epileptic drug approved, and the significance of this approval needs to be acknowledged and placed in the right historical context.

Everolimus is the first of hopefully many anti-epileptic medications

In January of 2017, the European Medicines Agency approved everolimus for the treatment of seizures in tuberous sclerosis complex, becoming the first anti-epileptic medication ever approved.

Tuberous sclerosis complex is a genetic rare disease that affects many organs but that particularly affects the brain. Like other neurological syndromes, it presents with epilepsy in approximately 85-90% of the patients, intellectual disability and behavioral problems. There is a broad spectrum of disease severity, and receives its name from the formation of tubers (non-cancerous tumors) in different organs.

Tuberous sclerosis complex is the result of hyperactivity of the “mammalian target of rapamycin” (mTOR) pathway due to inactivating mutations in genes that encode the upstream proteins TSC1 and TSC2 in patients. And knowing that cause, hyperactivation of the mTor pathway, also tells us the solution: inhibition of the mTor pathway.

The reason why it has been faster to develop mTor inhibitors for treating tuberous sclerosis complex than similar disease-targeting drugs for other epilepsies is that mTor inhibitors already existed.

Rapamycin is a natural compound first developed as an antifungal agent and later found to be a very effective immunosuppressant. Everolimus is a rapamycin analogue and had already been approved as immunosupresant and for a number of cancers.

In everolimus, Novartis saw not just the possibility of treating one of the tumor types that appear in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (SEGAs), but also of treating other aspects of the syndrome.

I particularly love how Novartis has run separate trials to measure the efficacy of everolimus in treating seizures, intellectual disability and autism associated with tuberous sclerosis complex.

Some times in epilepsy trials, when cognitive endpoints are included, these are secondary safety endpoints to confirm that the treatment does not negatively affect cognition. Such common trial design ignores the fact that most of the genetic epilepsy syndromes have intellectual disability and behavioral problems, in addition to seizures, as regular manifestation of the syndrome. And many of the patients that participate in these trials (and their caregivers) do so in the hope that they will see improvements in these domains, not just in seizure frequency. Running separate trials designed to generate evidence for each of these domains shows that Novartis understands the reality of these diseases, and it is a great example of patient centricity.

The future of epilepsy through orphan epilepsies

Right now, rare epilepsy syndromes are a favorite choice for companies developing drugs with anti-seizure potential because of the smaller trial size, relatively uniform patient population, and market exclusivity when obtaining an orphan drug designation. In most of the cases today, the drugs in development are still symptomatic treatments, just like the many previously approved medications.

For the most heterogeneous and often cryptogenic syndromes, notably infantile spams/West syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, the symptomatic approach that treats seizures without targeting the disease might still be the main approach moving forward. But for the growing number of genetically-defined syndromes where epilepsy is one of the main problems we are likely to see a growing number of treatments developed that target the cause of the disease.

Among these genetically-defined syndromes, the better-known ones and where patient populations are the largest include tuberous sclerosis complex, Dravet syndrome, Rett syndrome and Angelman syndrome. Following the pioneer everolimus, there are already some treatments in development for Dravet syndrome that target the ion channel deficit that causes the syndrome and the seizures (see recent orphan drug designation for OPKO’s antisense therapy).

And behind those, there are multiple monogenic syndromes that also wait for their turn to have an anti-epileptic medication designed for them. For some, like PCDH19, there are already ongoing clinical trials that partly act on the disease biology (see ganaxolone). For others, like CDKL5, there are small investigator-initiated trials to test the potential efficacy of read-through therapies in the subset of patients that carry non-sense mutations.

Other syndromes still wait for the first trial to start. Most have dedicated groups of parents that have created very active patient organizations and that would gladly work with any company that wants to join them in their quest. This includes SCN2A, SCN8A, STXBP1 and so many others, and for some like SCN8A the possibilities to develop disease-targeting medications already looks within reach.

I've provided links to many of the patient organizations for the genetic epilepsy syndromes in case you are a drug developer that wants to get in touch.

As more patients are discovered with these mutations thanks to genetic testing, these syndromes will serve as new orphan indications for companies to get their anti-seizure medications to the market. They are the ones likely to keep the epilepsy field alive, and the patients really need those effective medications – both symptomatic and disease-targeting.

I have had the pleasure of meeting many families of children with many of these syndromes. I’m glad I am meeting them today, and not a decade ago when it seemed that there was little room to develop new drugs for epilepsy. And I’ve met many of these kids and seen very few seizures. What I see the most, and what the families and the physicians deal daily with, are the developmental delays, cognitive disabilities and behavioral problems that are inherent part of all of these epilepsy syndromes.

Because in the end, if a drug really stops all the symptoms there is little difference between a symptomatic treatment and one that targets the disease biology. But in complex syndromes like most of the genetic epilepsy syndromes, there is no such thing as a symptomatic drug that will be able to treat the seizures, the intellectual disability, the motor problems and the behavioral problems.

Because of this, I celebrate the approval of everolimus and look forward to the development of more disease-targeting medications for these epilepsy syndromes. I also look forward to more clinical trials that look at the different aspects of the disease like Novartis is doing with everolimus. This approval, that somehow hasn’t make much noise, is actually a big milestone for the epilepsy field.

And hopefully the first of many.

Ana Mingorance, PhD

Get your free eBook: #ImpatientRevolution

We are one week away from the Rare Disease Day and the global theme this year is Research. To celebrate this day and honor the theme I am releasing the eBook #ImpatientRevolution, a guide for impatient patient organizations.

We are one week away from the Rare Disease Day and the global theme this year is Research. To celebrate this day and honor the theme I am releasing the eBook #ImpatientRevolution, a guide for impatient patient organizations.

You can download the eBook here:

The eBook is free and there is no sign up required. If you want it, it’s yours. All I ask is that if you read it and you like it then help me spread the word so that more patient organizations (or scientists interested) will get to read it too.

For the basic who/why /what questions about the book check out my last entry.

Enjoy!

By Ana Mingorance PhD

Empowering the impatient patient revolution

February 28 is the Rare Disease Day, and the global theme this year is research.

People from all over the world will come together this month to advocate for more research on rare diseases, and to recognize the critical role that patient organizations play in research.

I am excited to join this year Rare Disease Day and announce the launch of my first eBook: #ImpatientRevolution, a guide for impatient patient organizations.

February 28 is the Rare Disease Day, and the global theme this year is research.

People from all over the world will come together this month to advocate for more research on rare diseases, and to recognize the critical role that patient organizations play in research.

I don’t think the organization could have come up with a better theme. I’m a strong believer in patient-centric research. In working with patient organizations who are changing the world. This is why I am excited to join this year Rare Disease Day and announce the launch of my first eBook: #ImpatientRevolution, a guide for impatient patient organizations.

WHAT IS THE eBOOK ABOUT

This eBook is about the many ways patient organizations can shape the research field around their disease and influence the drug industry to work on their rare disease.

I conceived it as a guide for impatient patient organizations – those wanting to accelerate the development of new medicines for their disease by taking an active role. It explains why and how companies develop drugs for rare diseases, and how patient organizations can use this knowledge to analyze their disease field, to identify the main gaps, and to design strategies to get pharmaceutical companies to develop new treatments for their disease.

My wish is to empower patient organizations that want to play an active role in research, and to invite them to take the plunge and join the #ImpatientRevolution

WHAT IS THE AUDIENCE

As a guide, the eBook is written for patients and patient advocates involved in patient organizations. It will be very useful for those just starting or even considering starting a new patient organization, and it will be a good mental exercise too for those that are already part of patient organizations that are active in research.

As a learning resource, the eBook will be interesting for anyone involved in developing new medicines for rare diseases (orphan drugs), in particular if they interact with patients. I myself am a drug hunter, and this is the guide I would have loved to read when I started!

WHO IS THE AUTHOR

I have been a scientist in academia, a scientist in the pharmaceutical industry, and for the last 5 years I have worked as an in-house scientist and advisor for rare disease patient organizations.

While I looked for new ways to help develop more drugs for Dravet syndrome, I also looked at the industry best practices. From this experience I came up with the framework that is the backbone of the #ImpatientRevolution eBook. I have shared these ideas at rare disease conferences and it was time for me to write them down so that I could share them with all the rare disease community. There was not better time for doing this than joining this year Rare Disease Day.

WHEN IS THE eBOOK LAUNCH

The #ImpatientRevolution eBook will launch on February 21, exactly one week before the Rare Disease Day.

I have chosen this date to celebrate the Rare Disease Day, and, at the same time, give time for people to read the eBook so that they get to February 28 more convinced that ever that patient organizations should be at the center of research.

WHAT IS THE COST

You don’t have to pay anything or sign up to any e-mail list to get the eBook. If you want it, it’s yours. All I will ask you is that if you read it and you like it then help me spread the word so that more patient organizations (or families thinking about starting one) will get to read it too.

WHERE CAN I GET IT

The eBook will be available on-line through this website with no payments or sign up required. I will share the link in social media on February 21 so stay tuned!

In the mean time, help me create awareness and spread the word in social media sharing your support for patient organizations playing a central role in research under the theme #ImpatientRevolution

And if you want early access to a copy, just leave me a note in the comments!

Ana Mingorance, PhD

2016 numbers: CNS orphan drugs growing

With 2016 numbers now available, the number of orphan drugs in development for neurological indications is looking quite positive. I have reviewed the numbers of orphan drug designations and approvals by FDA in 2016 to see how popular are neurological orphan drugs today and what the trend is for the near future.

With 2016 numbers now available, the number of orphan drugs in development for neurological indications is looking quite positive. I have reviewed the numbers of orphan drug designations and approvals by FDA in 2016 to see how popular are neurological orphan drugs today and what the trend is for the near future.

The FDA approved only 22 new drugs last year, a big fall from the 45 approvals it granted in 2015. But not all approvals are for new molecules, there are also many approvals that are new indications of previously approved drugs, also known as “drug repurposing”, so the total number of approvals is actually higher than what news outlets otherwise suggest (see here and here).

We see many cases of drug repurposing in rare diseases, so I have looked at the total number of orphan drug approvals and the total number of orphan drug designations in 2016, including new molecules as well as new indications (or designations) for already approved drugs.

THE NUMBERS

In 2016 the FDA approved 37 orphan drugs, out of which only two were for neurological indications: Spinraza (nusinersen) from Biogen for spinal muscular atrophy, and Carnexiv (carbamazepine injection) from Lundbeck for epilepsy as an alternative to oral carbamazepine. The rest of the approvals, as usual, were dominated by oncology.

This means that only 5% of all orphan drug approvals during 2016 were for neurological indications.

However when we look at the drugs that received an orphan drug designation last year the picture is much better for neurology.

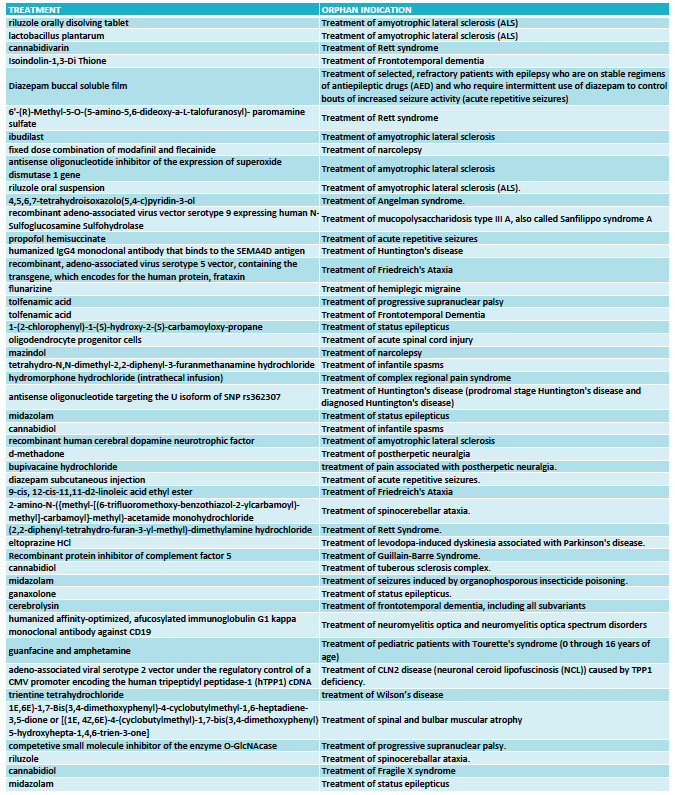

The FDA granted 333 orphan drug designations last year. This number includes some diagnostic reagents so I have only included in my analysis 325 orphan drug designations for the treatment of rare indications. Out of these, 48 orphan drug designations were for neurological indications (see full list at the end of the article) and again oncology dominated in the remaining cases.

With 48 designations in 2016, neurology accounted for 15% of the cases, indicating that the percentage of orphan drugs approvals for neurological indications could triple in the near future.

THE BREAKDOWN

Among the 48 designations, the largest area was neurodegeneration, followed by epilepsy. This reflects two important trends in CNS drug development.

One trend is to target orphan indications when the large indications become too crowded. This is the case of epilepsy, where many of the orphan designations are for drugs that could have efficacy in broader epilepsies -and in many cases are already approved for broader forms of epilepsy- but choose to seek approval for a specific syndrome or type of seizures (such as acute repetitive seizures) to reduce competition.

The other trend is to use rare diseases to obtain the initial clinical proof-of-concept for a compound that is eventually aimed at targeting the large indications. This has became very common in the neurodegeneration field where a Phase 3 failure can cost many hundreds of millions, so de-risking the program in a smaller and more uniform patient population is an excellent development strategy. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) was traditionally the rare disease model for neurodegenerative compounds and had 6 orphan drug designations in 2016, and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) have emerged more recently as attractive rare diseases to re-risk molecules in development for Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease.

What I classified as neurodevelopmental diseases includes the syndromes of Rett, Angelman, Fragile X and tuberous sclerosis complex. I could have classified some of these as epilepsy based on the trial endpoint, like is the case of the orphan drug designation for treating tuberous sclerosis complex with cannabidiol. Likewise, I could classify some of the epilepsy syndromes as neurodevelopmental diseases given the clinical presentation but kept them under epilepsies for this analysis purposes because of the seizure-focused trial endpoints. Collectively, all of these neurological syndromes characterized by seizures, cognitive, behavioral and motor problems are very popular within the orphan drug space.

Among the remaining designations I found interesting 4 treatments for ataxias (Friedreich's ataxia and spinocerebellar ataxia), and two for narcolepsy.

THE FUTURE

Looking at the 2016 orphan drug designations in neurology (see the full list at the end of the article) I can see how rare diseases are facilitating a revival of a field that has suffered from some areas being overcrowded and others being extremely difficult to pursue (think of Alzheimer’s disease). By providing smaller and more homogenous populations rare diseases offer the possibility of shorter and cheaper development programs, opening the field to smaller companies that could now have developed a clinical asset without partnering with a large company. And the genetic nature of many of the rare diseases has also offered us targets that increase the likelihood of succeeding in those trials versus symptomatic approaches in heterogeneous populations.

But not all is opportunistic strategies to reduce competition or de-risk programs. We are also seeing a growing number of gene therapy or antisense approaches in development that target the cause of these rare diseases, including 2016 designations for Sanfilippo syndrome, Friedreich's ataxia and Batten disease and antisense oligonucleotides for ALS and Huntington's disease.

Based on these numbers the future looks promising for neurological orphan drugs, with numbers that could triple and the development of disease-modifying treatments.

Ana Mingorance PhD

FULL LIST ORPHAN DRUG DESIGNATIONS FOR NEUROLOGY - FDA 2016

What marihuana teaches us about drug discovery

There was one clear star at the American Epilepsy Society Annual meeting this year, Epidiolex (cannabidiol). Yet four years ago no one would have thought that the cannabis-derived drug would take over the field of epilepsy in such a big way.

There was one clear star at the American Epilepsy Society Annual meeting last week, and that was Epidiolex. Epidiolex is the brand name of cannabidiol, a drug isolated from medicinal cannabis that GW Pharmaceuticals (Greenwich Biosciences in the US) is developing for the treatment of a number of orphan refractory epilepsies.

Epidiolex was featured in multiple talks and posters, the scientific exhibit hosted by GW Pharma was hands down the most popular one during the meeting, and it was also the main conversation topic in the corridors. It was impossible not to hear about it.

Yet four years ago no one would have thought that the cannabis-derived drug would take over the field of epilepsy in such a big way.

The rise of Epidiolex has been spectacular: during 2016 GW Pharma has announced positive results from three different Phase 3 trials with Epidiolex, with ongoing Phase 2 and 3 trials for other rare epilepsies. Analysts predict peak sales of over a billion dollars. Clearly a very useful drug and a successful commercial product.

The reason why I find the success of this drug such an excellent lesson for drug discovery is that it goes against many of the basic requirements to finance a drug development program:

Cannabidiol is not a new chemical entity, so GW Pharma doesn’t have a patent on the molecule.

As a major medicinal ingredient in marihuana, it is relatively easy for patients to access the plant or extracts without needing to purchase the branded product.

Cannabidiol is only expected to have partial efficacy against the main symptom of these orphan refractory epilepsy syndromes, which is seizures. It does not target the disease and is not expected to provide complete symptomatic relief.

And on top of all that, the mechanism by which cannabidiol is active in epilepsy is still unclear.

If you had tried to approach venture capital firms with a compound that (1) is derived from a medicinal plant, (2) is relatively easy to source as a plant or extract, (3) is likely to provide moderate symptomatic efficacy, and (4) does not have a defined mechanism of action, you would have come out empty-handed.

I know it because I’ve tried this with another molecule having these characteristics.

Investors (and big pharma) want drugs that target the disease biology, with proprietary chemistry and clearly defined mechanisms of action.

What amazes me is that the same investors that would find all those flaws in the investment proposal that I was supporting would turn around and ask me about Epidiolex and its latest results. When confronted with the observation that the very promising Epidiolex happens to have the same profile as our compound the answer was always the same: true, but they have clinical data.

And that’s what this really all boils down to. We create a number of requirements for drugs candidates as a checklist to minimize risks, but once positive clinical data is available that checklist is no longer necessary. We are not short of drugs that target the disease biology, with proprietary chemistry and clearly defined mechanisms of action, that go on to fail in the clinic. We are short of drugs that actually work in the clinic.

Kudos to the GW Pharma team for understanding this and going straight to generating the early clinical evidence that has taken them to where they are today.

Clearly not every drug can be fast-forwarded with multiple parallel trials and very aggressive timelines as GW Pharma has done with Epidiolex. But drugs isolated from medicinal plants offer the unique opportunity to be fast-forwarded to generate clinical evidence as GW Pharma did.

In the case of cannabidiol the breakthrough was the extensive availability of safety data that enabled the company to sponsor multiple investigator initiated INDs and obtain early clinical data. In other cases, depending on the nature of the medicinal plant, it might even be possible to run food safety clinical studies to obtain that early clinical data prior to an IND.

For drugs isolated from medicinal plants, where the primary screening was pretty much done in human patients, trying to enforce the IP and mechanistic standards that we apply to hypothesis-driven drug candidates might make us throw away the baby with the water bath. The success of Epidiolex has only been possible because GW Pharma was well-funded and had the vision to ask the right questions.

If clinical data is the main deciding factor, then maybe investors should first ask if a compound has a quick path to be tested in patients. For those compounds where the answer is yes, such as in medicinal plant-derived compounds or repurposed drugs, the priority should be in designing a quick clinical study able to generate that early clinical evidence. For those compounds where the answer is no, then we might continue to use checklists to try and minimize risks prior to any clinical study.

When we ask about the possibility to generate quick clinical data, drugs coming from medicinal plants or repurposed assets, where safety has been established, suddenly become exceptional opportunities.

I don’t know if investors will be able to look at Epidiolex and reconsider what they ask to early candidate drugs. I, for one, will make sure to tell them the story of what marihuana has taught us about drug discovery and about asking one key question: does this compound offer a possibility to generate quick clinical data.

Let me know what you think about it in the comments.

Ana Mingorance PhD

Originally published in LinkedIn on December 16 2016

How close are we to creating transgenic people?

The journal Nature just released one of the most anticipated breaking news of the last few years: CRISPR gene editing has been tested in a person for the first time. In my day-to-day work I interact with families that have a child with a genetic disease. I get one question a lot: how close are we to turn that discovery into a therapy for people with genetic diseases?

The journal Nature just released one of the most anticipated breaking news of the last few years: CRISPR gene editing has been tested in a person for the first time.

In my day-to-day work I interact with families that have a child with a genetic disease. These are diseases where the mutation is produced “de novo”, which means that it happened during the production of the baby. The family didn’t carry any mutation and most likely that child is the only one with that exact mutation, or one of a handful world-wide.

As you can imagine, ever since scientists announced they had found a way to do copy-and-paste in DNA to introduce or to correct mutations I get one question a lot: how close are we to turn that discovery into a therapy for people with genetic diseases?

And despite the breaking news from Nature the answer is still “not that close”.

Let me elaborate on that.

Before being available as a treatment for people born with genetic mutations the CRISPR technology needs to go through roughly four steps:

Show that CRISPR can correct mutations in human cells in a test tube. This was the groundbreaking discovery that got us started in an amazing medical development explosion.

Show that these genetically-modified cells can be delivered to patients. This is more cell therapy than gene therapy and it is very useful on its own. Likely to be the first path forward for the CRISPR approach.

Show that we can actually correct mutation in patients using CRISP. Now we are talking about gene therapy, and for years this will have to be done in clinical trials under controlled conditions.

Finally, get approval for gene therapy using CRISPR technology so that we can fix patient’s mutations, effectively creating transgenic people.

What Nature announces is that scientists at Sichuan University have treated a patient with lung cancer with cells that had been reprogrammed using CRISPR before being delivered into the patient. This is step 2.

It had also been done before using other technologies that enable gene-editing, also in diseases where scientists first modify those cells outside the body and then deliver them to the patient, such as in cases of leukaemia or HIV. CRISPR is predicted to be the most powerful (and easy!) of these methods and is likely to be the one that will become a real treatment so reaching step 2 is great news.

At this second stage, these are all “ex vivo” approaches where the gene editing technology is applied to the cells that will be used to treat the patient, instead of using the technology directly in the patient.

The move towards step 3, editing the patient DNA, opens serious safety concerns:could the gene-editing enzymes cut and paste more letters in the DNA that they were intended to? Could they cause unwanted mutations? Because of that, it is likely to happen first in very localized indications such as tumours or retinal disease.

Moving from those localized diseases to more widespread ones will have the same challenges to reach the target organs that “traditional gene therapy” currently has. For the non-initiated, “traditional gene therapy” doesn’t change the patient DNA, instead it uses virus that have been stripped of the virus DNA to infect the patient and deliver a healthy version of the gene that the patients have mutated. At the end the patient has his own genes plus this new therapeutic gene. And that is not easy to do in hard-to-reach organs such as the brain!

Because delivering the CRISPR enzymes will also rely on viral vectors, even if CRISPR was proven today to be totally safe we wouldn’t know how to apply it to the brain tomorrow, since we still haven’t mastered that delivery aspect yet.

For any patient with a neurological condition caused by de novo mutations (so mutations unique to him/her) this is how the things to do list looks like before we can treat him:

CRISPR needs to be proven safe in small regions (step 3)

We need to find good viral vectors to deliver genes to the brain, which is larger than the eye or blood cells and happens to come inside of a hard box.

Those viral vectors also need to be safe.

CRISPR will be first used for genetic neurological diseases that are inherited, which means where the same mutation is found in many people.

And only after all that has happened we can think of using CRISPR therapy when the target mutation is unique for each patient, which introduces additional questions: can we get approval for the disease and just change the target sequence that the CRISPR uses? Will companies ever manufacture separate ones for individual patients? etc

So for the patients I work with, who carry de novo mutations that cause neurological diseases, the answer to how close we are to use CRISPR as a therapy for people like them can only be “not that close”. These are probably the last diseases to benefit from the gene editing technology.

In the mean time we celebrate that we have reached step 2 with CRISPR, delivering edited cells to a patient, and keep our eyes on that next frontier: the in vivo experiment, the first patient that has his own DNA corrected using CRISPR in a clinical trial, the first transgenic people.

Let me know what you think about it in the comments.

Ana Mingorance PhD

Originally published in LinkedIn on November 16, 2016

You are unique, and medicine knows it

When a doctor prescribes you a medication you will be in one out of four groups of patients: 1) you might have experience and no side effects, 2) you might experience efficacy with side effects, 3) you might not have efficacy nor side effects, or ...

When a doctor prescribes you a medication you will be in one out of four groups of patients: 1) you might have experience and no side effects, 2) you might experience efficacy with side effects, 3) you might not have efficacy nor side effects, or 4) lucky you! you might have no efficacy yet suffer from side effects.

And your doctor cannot know in which of the four groups you will be before prescribing the medication. That’s life! And that’s medicine today for most people.

But healthcare is changing very fast, and one of the biggest transformations is a change in focus from treating populations to treating individuals.

These are the three big trends you should know that are transforming medicine from treating many to treating you:

Trend #1: rare diseases are “in”

I’ve been working with rare disease patient organizations for the last 5 years and in this short time I have witnessed how collectively rare diseases have gone from being the awkward cousin that few people wants to talk to at a party to being the focus of most presentations at pharmaceutical conferences.

The FDA first released the Orphan Drug act to incentivize the development of drugs for rare diseases (orphan drugs) back in 1983, so it is not new to grant them designations and special treatment in the drug development process. What is much more recent is the increased focus by the pharmaceutical industry due to a combination of financial, research and technological factors.

Financially, it has become unsustainable for most companies to run clinical trials for common diseases. As we have been successful at developing medicines for some of the common diseases, the low hanging fruit is taken and we are left with some extremely complicated areas such as neurology and psychiatry where clinical trials are not just enormous but also likely to fail in most cases. Only a few big companies have the luxury to face the monster.

And on the research and technological front, the industry has now gained much understanding of the genetic and molecular basis of many diseases, guiding the development of new drugs (target-based) and making feasible the optimization of such drugs (high-throughput screening).

Because most rare diseases are also genetic, they now represent the ideal initial indication in which to test an experimental medicine before jumping into larger, riskier and more expensive diseases.

Rare diseases are the stepping stone, the gateway to larger indication, and in the case of smaller drug discovery companies, rare diseases are also a legitimate area of focus where they can develop medicines without needing to partner with large pharma. Win-win territory.

All these trends means good news if you have a rare disease, because there has never been a time better than now for rare diseases to attract the interest and the funding from the pharmaceutical industry.

Trend #2: Personalized medicine

We already knew that not everybody responds well to the same medications. What we didn’t know was how to predict if you would be a good responder or not to a new medication before trying it on you.

But technology, and in particular genetics and bioinformatics, have made it now possible in some cases to match the best drug with the best patient.

The oncology field was one of the first ones to step into this territory that is known as personalized or precision medicine. Initially patients where treated based on where the cancer has started, such as the lungs or the ovaries. By after noticing that cancer can result from a number of genetic mutations and developing medicines for the most common mutations we can now match those patients with those drugs regardless of where the tumor first started in their bodies, saving many more lives.

In his 2015 State of the Union address, President Obama announced the Precision Medicine Initiative to revolutionize how we treat diseases with the goal to being able to tailor specific treatments to the unique characteristics of the patient, moving away from a one-drug-fits-all approach. This was not the first step in that direction but it certainly was a landmark that made the personalized medicine official and will hopefully also provide the funding necessary for such a groundbreaking challenge. Next step is not treating diseases but treating patients.

We are definitely entering into an amazing period in healthcare that will transform how we understand and treat diseases.

Trend #3: Pay only if it works