TOP 5 INSIGHTS FROM THE AMERICAN EPILEPSY SOCIETY MEETING 2023

I often write a summary of the main lessons from the American Epilepsy Society meeting, but for a second year there was so much about rare epilepsy syndromes or DEEs that I was not able to follow the main conference. I only went to one lecture session, and focused instead on the posters, scientific exhibits and meetings, which are all the opportunities to directly talk to people and by far the main value of this congress.

This is my summary of the trends that I am seeing in rare epilepsy syndromes after attending AES 2023. It is not a summary of the conference itself, which has really become too large to cover. In particular, I wanted to see if 2023 delivered on the promise set last year, which was Escape velocity for genetic epilepsy syndromes.

1 – EPILEPSY AS A COLLECTION OF RARE DISEASES

The larger pharma space has experienced a clear shift towards more personalized medicine and more orphan drugs. And epilepsy is not an exception. Since around 2014 with the clinical trials of cannabidiol, we have seen an explosion of programs directed to epilepsy syndromes, both with symptomatic and with gene-targeted approaches.

At AES 2023 I attended the plenary session where Dr Kelly Knupp from Children’s Hospital Colorado showed one slide with a key title, which ended up getting very popular on social media. It read: “Epilepsy is a collection of Rare Diseases”.

I believe this probably holds true for all medical fields, where as we gain insights into the cause (etiology) of diseases we realize that one large disease is actually many orphan-size diseases all sharing some common phenotype. But it is important to talk about this, and it was important to hear this message in the large session, because it captures where much of the attention right now is going within the epilepsy space: to the rare diseases.

And this was particularly visible at AES 2023, where many of the pharma stands at the exhibit floor and pharma-sponsored sessions focused on rare epilepsy syndromes. As last year, this was largely focused on the most famous syndromes: Dravet syndrome, LGS and TSC; and this year also included CDD, the 4th rare epilepsy syndrome with an approved treatment, and the subject of an additional Phase 3 trial by UCB pharma.

Yet the poster session gave us a glimpse into the future, and I would like to highlight a poster from Biogen on KCNT1 and two from UCB on STXBP1 and SLC6A1. Although all preclinical, these posters are important because they illustrate how the large companies are now proactively working on the genetic epilepsy syndromes, not just watching the field (as they did at first) or buying the orphan drugs developed by others (more recently). This is an important step for the industry.

With large biotech and pharma now on board with genetic epilepsy syndromes, we are reaching a more mature stage in that transition from only working on seizures to also working on genetic causes. And this is happening without taking attention away from the larger seizure treatment space, where I would highlight the impressive results with XEN1101 so far in focal-onset seizures and potential also for generalized seizures. This is a very good scientific time for the epilepsy drug treatment space in general.

2 – RARE EPILEPSIES AS A TRANSITION POINT IN THERAPY DEVELOPMENT IN EPILEPSY

Are rare epilepsy syndromes the future of epilepsy treatment? Not at all. The syndromes are rather a natural step in the transition from symptomatic treatments to treatments that treat the cause of the disease.

I really liked a presentation by Dr Gemma Carvill from Northwestern about the history of epilepsy. She highlighted how most of the progress so far has been not on efficacy (we always hit that 30-35% of refractory patients) but on having better tolerability, and how more recent development focused on rare epilepsy syndromes, then on genetic treatments for these syndromes, and how the future direction is to use those technologies to treat epilepsy at large. When applied to the non-monogenetic epilepsies, the main approaches would be gene regulation approaches, moving up or down the expression of important targets, instead of activating or inhibiting proteins as small molecules often do.

Important advances to modulate gene expression in epilepsy are dCas9 approaches (for example Colasante 2020), the use of activity-dependent promoters (for example Qiu 2022), or the targeting of non-coding RNAs (reviewed in Stine 2023). And one of the best examples of going beyond the rare epilepsies is the AMT-260 gene therapy program from uniQure for Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Gene therapy trials are not only for monogenetic epilepsy!

So genetic epilepsy syndromes are not the ultimate destination, but the first application of a new way of treating epilepsy, and this is becoming more clear as the epilepsy field evolves.

3 – PRESSURE IS HIGH, ALL SYNDROMES NEED BETTER TREATMENTS

Dravet syndrome is one of the epilepsy syndromes that has received the most attention from the industry. It has three drugs approved, soticlestat in phase 3 trials, and is the target of the most advanced clinical trial with a therapy designed to correct the cause of an epileptic syndrome: the ASO STK-001 from Stoke to correct the haploinsufficiency in SCN1A. This makes Dravet syndrome the “lucky syndrome”, and I have even seen grant proposals for Dravet turned down because it was considered “already done” by reviewers.

Yet at the Dravet syndrome roundtable we got to hear about 6-year old Anna and her journey with Dravet syndrome from her grandpa Ted Odlaug, who is the current president of the US Dravet Syndrome Foundation. During her short life, Anna has tried multitude of anti-epileptic drugs, including the three approved for Dravet syndrome, yet her epilepsy has gotten worse and worse and she currently has no days without seizures. She also has the cognitive development of a 2-year old, limited vocabulary, and her high seizure frequency including nocturnal seizures place her at very high risk for sudden death (SUDEP). Yet she got the “lucky syndrome”, the one with the most advances towards treating the symptoms and the cause.

This is something important to hear and to remember. All of what we have in epilepsy syndromes are some treatments approved to treat seizures, which work in SOME patients and that are tolerable by SOME patients. The treatments to correct the cause of these diseases are still in early development and still only accessible in the context of clinical trials. And this holds true even for the “lucky syndrome”. Most other syndromes are still behind in terms of therapy development.

So there is a big gap between the science, where we have cured the mice with SCN1A deficiency with several gene therapies and ASOs, and what patients in the real world like Anna have access to. Why is there such a progress gap between science and patient care? Part of it is time, treatments simply take years to get from the lab to the market, but we are also facing challenges bigger than time. And we are seeing these additional challenges as the first disease-targeting programs make their way to clinical trials and progress slows down. I discuss this in the next section. For this section my main message is that all syndromes need better treatments, and that none of them is yet “done”.

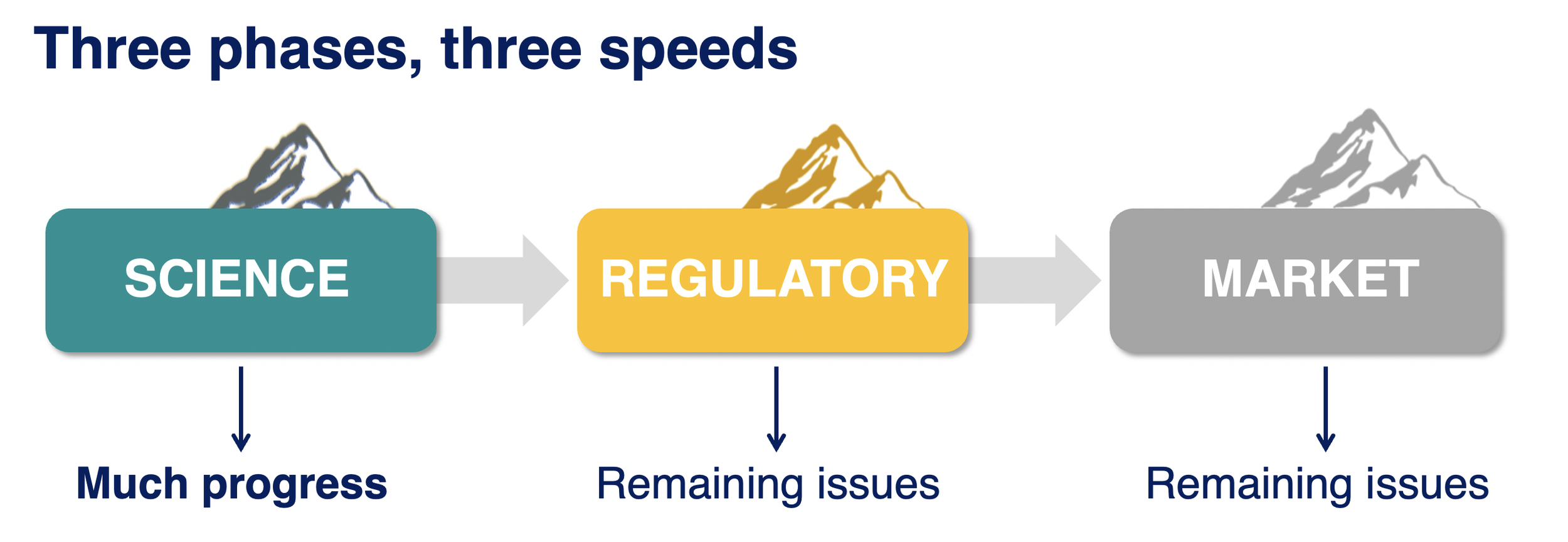

4 – RARE DISEASE THERAPY DEVELOPMENT HAS THREE MOUNTAINS TO CLIMB

Do you know the metaphor of a climber struggling to climb a mountain only to reach the summit and realize that there are other mountains just as high behind it? I believe this is where we are right now in developing disease-targeting treatments for genetic epilepsy syndromes, we are getting to the summit of that first mountain and looking at the next two. It turns out that getting gene-targeted treatment to trials was just the first mountain.

We had many discussions about these challenges during AES 2023. In fact, this was probably the most common topic across my many discussions with other attendees.

Mountain 1: Science.

Science has been advancing quite well. There are many preclinical programs with gene therapies and ASOs ongoing for a growing number of epilepsy syndromes, and we start having clinical trials. This year we have seen newer data from Stoke showing that with the highest dose of STK-001 they can have profound seizure reduction in patients with Dravet syndrome, and that even with moderate doses they can see improvements in non-seizure domains like communication. And Praxis has also started clinical trials with another ASO, PRAX-222, this one to reduce SCN2A in patients with gain-of-function mutations. This is in addition to Praxis’ small molecule trial for SCN2A and SCN8A gain-of-function DEEs.

We have also seen this year hopeful clinical trials results in Angelman syndrome (Ultragenyx) and Rett syndrome (Taysha) that make us all very hopeful that the neurodevelopmental field is getting closer to true disease-modifying treatments. So overall we start seeing the transition from preclinical ASO and gene therapies to clinical trials. This is just the first mountain.

Mountain 2: Regulatory.

This is a difficult one. We are still not sure how to design a clinical trial to show the difference between correcting the gene versus treating the seizures, and there are no precedents for a broader label to treat the disease (all we have are approvals “for the treatment of seizures in syndrome X”).

The patient community, clinicians and the companies developing treatments to target the cause of the epilepsy syndromes are working to solve this challenge by running observational clinical trials to validate non-seizure outcomes and endpoints.

The most advanced studies are the ones on Dravet syndrome by Stoke and Encoded, that have documented how, for example, the number of seizures in Dravet syndrome remains constant over time (up to 2 years!) as a group average. So while one patient might get better or worse, if you run a trial the number of seizures should balance out and remain stable. Many other symptoms are also stable or improve just a little, which will help us interpret open-label studies that may show improvements. And there are also other endpoint-enabling observational studies going on for CDD, SYNGAP and STXBP1 (at least) that I know.

We still don’t know which of these scales will be useful in clinical trials to show improvements beyond seizures, or how to convert the scales into specific endpoints, but in the meantime some of the companies with approved drugs to treat seizures in DEEs are leaning quite far into almost claiming efficacy in non-seizure outcomes by relying on caregiver surveys. And this is a development that worries me. We already have the problem in rare diseases of having to overrely on case studies due to so few placebo-controlled trials. And now we are adding the problem of companies with anti-seizure medications using caregiver surveys not reviewed by regulators to talk about improvements in behavior and cognition. This was particularly visible in 2023, and it almost creates two tracks with different burden of proof for non-seizure outcomes: one of post-approval caregiver surveys for small molecule anti-seizure drugs, and one of years of endpoint-enabling studies followed by year-long trials with not-yet-validated outcome measures for ASO and gene therapies. I’m not liking this development.

Mountain 3: Market.

A common challenge for rare diseases is not having enough patient numbers for an attractive return-on-investment. We have seen this addressed in rare epilepsy syndromes by developing the same molecule for a group of rare diseases. For example Epidiolex approved for Dravet, LGS and TSC; Fintepla approved for Dravet, LGS and in Phase 3 trials for CDD; and soticlestat in Phase 3 trials for Dravet and LGS. But running multiple parallel trials is expensive, so companies focus only on the largest syndromes.

A near-future regulatory innovation might be clustering syndromes into a broader label for drug development. This year we heard from the company Longobard, with a Phase 2 basket trials in DEEs, that they will consider discussing with regulators the potential to keep the combined DEE target population for Phase 3 trials and approval. I see regulatory challenges to do this but I also see it as the only way to get clinical trial data for many of the DEEs beyond the top 6 or so in terms of patient numbers, so I would love to see this happen.

The company Tevard is also considering a combination of DEEs, in their case because they are developing a gene therapy to help the cell skip premature stop codons caused by non-sense mutations, so their case is very similar to basket trials in the cancer field. In the case of Tevard, the target population would be genetic DEEs caused by non-sense mutations, and the common primary endpoint could be reduction in seizure frequency so one trial could test them all. Even a clinician working for Jazz told me that they had been asked by many clinicians to run studies with Epidiolex in groups of biologically-related DEEs (for example ion channels, or synaptopathies) so this definitely seems to be a conversation that we are hearing loudly in 2023 and that will likely turn into action.

5 – IMPRESSIVE PATIENT GROUPS

I have been working on rare epilepsies and supporting patient groups for 12 years now. And oh boy has that changed. Patient advocacy in 2023 is much more advanced and professional than how it was back in 2011.

The four epilepsy syndromes that have drugs approved all have very impressive patient-run foundations and patient groups behind them. See for example how the AES 2023 Extraordinary Contribution Award went to Mary Anne Meskis, Executive Director of the Dravet Syndrome Foundation. But they are no exception anymore. During AES 2023 I had a chance to interact with some of the patient groups for syndromes that still have no treatment approved (or advanced clinical trials) that were equally impressive.

Some of these deserve a shout out:

I attended the SYNGAP conference by the SynGAP Research Fund the day before AES. I wrote a separate summary about this conference, but this group is amazing in how they are tackling the key challenges to therapy development in their field, scientific/medical/industry community building, and patient mobilization including a very international footprint.

I caught the end of a meeting between the FamilieSCN2A Foundation and a biotech company, since I was next to meet with the company, and I was very impressed with their print slide-deck summarizing all of the resources and learnings from the SCN2A field. This included the entire list of mouse models and efforts to also validate outcome measures, for example in communication. This will help companies get up to speed with SCN2A quickly, and I’m pretty sure it will help start treatment programs by making it easier to choose this syndrome.

It is a tradition for me to sit down with Charlene and John from the STXBP1 Foundation every year at AES and compare notes about their field and the syndromes that I am working on. This year Charlene showed me one slide with the STXBP1 pipeline in 2019, having only one program for potential repurposing with nothing else on the horizon. And then the 2023 pipeline slide, with 11 programs in development including several gene therapies being developed by companies. Talk about progress!

CONCLUSSION: HAVE WE REACHED ESCAPE VELOCITY?

In science: yes. We are seeing a growing number of ASOs and gene therapies being developed for several of the neurodevelopmental syndromes with epilepsy. Transition to clinical trials is still a bit slow but the progress across many diseases is notable.

In regulatory path and market conditions: no. We are still not sure how to design a clinical trial to show the difference between correcting the gene versus treating the seizures, there are no precedents for a label that goes beyond seizures, and the market is still a limitation, leading to companies always choosing the largest syndromes and neglecting the other hundred or more.

We are seeing some development to address these challenges. Some are good developments, like considering how to get several syndromes into a single clinical program and approval. Some are (as I see them) bad developments, like companies promoting cognitive and behavioral efficacy for their drugs using a language identical to the one they use for seizure efficacy, which is the only one approved and on label.

Another development is the arrival of gene therapies to non-genetic epilepsy trials, which is very promising. Also exciting is to see big bio and big pharma proactively working on the genetic epilepsy syndromes, not just watching the field or buying the orphan drugs developed by others. And we are also now getting the results of the observational studies that are being carried out for several DEEs to identify endpoints for more complex clinical trials. So overall this was a good year.

For 2024 my hope is to:

see some answers to the regulatory challenges, with learnings from Stoke and also from other companies in the neurodevelopmental (non-epilepsy) field.

see more clinical trials started with treatments targeting the cause of the disease (potentially from the group of SLC6A1, SCN2A Loss-of-function, and CDD?)

see more mouse proof-of-concept data with treatments targeting the cause of the disease. We have many ideas and in vitro data, but not enough clinical candidates yet.

And I hope to see that in Los Angeles, for AES 2024.

Ana Mingorance, PhD

Disclaimer: These are my own impressions from the presentations and topics that I was most interested in. I write these texts with the parents of individuals with rare epilepsies in mind, so excuse also my lack of technical accuracy in parts.