Epilepsy Insights

What I learnt at the SYNGAP Conference 2023

These are my main learnings from the Syngap Conference 2023 celebrated in Orlando the day before the American Epilepsy Society meeting.

Last year I attended the Syngap Conference organized by the SynGAP Research Fund the day before the American Epilepsy Society (AES) meeting. It was fantastic, but I did not write a separate summary for it, only a mention as part of my AES summary. But then this year I attended again the Syngap Conference, again the day before AES 2023 started, and I believe it deserves a separate summary. So here it goes: these are my main learnings from the 2023 Syngap Conference about the SYNGAP research and therapeutic field.

1 – COOL AND SCARY NEW BIOLOGY

There was a lot about the biology of the SYNGAP1 gene and the SynGAP protein at the conference. The main learnings that stayed with me are two:

Did you know that SynGAP seems to control cytoskeleton (the cell skeleton) and in particular the primary cilia? This is like a special part of the neuron that looks like a short tail. This is interesting because I work very much in CDKL5 deficiency disorder (another neurodevelopmental syndrome with epilepsy) and CDKL5 is also doing the same things!! This whole “cilia connection” is very cool and also very puzzling. I don’t know what to do with this information, but it seems that proteins that evolved to control the cell skeleton and that special primary cilia might have also evolved to control synaptic remodeling and that is why we get neurodevelopmental syndromes with epilepsy when they are mutated. Helen Willsey from UCSF was such a great speaker! One of the highlights of the conference.

That was the cool new biology. The scary new biology is that we learnt that syngapians spend in REM sleep only half of the time that other people do. REM sleep is when we dream… so having SYNGAP steals the dreams of the kids, and this is very sad. The good news is that REM sleep could be a biomarker for these kids.

2 – HELP OUR KIDS NOW: DRUG REPURPOSING

There were several talks about drug repurposing, which means seeing if there could be already something sitting at the pharmacy shelf (perhaps even in the supplement shelves) that could help syngapians today. Repurposing is the search for faster treatments while investing in the long term disease-modifying treatments.

We learnt about a research program by Rarebase using patient-derived neurons to characterize some potential drugs that may help increase the mRNA of SYNGAP1 (remember that there is one good copy of the gene that we can use to get more protein), and one in fruit flies missing SYNGAP1. The mutant flies have small eyes looking disorganized, which serves a read out to look for drugs and supplements that could fix their problem and therefore compensate for lack of SYNGAP1. The researcher, Clement Chow, explained that they are finding many drugs that come up as positive and that have similar action, like many anti-inflammatory drugs, so the results are looking promising. And we also heard from Zach Grinspan who has been running a repurposing trial in SLC6A1 and STXBP1 with a drug called phenylbutyrate that will also be tested in SYNGAP. This talk opened a very interesting debate about this type of repurposing trial. For example: do we need a consensus to pick the winner compounds? How are we going to test the potential repurposing drugs if they are already available for example at CVS? Should we go through 6 months of paperwork just to have ethical approval and spend much money on trials or go ahead and try it individually? And how would we learn from those N-of-1 family-run studies?

Prof Ingrid Scheffer, who is one of the most famous doctors in the rare epilepsy space, insisted that the only way to know if something works (and is safe) is to run randomized controlled trials, and that the burden should be in the companies that own those drugs, not on the patient groups. This was a great debate!

3 – THERAPIES TOMORROW: HIGHWAY TO CURES

To cure a disease like SYNGAP we know very well what we need to do: help neurons make more SynGAP. I moderated this session with the message that “we have all of the ingredients that we need to fix SYNGAP”: we know the cause, we have one good copy of the gene to use, the disease is not degenerative, the animal models are good, and the animal models indicate that the disease is likely reversible. We are also talking about a relatively large rare disease, with a very strong patient community working on solving the right problems, and there are already several companies working on treatments.

We had a presentation from Praxis and one from Stoke, both working on ASOs to boost SynGAP production using the good gene copy. In both cases, these companies have more advanced ASO programs for other epilepsy syndromes so we will get to use those learnings for SYNGAP. And we also had a presentation from Tevard, a company working on a gene therapy to help neurons skip premature stop-codons caused my non-sense mutations. Tevard is planning to run clinical trials with this gene therapy in a selection of genetic epilepsy syndromes including SYNGAP, and they are ready to start safety studies in non-human primates next year to then progress to clinical trials.

I also know that there are more therapies being developed to target the cause of the disease, and some of those companies where present in the room although they didn’t give a talk, so therapies are coming.

And to prepare the field for those therapies the community is running A LOT of clinical studies to know the natural history of the disease and possible outcome measures (scales) to use for trials. A LOT. This included a disease concept model, the Ciitizen study, and an excellent endpoint-enabling study at CHOP that is designed the same way that companies design their observational studies, this is top quality. Also a lot on biomarkers. What I wonder is how to integrate all these data. What is clear is that with so much work this is not a road to trials, but a highway to trials, in particular the trials for disease-targeted treatments (the cures).

4 – THE KEY CHALLENGE OF MISSENSE CAN’T WAIT

The disease that we often call SYNGAP for short happens when one of the two copies of the SYNGAP1 gene is mutated, and this mutation sometimes breaks the future protein (non-sense, frame-shift, truncation, deletions) but sometimes the mutation makes a protein that has one wrong letter. This is not trivial, and read this section until the end to know the mind-blowing implications. This means that many SYNGAP patients have a mutated protein instead of a missing protein. What if we can fix those? Maybe they just need a bit of help with folding. What if they stay around and don’t let the good proteins work? Then we need a strategy to remove them. This is why there are several programs trying to understand what happens to those mutated proteins, which are often unique to each patient with a missense mutation. This includes in silico modeling and also in vitro real experiments.

But the biggest implication is perhaps not for treatment, but for diagnostics. We learnt from Gemma Carvill that genetic labs often don’t know how to interpret these changes of letter, so patients receive a genetic report for “VUS” or Variant of Unknown Significance. With a VUS you cannot be diagnosed, because maybe the gene is totally fine (we all have some different letters here and there in our DNA that are harmless). In SYNGAP1 gene sequencing for patients with epilepsy, the large majority are VUS, like 80% or so, so they don’t get a diagnosis. The other 20% is split between benign (trivial) mutations, and pathogenic which are the real SYNGAP. But then Gemma and her colleagues train a computational model to predict if a missense is bad or trivial, they found out that about 22% of the VUS are likely pathogenic mutations. What this means is that if we could solve the meaning of the missense mutations, the diagnosed patient population with SYNGAP could multiply by 3 or so. This has mind-blowing implications, not only to grow the patient population but to then help those new patients access better treatments and clinical trials and a community of families like theirs.

No wonder this is such an important priority for the SynGAP Research Fund!

5 – ALL FOR ONE

A real team

I am used to seeing patient groups focused on one country or territory, even when they call themselves international. This is understandable. I am a Spanish scientist, so I often collaborate with the groups in Europe (proximity and shared regulatory framework) and in Latin America (shared language and culture). And what I love about the SynGAP Research Fund is that it integrates all those worlds. You could even see that in the logos in all the conference materials:

SynGAP Research Fund

SynGAP Research Fund EU

Fondo de Investigación de SynGAP

And you could also see it around the room, because this group is very international. We had Mike and Aaron and Hans and Sidney and Lauren and others from the US, and Vicky and Martha and Carlos Caparrós and others from Latin America, and Katrien and Virginie and likely others from Europe. This is a true international team and this is exceptional and wornderful.

Get treatment for everyone

A message that was heard multiple times during the scientific program was the concern for all families living with a syngapian:

The focus on repurposing was: how can we get these treatments to everyone?

The focus on missense was: how can we find all those missing families so they are not left in the dark?

The joint work of the different territories US/EU/LATAM is also about getting to everyone.

Mike Ganglia closed the scientific conference with the words “what are all the people out there doing with their non-diagnosed syngapians?! We owe it to those parents”

A unique community

Clement Chow (the fruit fly scientist) explained that “Mike found us on Twitter, where all beautiful relationships start”, referring to Mike Graglia. And now Clement is working on finding repurposing candidates for SYNGAP!

My own path to get to know this community was similar. I was invited to give a talk in San Diego in 2018, and a SYNGAP dad reached out to me also through Twitter and asked me if I would like to meet his son with SYNGAP and his family while I was in town. That was Aaron, Jaxon’s dad, and it is a very good strategy to get scientists to get interested in a rare disease.

These two stories are an example of the proactivity of the SRF and the SYNGAP patient community, and other quotes that I wrote down during the 2023 conference also communicate this same message:

Tom Frazier, who is developing web-based measures of behavior and cognition: “This community volunteers for studies more than any other”.

Clement Chow: “[…]the strength of foundations leading the therapeutic discovery for rare diseases right now, and this foundational machine is best oiled than any other foundation that I have worked with, you should be proud of it”.

Then the following day was the Families Day with I believe more than 40 families attending and even using the opportunity to collect clinical data for some of the research studies. This community is exceptional and ready to partner and drive research forward.

* * * * * *

I hope you enjoyed this summary. If you are a SYNGAP family member, try to join us next year in Los Angeles right before AES 2024, there is also a second day focused on families after the scientific day. And if you are a scientist or clinician, please also come to LA one day early. This disease has all of the ingredients that we need to fix it, and a unique community behind it. Please join.

PS: my summary from AES 2023 is HERE

TOP 5 INSIGHTS FROM THE AMERICAN EPILEPSY SOCIETY MEETING 2023

The American Epilepsy Society (AES) meeting is the largest epilepsy meeting of the year, and because it takes place every month of December it also serves as an annual review on the understanding and treatment of epilepsies. These are my top 5 insights from the American Epilepsy Society 2023 meeting.

I often write a summary of the main lessons from the American Epilepsy Society meeting, but for a second year there was so much about rare epilepsy syndromes or DEEs that I was not able to follow the main conference. I only went to one lecture session, and focused instead on the posters, scientific exhibits and meetings, which are all the opportunities to directly talk to people and by far the main value of this congress.

This is my summary of the trends that I am seeing in rare epilepsy syndromes after attending AES 2023. It is not a summary of the conference itself, which has really become too large to cover. In particular, I wanted to see if 2023 delivered on the promise set last year, which was Escape velocity for genetic epilepsy syndromes.

1 – EPILEPSY AS A COLLECTION OF RARE DISEASES

The larger pharma space has experienced a clear shift towards more personalized medicine and more orphan drugs. And epilepsy is not an exception. Since around 2014 with the clinical trials of cannabidiol, we have seen an explosion of programs directed to epilepsy syndromes, both with symptomatic and with gene-targeted approaches.

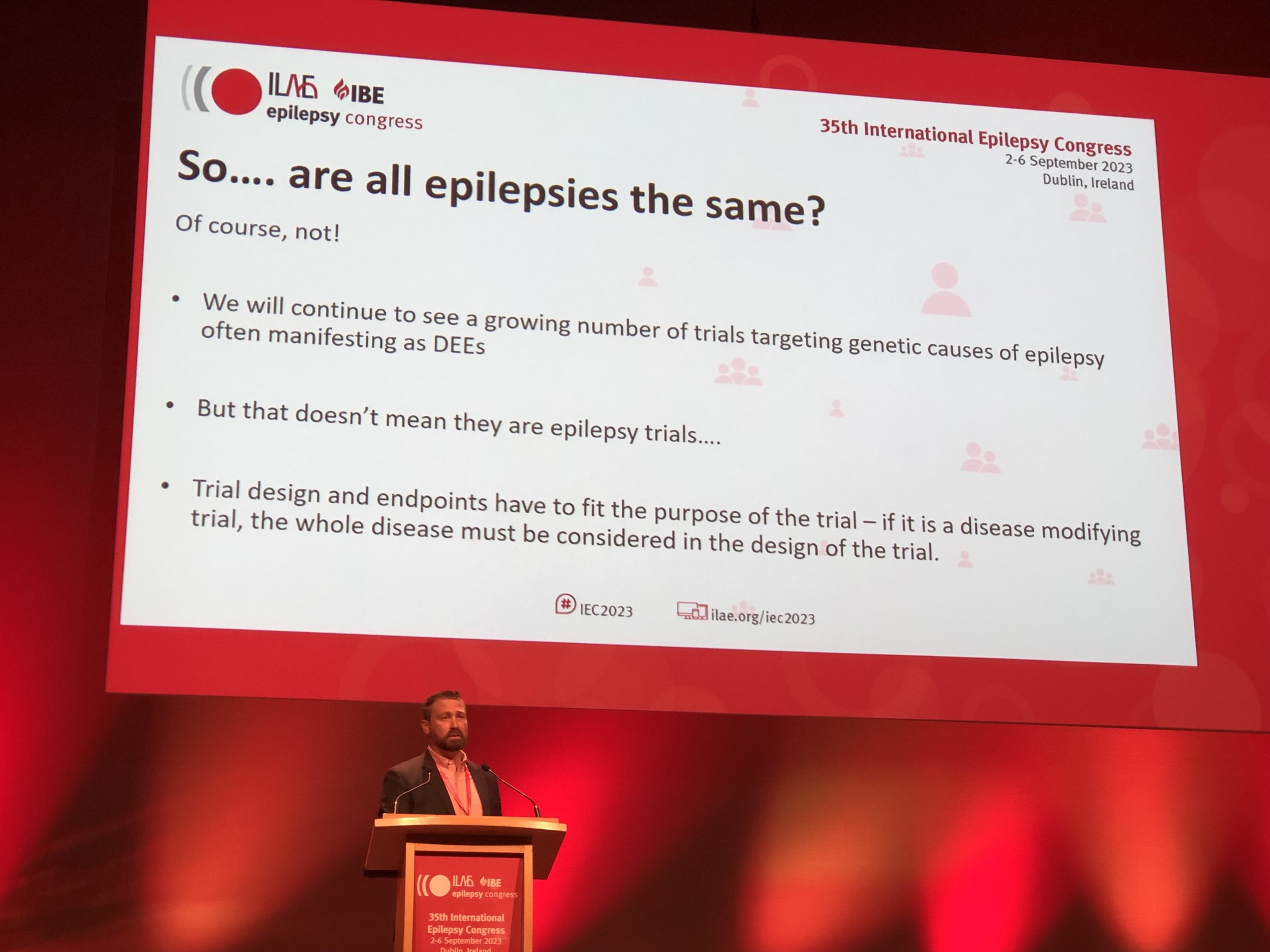

At AES 2023 I attended the plenary session where Dr Kelly Knupp from Children’s Hospital Colorado showed one slide with a key title, which ended up getting very popular on social media. It read: “Epilepsy is a collection of Rare Diseases”.

I believe this probably holds true for all medical fields, where as we gain insights into the cause (etiology) of diseases we realize that one large disease is actually many orphan-size diseases all sharing some common phenotype. But it is important to talk about this, and it was important to hear this message in the large session, because it captures where much of the attention right now is going within the epilepsy space: to the rare diseases.

And this was particularly visible at AES 2023, where many of the pharma stands at the exhibit floor and pharma-sponsored sessions focused on rare epilepsy syndromes. As last year, this was largely focused on the most famous syndromes: Dravet syndrome, LGS and TSC; and this year also included CDD, the 4th rare epilepsy syndrome with an approved treatment, and the subject of an additional Phase 3 trial by UCB pharma.

Yet the poster session gave us a glimpse into the future, and I would like to highlight a poster from Biogen on KCNT1 and two from UCB on STXBP1 and SLC6A1. Although all preclinical, these posters are important because they illustrate how the large companies are now proactively working on the genetic epilepsy syndromes, not just watching the field (as they did at first) or buying the orphan drugs developed by others (more recently). This is an important step for the industry.

With large biotech and pharma now on board with genetic epilepsy syndromes, we are reaching a more mature stage in that transition from only working on seizures to also working on genetic causes. And this is happening without taking attention away from the larger seizure treatment space, where I would highlight the impressive results with XEN1101 so far in focal-onset seizures and potential also for generalized seizures. This is a very good scientific time for the epilepsy drug treatment space in general.

2 – RARE EPILEPSIES AS A TRANSITION POINT IN THERAPY DEVELOPMENT IN EPILEPSY

Are rare epilepsy syndromes the future of epilepsy treatment? Not at all. The syndromes are rather a natural step in the transition from symptomatic treatments to treatments that treat the cause of the disease.

I really liked a presentation by Dr Gemma Carvill from Northwestern about the history of epilepsy. She highlighted how most of the progress so far has been not on efficacy (we always hit that 30-35% of refractory patients) but on having better tolerability, and how more recent development focused on rare epilepsy syndromes, then on genetic treatments for these syndromes, and how the future direction is to use those technologies to treat epilepsy at large. When applied to the non-monogenetic epilepsies, the main approaches would be gene regulation approaches, moving up or down the expression of important targets, instead of activating or inhibiting proteins as small molecules often do.

Important advances to modulate gene expression in epilepsy are dCas9 approaches (for example Colasante 2020), the use of activity-dependent promoters (for example Qiu 2022), or the targeting of non-coding RNAs (reviewed in Stine 2023). And one of the best examples of going beyond the rare epilepsies is the AMT-260 gene therapy program from uniQure for Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Gene therapy trials are not only for monogenetic epilepsy!

So genetic epilepsy syndromes are not the ultimate destination, but the first application of a new way of treating epilepsy, and this is becoming more clear as the epilepsy field evolves.

3 – PRESSURE IS HIGH, ALL SYNDROMES NEED BETTER TREATMENTS

Dravet syndrome is one of the epilepsy syndromes that has received the most attention from the industry. It has three drugs approved, soticlestat in phase 3 trials, and is the target of the most advanced clinical trial with a therapy designed to correct the cause of an epileptic syndrome: the ASO STK-001 from Stoke to correct the haploinsufficiency in SCN1A. This makes Dravet syndrome the “lucky syndrome”, and I have even seen grant proposals for Dravet turned down because it was considered “already done” by reviewers.

Yet at the Dravet syndrome roundtable we got to hear about 6-year old Anna and her journey with Dravet syndrome from her grandpa Ted Odlaug, who is the current president of the US Dravet Syndrome Foundation. During her short life, Anna has tried multitude of anti-epileptic drugs, including the three approved for Dravet syndrome, yet her epilepsy has gotten worse and worse and she currently has no days without seizures. She also has the cognitive development of a 2-year old, limited vocabulary, and her high seizure frequency including nocturnal seizures place her at very high risk for sudden death (SUDEP). Yet she got the “lucky syndrome”, the one with the most advances towards treating the symptoms and the cause.

This is something important to hear and to remember. All of what we have in epilepsy syndromes are some treatments approved to treat seizures, which work in SOME patients and that are tolerable by SOME patients. The treatments to correct the cause of these diseases are still in early development and still only accessible in the context of clinical trials. And this holds true even for the “lucky syndrome”. Most other syndromes are still behind in terms of therapy development.

So there is a big gap between the science, where we have cured the mice with SCN1A deficiency with several gene therapies and ASOs, and what patients in the real world like Anna have access to. Why is there such a progress gap between science and patient care? Part of it is time, treatments simply take years to get from the lab to the market, but we are also facing challenges bigger than time. And we are seeing these additional challenges as the first disease-targeting programs make their way to clinical trials and progress slows down. I discuss this in the next section. For this section my main message is that all syndromes need better treatments, and that none of them is yet “done”.

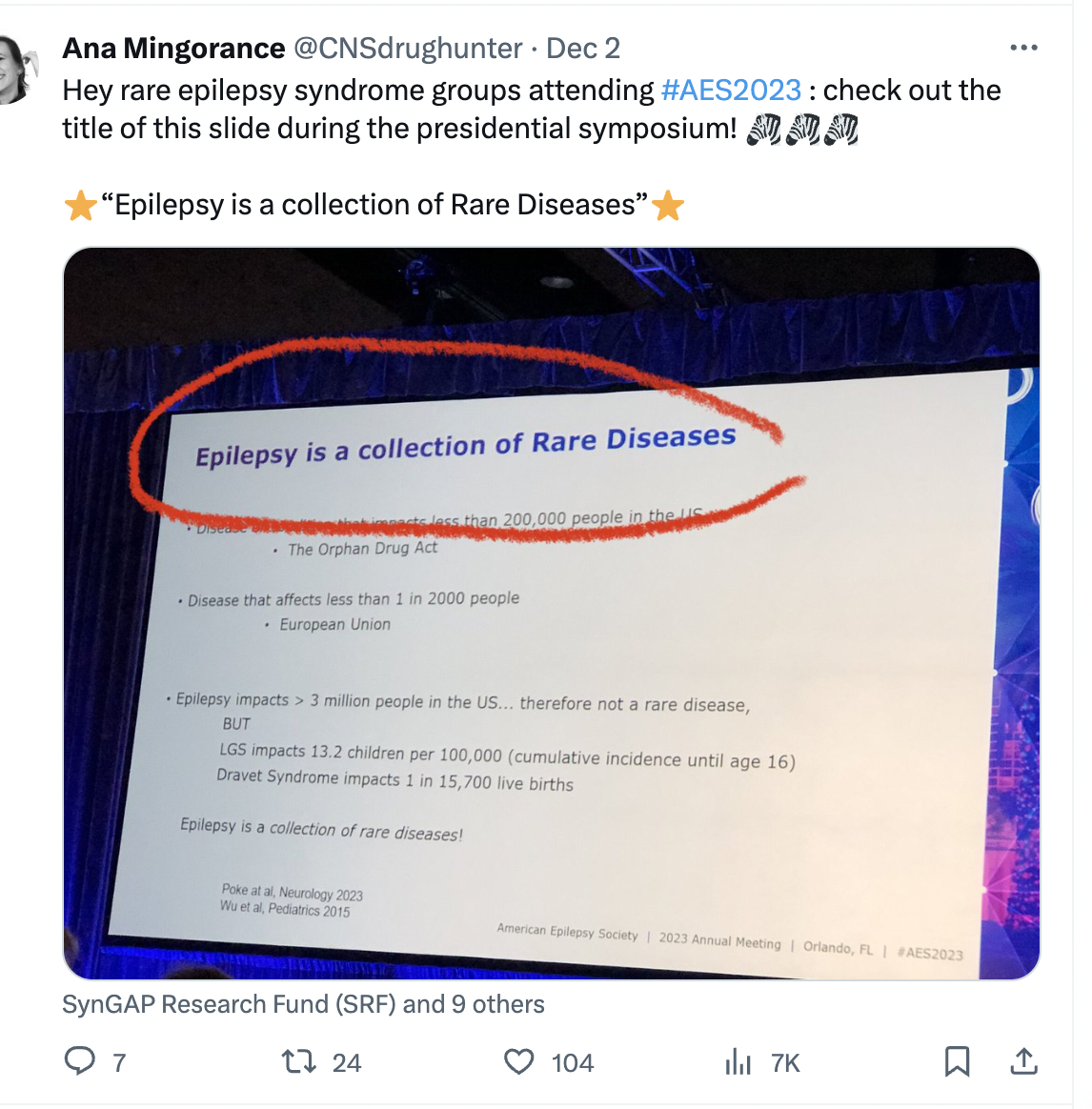

4 – RARE DISEASE THERAPY DEVELOPMENT HAS THREE MOUNTAINS TO CLIMB

Do you know the metaphor of a climber struggling to climb a mountain only to reach the summit and realize that there are other mountains just as high behind it? I believe this is where we are right now in developing disease-targeting treatments for genetic epilepsy syndromes, we are getting to the summit of that first mountain and looking at the next two. It turns out that getting gene-targeted treatment to trials was just the first mountain.

We had many discussions about these challenges during AES 2023. In fact, this was probably the most common topic across my many discussions with other attendees.

Mountain 1: Science.

Science has been advancing quite well. There are many preclinical programs with gene therapies and ASOs ongoing for a growing number of epilepsy syndromes, and we start having clinical trials. This year we have seen newer data from Stoke showing that with the highest dose of STK-001 they can have profound seizure reduction in patients with Dravet syndrome, and that even with moderate doses they can see improvements in non-seizure domains like communication. And Praxis has also started clinical trials with another ASO, PRAX-222, this one to reduce SCN2A in patients with gain-of-function mutations. This is in addition to Praxis’ small molecule trial for SCN2A and SCN8A gain-of-function DEEs.

We have also seen this year hopeful clinical trials results in Angelman syndrome (Ultragenyx) and Rett syndrome (Taysha) that make us all very hopeful that the neurodevelopmental field is getting closer to true disease-modifying treatments. So overall we start seeing the transition from preclinical ASO and gene therapies to clinical trials. This is just the first mountain.

Mountain 2: Regulatory.

This is a difficult one. We are still not sure how to design a clinical trial to show the difference between correcting the gene versus treating the seizures, and there are no precedents for a broader label to treat the disease (all we have are approvals “for the treatment of seizures in syndrome X”).

The patient community, clinicians and the companies developing treatments to target the cause of the epilepsy syndromes are working to solve this challenge by running observational clinical trials to validate non-seizure outcomes and endpoints.

The most advanced studies are the ones on Dravet syndrome by Stoke and Encoded, that have documented how, for example, the number of seizures in Dravet syndrome remains constant over time (up to 2 years!) as a group average. So while one patient might get better or worse, if you run a trial the number of seizures should balance out and remain stable. Many other symptoms are also stable or improve just a little, which will help us interpret open-label studies that may show improvements. And there are also other endpoint-enabling observational studies going on for CDD, SYNGAP and STXBP1 (at least) that I know.

We still don’t know which of these scales will be useful in clinical trials to show improvements beyond seizures, or how to convert the scales into specific endpoints, but in the meantime some of the companies with approved drugs to treat seizures in DEEs are leaning quite far into almost claiming efficacy in non-seizure outcomes by relying on caregiver surveys. And this is a development that worries me. We already have the problem in rare diseases of having to overrely on case studies due to so few placebo-controlled trials. And now we are adding the problem of companies with anti-seizure medications using caregiver surveys not reviewed by regulators to talk about improvements in behavior and cognition. This was particularly visible in 2023, and it almost creates two tracks with different burden of proof for non-seizure outcomes: one of post-approval caregiver surveys for small molecule anti-seizure drugs, and one of years of endpoint-enabling studies followed by year-long trials with not-yet-validated outcome measures for ASO and gene therapies. I’m not liking this development.

Mountain 3: Market.

A common challenge for rare diseases is not having enough patient numbers for an attractive return-on-investment. We have seen this addressed in rare epilepsy syndromes by developing the same molecule for a group of rare diseases. For example Epidiolex approved for Dravet, LGS and TSC; Fintepla approved for Dravet, LGS and in Phase 3 trials for CDD; and soticlestat in Phase 3 trials for Dravet and LGS. But running multiple parallel trials is expensive, so companies focus only on the largest syndromes.

A near-future regulatory innovation might be clustering syndromes into a broader label for drug development. This year we heard from the company Longobard, with a Phase 2 basket trials in DEEs, that they will consider discussing with regulators the potential to keep the combined DEE target population for Phase 3 trials and approval. I see regulatory challenges to do this but I also see it as the only way to get clinical trial data for many of the DEEs beyond the top 6 or so in terms of patient numbers, so I would love to see this happen.

The company Tevard is also considering a combination of DEEs, in their case because they are developing a gene therapy to help the cell skip premature stop codons caused by non-sense mutations, so their case is very similar to basket trials in the cancer field. In the case of Tevard, the target population would be genetic DEEs caused by non-sense mutations, and the common primary endpoint could be reduction in seizure frequency so one trial could test them all. Even a clinician working for Jazz told me that they had been asked by many clinicians to run studies with Epidiolex in groups of biologically-related DEEs (for example ion channels, or synaptopathies) so this definitely seems to be a conversation that we are hearing loudly in 2023 and that will likely turn into action.

5 – IMPRESSIVE PATIENT GROUPS

I have been working on rare epilepsies and supporting patient groups for 12 years now. And oh boy has that changed. Patient advocacy in 2023 is much more advanced and professional than how it was back in 2011.

The four epilepsy syndromes that have drugs approved all have very impressive patient-run foundations and patient groups behind them. See for example how the AES 2023 Extraordinary Contribution Award went to Mary Anne Meskis, Executive Director of the Dravet Syndrome Foundation. But they are no exception anymore. During AES 2023 I had a chance to interact with some of the patient groups for syndromes that still have no treatment approved (or advanced clinical trials) that were equally impressive.

Some of these deserve a shout out:

I attended the SYNGAP conference by the SynGAP Research Fund the day before AES. I wrote a separate summary about this conference, but this group is amazing in how they are tackling the key challenges to therapy development in their field, scientific/medical/industry community building, and patient mobilization including a very international footprint.

I caught the end of a meeting between the FamilieSCN2A Foundation and a biotech company, since I was next to meet with the company, and I was very impressed with their print slide-deck summarizing all of the resources and learnings from the SCN2A field. This included the entire list of mouse models and efforts to also validate outcome measures, for example in communication. This will help companies get up to speed with SCN2A quickly, and I’m pretty sure it will help start treatment programs by making it easier to choose this syndrome.

It is a tradition for me to sit down with Charlene and John from the STXBP1 Foundation every year at AES and compare notes about their field and the syndromes that I am working on. This year Charlene showed me one slide with the STXBP1 pipeline in 2019, having only one program for potential repurposing with nothing else on the horizon. And then the 2023 pipeline slide, with 11 programs in development including several gene therapies being developed by companies. Talk about progress!

CONCLUSSION: HAVE WE REACHED ESCAPE VELOCITY?

In science: yes. We are seeing a growing number of ASOs and gene therapies being developed for several of the neurodevelopmental syndromes with epilepsy. Transition to clinical trials is still a bit slow but the progress across many diseases is notable.

In regulatory path and market conditions: no. We are still not sure how to design a clinical trial to show the difference between correcting the gene versus treating the seizures, there are no precedents for a label that goes beyond seizures, and the market is still a limitation, leading to companies always choosing the largest syndromes and neglecting the other hundred or more.

We are seeing some development to address these challenges. Some are good developments, like considering how to get several syndromes into a single clinical program and approval. Some are (as I see them) bad developments, like companies promoting cognitive and behavioral efficacy for their drugs using a language identical to the one they use for seizure efficacy, which is the only one approved and on label.

Another development is the arrival of gene therapies to non-genetic epilepsy trials, which is very promising. Also exciting is to see big bio and big pharma proactively working on the genetic epilepsy syndromes, not just watching the field or buying the orphan drugs developed by others. And we are also now getting the results of the observational studies that are being carried out for several DEEs to identify endpoints for more complex clinical trials. So overall this was a good year.

For 2024 my hope is to:

see some answers to the regulatory challenges, with learnings from Stoke and also from other companies in the neurodevelopmental (non-epilepsy) field.

see more clinical trials started with treatments targeting the cause of the disease (potentially from the group of SLC6A1, SCN2A Loss-of-function, and CDD?)

see more mouse proof-of-concept data with treatments targeting the cause of the disease. We have many ideas and in vitro data, but not enough clinical candidates yet.

And I hope to see that in Los Angeles, for AES 2024.

Ana Mingorance, PhD

Disclaimer: These are my own impressions from the presentations and topics that I was most interested in. I write these texts with the parents of individuals with rare epilepsies in mind, so excuse also my lack of technical accuracy in parts.

REPASO DEL FORO CDKL5 2023

La novena edición del Foro CDKL5 tuvo lugar en Boston, los días 6 y 7 de noviembre. El Foro es una reunión anual que organiza la Fundación Loulou y en la que científicos y miembros de la industria farmacéutica se reúnen con representantes de la comunidad de pacientes para repasar los últimos avances en el campo.

Este es un repaso para los grupos de pacientes de las principales novedades del Foro CDKL5 2023.

FORO 2023

Hace ya nueve años que la Fundación Loulou organiza una reunión anual, el Foro CDKL5, donde los científicos de academia y de industria trabajando en el síndrome de deficiencia en CDKL5 (CDD), junto con representantes de los grupos de pacientes, se reúnen para compartir las últimas novedades y avanzar hacia tratamientos y una cura. Tenéis el resumen del año pasado aquí.

La edición de 2023 tuvo lugar en Londres los días 6 y 7 de noviembre, y volverá a Boston en 2024. Cada año digo que este ha sido el mejor Foro, pero es que es verdad. Tengo 47 páginas de notas por toda la información nueva y todos los momentos importantes que nos dio el Foro. Así que voy a intentar resumir las conclusiones principales de la edición de este año, no incluyendo todas las presentaciones sino centrándome en los temas principales y los progresos que vimos, que son muchos.

1. SEGUIMOS DESCUBRIENDO COSAS SOBRE CDD

El Foro siempre arranca y cierra con la voz de la comunidad de pacientes. Este año fue Cristina, de la Asociación de Afectados CDKL5, quién abrió el Foro con un mensaje muy poderoso. Nos explicó que cuando les llegó el diagnóstico de su hija, aprendieron que “viviría una vida a medio camino entre incierta y horrible”. Y que por eso, para allá, la investigación es la esperanza.

Y cada año la investigación nos sigue enseñando cosas nuevas sobre CDD que tienen importantes aplicaciones de cada a entender la enfermedad o a posibles tratamientos. Aquí os cuento algunas, y mirad también la sección 6 de este resumen.

La Dra Lauren Orefice de Boston nos enseñó como el rechazo a ciertas texturas en CDD es consecuencia de cambios sensoriales, no de comportamiento. Los ratones con CDD tienen las neuronas sensoriales demasiado sensibles a las texturas rugosas, reaccionan demasiado fuerte, y por eso suelen rechazar esas texturas. Y es muy posible que lo mismo pase en las personas con CDD que insisten en comer texturas específicas.

Varios proyectos de varios laboratorios coinciden en ver cambios de conectividad funcional en CDD, pero no cambios estructurales. O sea que las neuronas están en el sitio correcto y en general el cerebro está bien y bien conectado, pero algunas neuronas disparan juntas más de lo que deberían, y otras no disparan juntas tanto como deberían (eso es la conectividad funcional). Y para mi esto es muy prometedor de cara a tratamientos porque cuando normalizamos la actividad neuronal podemos obtener cambios en este tipo de conectividad funcional. Lo que sería mucho más difícil de arreglar es cambiar una neurona de sitio.

Sir Adrian Bird nos dio una de las ponencias estrella. Se hizo famoso porque fue el primer científico que demostró que el síndrome de Rett es reversible en ratones, y n os explicaba que en Rett (gen MECP2) tener poco o tener mucho es problemático, con lo que todas las terapias génicas en desarrollo para Rett (que es por falta de MECP2) llevan mecanismos de freno para no llegar a causar sobreexpresión (demasiado MECP2). Pues una de las sorpresas de este año nos vino de la Dra Sharyl Fyffe-Maricich de Ultragenyx, que nos demostró algo que sospechábamos desde hace algunos años: el cuerpo ya pone freno a cuanto CDKL5 puedes producir y no te deja hacer sobreexpresión. Nos enseñó datos con ratones y con primates, donde da igual cuanta terapia génica les des, las neuronas se comen el exceso de CDKL5. Y eso es buena noticia porque las terapias génicas de CDKL5 serán más fáciles al no tener que incorporarles ningún mecanismo artificial de freno.

Rechazando texturas y aprendiendo de Rett

2. ELIMINANDO BARRERAS PARA AVANZAR EL DIAGNÓSTICO Y LA INVESTIGACIÓN

El Foro 2023 nos trajo muchos ejemplos de generación de modelos de forma colaborativa, y quiero destacar un progreso en torno a diagnóstico y uno sobre modelos de epilepsia.

Un diagnostico genético no siempre es fácil de interpretar. Por ejemplo, si vuestro hijo o hija tiene una mutación en el gen CDKL5 que le rompe el gen, es fácil de interpretar en un test genético. Pero si tiene las de una letra cambiada por otra… esas son difíciles de interpretar y acabamos con un VUS (de las siglas en inglés para “variante de significado incierto”) y con un diagnóstico sin confirmar. Un equipo de la Telethon en Italia está haciendo en el laboratorio todas las mutaciones de cambio de letra posibles en CDKL5, probándolas en células, y van a poner todos los resultados en una base de datos. De ese modo, cualquier laboratorio genético encontrará respuesta para cualquier cambio de letra que vean en un niño. No más VUS en CDKL5. Un proyecto super chulo.

Y otro progreso enrome en generación de modelos de investigación que vimos este año es que por fin tenemos buenos modelos de epilepsia! La Dra Liz Buttermore nos enseñó un modelo in vitro, a partir de neuronas de pacientes en placas de cultivo, donde las neuronas de pacientes tienen una hiperactividad clara (disparan mucho). Y como científica que trabajó en la industria farmacéutica os puedo decir que este es el tipo de modelo que me hubiera gustado tener para probar fármacos. Luego está si recordáis el Dr Muotri de California que hace organoides (bolitas de neuronas) a partir de células de pacientes, que son como bolitas de corteza cerebral. Pues este año la Dra Rebeca Blanch, de su laboratorio, nos enseñó como las van a hacer tálamo-corticales para que puedan tener ese circuito tan importante para la epilepsia. Y el Profesor Peter Kind nos enseñó cómo su laboratorio ha encontrado el foco epiléptico en el cerebro de ratas con CDD, y ahora pueden estimularlo directamente para provocarles crisis cada vez que quieren. Este es un modelo fantástico para estudiar tratamientos. Sin duda en este año hemos tenido un avance tremendo en esta área.

Deshaciendo VUS y epilepsia en ratas con CDD

3. LOS “4 APROBADOS” Y LOS FÁRMACOS EN DESARROLLO

En 2022 se aprobó ganaxolona en Estados Unidos y se convirtió en el primer fármaco aprobado para CDD. Luego en 2023 nos ha llegado la aprobación Europea.

Y para que veáis lo excepcional y lo difícil que es tener un fármaco aprobado para un síndrome con epilepsia, os voy a repetir lo que dije durante mi charla en la sesión sorbe tratamientos: hay más de 300 síndromes con epilepsia, y solo 4 tienen un tratamiento aprobado. Estamos hablando de Lennox-Gastaut, esclerosis tuberosa, síndrome de Dravet y CDD. Ya está, solo esos 4.

Y una empresa de biotecnología empezó a llamarlos este año “los 4 aprobados”, por ser la excepción. Y para las empresas de desarrollo de tratamientos, estos 4 aprobados son más fáciles que cualquier otro, porque ya existe un precedente y por tanto respuestas a muchas preguntas de cómo llegar a la meta en esa enfermedad, y eso los hace más atractivos para tener más tratamientos. Por eso el valor de ganaxolona va más allá que el valor como medicamento.

Hemos pasado de haber tenido cero ensayos clínicos, a tener 8 en 8 años, y formar parte de “los 4 aprobados”. Para ser una enfermedad relativamente nueva, hemos empezado muy fuerte.

Y ahora la pregunta que nos queda es “y después de ganaxolona qué”. Y en el Foro vimos varias presentaciones de las terapias que vienen después, y que resume en esta sección y las tres siguientes.

Marinus anunciaba en el Foro que acaban de firmar un Programa de Acceso Global para llevar ganaxolona a los países donde no está disponible comercialmente (o en proceso de estar disponible como sería el caso de Europa). Su web tiene un correo de contacto para que los médicos puedan informarse. También nos enseñaron datos de que ganaxolona mantiene eficacia durante al menos 2 años.

UCB Pharma estuvo representada por dos personas, incluida la directora médica que dirige todos los ensayos clínicos, y nos explicaban que el ensayo clínico de fenfluramina para CDD en fase 3 está en marcha en Asia, Europa y Estados Unidos, con una web muy fácil de recordar: cddstudy.com

También repasamos varios fármacos en desarrollo para otras epilepsias o para otras enfermedades de neurodesarrollo, y que podrían potencialmente incorporarse a la lista de ensayos para CDD. Esos incluyen otros fármacos que actúan sobre el GABA, los activadores de KCC2, los inhibidores de Cav2.3 (os cuento más en la sección 6) y algunos tratamientos dirigidos a la flora intestinal que me resultan muy interesantes.

La conclusión de esta sesión es que ganaxolona fue solo el principio y que hay muchas opciones por detrás.

Presentaciones de empresas con terapias en desarrollo

4. CLINICAL TRIAL READINESS: CÓMO LA COMUNIDAD DE PACIENTES ESTÁ HACIENDO POSIBLES LAS TERAPIAS DEL FUTURO

Al terminal el Foro nos han llegado correos de gene de empresas que vinieron a Londres y todos destacan esta sesión como muy importante. Como nos escribió uno literalmente “esto va a atraer la participación de más empresas”.

Se trata de la sesión sobre biomarcadores y escalas clínicas, que responden la pregunta de “cómo vamos a medir en ensayos todo lo que no es epilepsia”. Y es particularmente crítico para los ensayos con terapias génicas, y en los últimos 12 meses hemos tenido muchos avances importantes.

Los biomarcadores son formas de medir cambios en el cerebro sin tener que hacer una biopsia (por razones obvias algo no viable para el cerebro). Un tipo de biomarcadores son los que podemos medir en sangre (los niveles de azúcar serían un biomarcador de diabetes) y el Dr Massi Bianchi de Ulysses nos enseñó datos muy prometedores de poder medir plasticidad neuronal en un análisis de sangre, si nos fijamos en dos marcadores en concreto. Otro tipo de biomarcador son los de técnicas de imagen cerebral, y el Dr Eric Marsh de Filadelfia nos enseñaba también datos de cómo hay algunas señales del electroencefalograma que correlacionan con la severidad de la enfermedad en CDD. Son dos tipos de marcadores que muy posiblemente se usarán en ensayos clínicos.

Luego el Dr Marsh nos compartió los resultados interinos de un estudio americano para desarrollar nuevas escalas clínicas para CDD. Ya han completado la primera parte y ahora las están refinando y confirmando, y tiene muy buena pinta. Y quiero destacar un detalle: este es un estudio observacional con más de 100 participantes, y 100 es justamente el número de pacientes de un ensayo de Fase 3 en CDD, así enhorabuena a la comunidad de pacientes por movilizarse de tal manera para hacer este estudio y los de los biomarcadores sean posibles.

Y por último el Dr Xavier Liogier, de la Loulou Foundation nos actualizó sobre el estudio CANDID, que es parte de un consorcio con varias empresas que están desarrollando tratamientos para CDD: El estudio CANDID busca validar en CDD escalas que ya se han usado en ensayos para otras enfermedades. Hace un año, Xavier nos contaba que el primer paciente ya había entrado al estudio. Ahora 12 meses después nos decía que ya tienen más de 100 visitas programadas con lo que cierran reclutamiento, y nos enseñó ya muchos de los datos que tienen viendo cómo estas escalas se aplican a CDD. El gráfico de reclutamiento al final parecía exponencial, y de nuevo muestra la tremenda movilización de la comunidad de pacientes para hacer este estudio posible.

El Dr Billy Dunn, que era el director de neurología de la FDA y ahora es Asesor Senior de la Fundación Loulou, fue moderador de esta sesión y alabó el espíritu de colaboración de los participantes por enseñarnos datos mientras los estudios están aún en curso, y destacó también el valor de estar construyendo “un menú del que elegir” para hacer posible diseñar ensayos complejos en CDD.

Proyecto de biomarcadores de Ulysses y curva de reclutamiento exponencial de CANDID

5. HACER UNA TERAPIA GÉNICA ES COMO CONSTRUIR UNA CASA

Hace un año, en el Foro 2022, pensábamos que en este Foro tendríamos la noticia de que una de las terapias génica había obtenido permiso para empezar ensayos. Pero todavía no hemos llegado a esa noticia.

Y hablando con algunos de los padres en el Foro sobre cómo explicar a gente que no es científica las implicaciones de que haya retrasos en este tipo de proyecto complejo, lo mejor que encontramos es el ejemplo construir una casa que compras sobre el plano. Si no lo habéis vivido directamente seguro que conocéis a alguien a quien le ha pasado: firmas sobre plano, el constructor te dice el plazo en el que te podrán dar las llaves, y al final raramente es en esa fecha. Y es que hay demasiadas etapas que pueden añadir retrasos, pero eso no quiere decir que un retraso indique que hay un problema con la casa o que no te la llegarán a entregar. Puede que hacer los cimientos se retrase por un invierno largo, el aislamiento haya que retocarlo, la estructura exterior de la casa nos de alguna sorpresa… añade a eso todas las instalaciones, los acabados exteriores y los interiores… hay demasiados pasos que pueden alterar esas predicciones de fechas.

Hacer una terapia génica es como construir una casa. Los expertos en biotecnología saben cómo hacer estas terapias, ya lo han hecho antes, pero aún así tienen que hacer la tuya desde el principio y hay muchos pasos complejos incluidas las inspecciones (igual que en una casa!) que acaban moviendo los plazos pero que son parte normal de hacer una terapia génica.

Lo que sabemos hoy es que tanto la terapia génica de Ultragenyx como la que está haciendo la Fundación Loulou con la Universidad de Pensilvania ya han hablado con las agencias reguladoras en 2023, y que ambas esperan obtener la aprobación para ensayos en 2024. Así que el proceso ha sido bueno, aunque no tan rápido como queríamos. Y Sharyl de Ultragenyx fue muy clara en este Foro: no se han encontrado ninguna señal adversa de seguridad con la terapia génica de CDD en ninguno de sus estudios con animales realizados hasta la fecha, incluyendo los estudios de seguridad en primates. Es simplemente un caso de tener que hace run poso más de trabajo para pasar la inspección de la casa.

En resumen al final del año pasado nos dijeron “creo que te daremos las llaves de la casa el año que viene” y no ha sido así, pero no hay ningún problema con la casa. Es que es de verdad muy complicado atinar con las predicciones en proyectos tan complejos.

Y en el Foro 2023 repasamos también los progresos en desarrollar terapias génicas con modalidades nuevas, de las que no hay aún precedentes aprobados para otras enfermedades. En concreto vimos un update del Dr Kyle Fink, que está desarrollando una terapia génica basada en CRISPR para abrir la segunda copia del gen CDKL5 en niñas (la del segundo cromosoma X), y de Kelcee Everette que trabaja en el laboratorio del Dr David Liu y que también está desarrollando una terapia génica basada en CRISPR, en este caso para arreglar la letra mutada o poner la letra que falte en el gen. En ambos casos se centran en aumentar la eficacia de corrección del gen, aumentar la selectividad (que no cambie genes que no tocan) y hacer los CRISPR más pequeños porque todavía no caben en los virus que se usan para terapia génica. Estos proyectos son como hacer casas con materiales nuevos, que no se han usado todavía nunca, y que de momento son demasiado grandes para la casa. Con lo que los plazos para su llegada a ensayos son impredecibles, pero el progreso es muy tangible. Y a mi me parece aún increíble que CDD sea de las primeras enfermedades a las que se están aplicando estas terapias génicas del futuro.

Varias terapias génicas en desarrollo

6. DOS SORPRESAS QUE HAN ABIERTO DOS PUERTAS

No todo está tardando más de lo que pensábamos. Hay cosas que están pasado más rápido de lo que podríamos imaginar, y vimos dos ejemplos notables de esto en el Foro.

Aprendiendo de la evolución

El Dr Ibo Galindo del Príncipe Felipe nos presentó un análisis evolutivo fascinante del gen CDKL5 desde la primera célula de la evolución y pasando por el árbol entero de la vida. Resulta que las plantas tuvieron en origen un gen CDKL, pero lo perdieron (¡tienen deficiencia en CDKL5!), que el gen CDKL5 original fue el 5, pero que luego se duplicó varias veces dando lugar a las 5 versiones. Y también aprendimos que mientras que las cinco formas CDKL1-5 tienen funciones importantes de regulación del esqueleto celular (el citoesqueleto), el gen CDKL5 parece haber adquirido funciones nuevas en vertebrados. Había dos conclusiones importantes: (1) es posible que haya redundancia funcional entre alguno de estos genes, y (2) CDKL5 tiene una cola especial en vertebrados que indica que tiene una función que no es de regular citoesqueleto.

Y estas conclusiones nos pusieron un marco de fondo perfecto, para dos proyectos que vienen del laboratorio de la Dra Sila Ultanir del Crick Institute y que os cuento más abajo. El laboratio de Sila se llevó el premio al Laboratorio del Año en el Foro 2023, pero a mi me gusta llamarlo el laboratorio de la década por el impacto que tienen en la investigación en CDD.

1. Redundancia funcional. Encontramos el parálogo. Encontramos avenida terapéutica.

En biología, un gen paralógo es el que nace por duplicación de otro, y ahora se parecen tanto que posiblemente compartan algunas funciones. Esto es lo que pasó en la atrofia muscular espinal, esa enfermedad neuromuscular letal en bebés que los científicos solucionaron porque encontraron un gen SMN2 (¡un parálogo!) que podía compensar por la falta de SMN1.

El laboratorio de Sila se dio cuenta de que una de las proteínas de citoesqueleto más famosas controladas por CDKL5, que se llama EB2, no estaba controlada solo por CDKL5 en neuronas, había otra kinasa que también la regulaba. ¡Y buscando quien era encontraron que era CDKL2! Y ahora están buscando la posibilidad de aumentar la expresión de CDKL2 en CDD para compensar por la falta de CDKL5. Y hay una posibilidad de hacerlo con ASOs. Una de las ponencias invitadas fue por el Dr Stanley Crooke, que es el fundador de la empresa Ionis (la que hizo el primer oligonucleótido antisentido o ASO para tratar la atrofia muscular espinal), y que luego a fundado una ONG llamada N-Lorem para hacer ASOs específicamente para gente que tiene enfermedades genéticas “nano-raras”. Y dijo en su charla que “CDKL2 tiene los elementos arquitecturales genéticos necesarios para hacerle un buen candidate a aumentar su expresión usando ASOs”. Y se eso sabe mucho este hombre.

Ha sido muy inesperado enterarnos de que quizás podamos seguir los pasos de la atrofia muscular espinal al encontrar un segundo gen que pueda compensar con el primero (al menos en neuronas, porque parece que en otros órganos son otros CDKL los que compensan). Ha sido un descubrimiento y comienzo de un proyecto terapéutico que nos ha llegado super-rápido.

2. Predicción que tiene dianas que no son de citoesqueleto. Encontramos la diana. Encontramos avenida terapéutica.

La Dra Marisol Sampedro, que trabaja con Sila, nos presentó el año pasado su descubrimiento de que CDD podría ser parcialmente una canalopatía porque encontró que el canal de calcio Cav2.3 era una diana clave de CDKL5. Cuando falta CDKL5, el canal Cav2.3 no está fosforilado (el interruptor que le pone CDKL) y se queda demasiado abierto, y la neurona se queda demasiado activa. Así que lo que necesitaríamos son inhibidores de este canal, y esto lo repasamos en el resumen del año pasado donde lo llamé un descubrimiento muy importante.

Pues un año después teníamos en el Foro una empresa nueva llamada Lario Therapeutics contándonos que están desarrollando fármacos inhibidores de Cav2.3 para CDD y para otro síndrome causado por mutaciones de ganancia de función en ese gen (también tienen Cav2.3 con demasiada actividad). El director científico de Lario nos explicó que están terminando la optimización química de los compuestos y que pasarán a los estudios de seguridad en animales previos a ensayos clínicos. Estamos hablando de una medicina de precisión para CDD y esto de verdad que nos ha llegado mucho más rápido de lo que podríamos haber imaginado.

RESUMEN: MOMENTUM

Este año aprendimos que la primera terapia génica está tardando más de lo que pensábamos, pero muchas otras cosas están pasando más rápido que lo que hubiéramos pensado, como esas dos nuevas oportunidades terapéuticas (CDKL2 y Cav2.3) que eran inimaginables hace tan solo dos años. También vimos por fin los frutos de varios esfuerzos de varios años de duración, como los dos estudios observacionales que han reclutado más pacientes que un ensayo de Fase 3, o tener por fin modelos de epilepsia in vitro y en ratas que permiten el tipo de experimento que necesitan las empresas farmacéuticas. Así que la impresión que yo me llevo es de que la velocidad de progreso se está acelerando, un poco como este gráfico de reclutamiento del estudio CANDID, y que hemos llegado a un momentum importante.

Y esa es justamente la palabra que Stan Crooke usó cuando se subió al podio y nos dijo “el momentum que tenéis ahora mismo en investigación en CDD es palpable”. Por eso creo que es buena palabra para capturar lo que vimos este año (aunque no la usemos mucho en español, es una especie de inercia inparable).

Y ese momentum se apoya sobre dos pilares que también se mencionaron mucho durante este Foro: la determinación y el espíritu de colaboración.

La voz de las familias en el Foro 2023

Así que os dejo con las frases de tres de los padres/madres que hablaron en el Foro 2023 y que capturan estos mensajes:

Cristina, de la Asociación de Afectados CDKL5, que nos recordó que “las personas con CDD son increíbles y se merecen lo mejor”

Majid, de la Fundación Loulou, que reconocía el camino que queda por recorrer explicando que “hemos avanzado más rápido y más lejos de que lo hubiera imaginado, gracias a todos vosotros. Pero al mismo tiempo, nunca es tan rápido ni tan lejos como querríamos las familias” y pedía a la audiencia que se volvieran a comprometer a curar la enfermedad con aún más pasión, más motivación y más determinación

Y por último Heike, en representación de la Alianza Internacional, nos hablaba de la personalidad de su hija, de los esfuerzos que los diferentes miembros de la Alianza están llevando a cabo, y cómo “estamos en esto juntos”.

Ya se que digo lo mismo todos los años, pero el de este año fue el mejor Foro que hemos tenido.

Espero que os haya gustado el resumen. Ya me diréis lo que os parece en los comentarios.

Ana Mingorance, PhD

Nota: este texto captura mis impresiones de las presentaciones del Foro que más me interesaron, no es un texto oficial del congreso emitido por la Fundación Loulou. Escribo estos resúmenes para los padres de personas con CDD, así que a veces me tomo ciertas licencias a la hora de explicar las partes mas técnicas.

MAIN LESSONS FROM THE 2023 CDKL5 FORUM

For the past nine years the Loulou Foundation hosts an annual meeting where scientists and drug developers working on CDKL5 deficiency, together with representatives from patient organizations, meet to discuss the latest advances.

Here are the main news and take-home messages from the 2023 CDKL5 Forum that took place in November 6-7 2023

2023 CDKL5 Forum

For the past nine years, the Loulou Foundation has hosted an annual meeting, the CDKL5 Forum, where scientists and drug developers working on CDKL5 Deficiency Disorder (CDD), together with representatives from patient organizations, meet to discuss the latest developments in the field and to advance towards treatments and cures. You can find summaries from the past few meetings here: 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022.

The 2023 CDKL5 Forum edition took place November 6-7 in London, UK, and will return to Boston next year for the 2024 edition. Each year I say that this was the best Forum so far, but it is true. I wrote 47 pages with notes. There was so much good information and so many important moments! I will try to summarize the main take-home messages from this year’s Forum including the scientific pre-forum meeting. This won’t cover all the presentations, but rather focus on the main themes that we saw and the main progresses – which are many.

1. USEFUL NEW INSIGHTS INTO CDD

The Forum always opens and closes with the words from the patient community. This year, Cristina, from CDKL5 Spain, opened the conference with some powerful words. She explained that when they received their daughter’s diagnosis, they also learnt that their daughter “would live a life somewhere between uncertain and horrible”.

That’s why for her, research means hope.

And every year we keep learning new things about CDD that have important implications to understanding the disease and thinking about treatments. Here are 3 of those, and check out also point #6 in this summary.

Dr Lauren Orefice from MGH and Harvard showed us that food texture aversion in CDD happens because of sensory changes, rather than behavioral reasons. Mice with CDD have sensory neurons that are hyper-reactive to rough texture, so no wonder they don’t like it. This is probably the same for people with CDD who might have difficulties with specific food textures.

Several research projects keep finding functional changes in brains with CDD, rather than structural changes (Dr Tanaka, Dr Higley, Dr Fagiolini and others). This means that neurons are in the right place, and overall the brain is all well shaped and connected, but some neurons are firing together more than they should while others are not firing together as much as they should. To me, this is promising for treatments because normalizing neuronal activity can lead to plastic changes in this type of neuronal functional connectivity. What would be much harder is to try to correct having neurons in the wrong place.

We had a wonderful lecture by Sir Adrian Bird, who became famous after showing that Rett syndrome could be reversible in mice. He explained to us how in Rett syndrome too little or too much MECP2 are both bad options, so the gene therapies in development for Rett syndrome (too little MECP2) all incorporate control mechanisms to prevent running into overexpression MECP2. A big surprise from this Forum was Dr Sharyl Fyffe-Maricich from Ultragenyx confirming with data in mice and primates what we had suspected for several years: the body puts a limit to how much you can express CDKL5 and it will not let you get into overexpression (too much) of CDKL5. The neurons eat all of the excess away, no matter how much gene therapy you give them. This is very encouraging, because it makes gene therapies for CDKL5 easier since we don’t need to add that “break”.

Food texture aversion and learning from the Rett syndrome field

2. SOLVING KEY PROBLEMS TO ADVANCE DIAGNOSIS AND RESEARCH

The 2023 Forum showed even more collaborative reagent and model generation than previous years, and in particular I would like to highlight advances around diagnosis and seizure models.

Genetic testing is not always easy to interpret. For example, if your child has a mutation in the CDKL5 gene that breaks the gene, then it is easy to interpret in a genetic test. But what happens when the mutation changes a letter by another one? This one is hard, and we end up with VUS (variant of unknown significance) and an uncertain diagnosis. A team from the Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine (TIGEM) is making in the lab all of the possible letter changes in the CDKL5 kinase domain and will check all of their functions in cells and then put the results in a database. That way, genetic labs will always have an answer for any letter change that they find. No more VUS for CDKL5, what a cool project.

And another big research tool progress from this year was that lots of seizure-relevant models are finally available! We had Dr Liz Buttermore show us a beautiful plate assay with cells from patients with a very nice hyperexcitability signal in patient-derived neurons. As a former pharma scientist, I know this is the type of assay that I would like to use. If you remember from other years, Dr Muotri from UCSD had a great in vitro CDD model using organoids from brain cortex. This year Dr Rebeca Blanch from his lab showed us that they are now making thalamo-cortical organoids, to try to better recreate one the main epilepsy circuits. Very cool! And Prof Peter Kind showed us how his lab has identified an epilepsy hotspot in CDD rat brains and they are able to stimulate it to induce seizures whenever we want. That’s such as great epilepsy model! This year we had incredible progress in this area.

VUS databases and CDD rat seizure model

3. “THE APPROVED 4”, AND TREATMENT PIPELINE TODAY

CDD had the first drug approved in the US (2022) and Europe (2023).

To show you just how special and how hard it is to have a drug approved for a rare epilepsy syndrome, I will repeat here what I said in my talk during the treatment pipeline session: there are more than 300 epileptic syndromes, and there are only 4 epilepsy syndromes that have any drug approved. These are Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC), Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome (LGS), Dravet syndrome, and CDD. That’s it, just 4.

A pharma company recently started referring to these as “the approved 4” because it is so exceptional for an epilepsy syndrome to have a drug that has made it all the way to the finish line. For companies looking to develop treatments, these approved 4 are going to be easier and therefore more attractive than the others, because there is already a precedent and therefore many answers to how to get a drug to approval for them. So the value of ganaxolone goes beyond the value of the medicine.

We have gone from zero to 8 clinical trials in 8 years and have become part of the approved 4. This is a very strong beginning.

Now the question that remains is “what’s next”. At the Forum we had several presentations for the therapies that come next and many of the efforts to support them, which I summarize here and in the next three sections.

Marinus Therapeutics announced at the Forum that they have now signed a Global Access Program to help get ganaxolone to people with CDD in countries where it is not commercially available (or in process of becoming available, like is the case for Europe). Their website has a contact email for doctors to reach out to learn more about access. They also showed nice data of sustained seizure efficacy with ganaxolone over 2 full years.

UCB Pharma was represented by two speakers, including their CMO, who explained that UCB spends 30% of their revenue in R&D – this is a lot for the industry. And as you know some of that went to acquire Zogenix and their drug fenfluramine, which is now in Phase 3 trials for CDD. The trial has a website with an easy to remember name: cddstudy.com and you can see there all the countries where the trial is available in Asia, Europe and North America.

We also reviewed several drugs in development for other epilepsies or other neurodevelopmental disorders and that could potentially join the CDD pipeline in the coming years. These included other GABA drugs, KCC2 activators, Cav2.3 inhibitors (which we review in section 6) and some treatments that target the gut microbiome and that I find very interesting.

The conclusion for the session on the current CDD pipeline was that ganaxolone is just the beginning and that are multiple options coming behind it.

CDD therapeutic pipeline presentations

4. CLINICAL TRIAL READINESS: HOW THE PATIENT COMMUNITY IS MAKING THE FUTURE THERAPIES POSSIBLE

After the Forum we got emails from pharma and biotech industry professionals that attended the Forum and they all mentioned this session as very impactful. As one literally wrote, “this will attract more industry participation”.

This session was about biomarkers and outcome measures, which is “what to measure in trials that will look at more than seizures”. This is particularly critical for the future gene therapy trials, and the last 12 months have seen tremendous progress.

Biomarkers are way to see changes in the brain without directly taking a biopsy. One type of biomarkers are the ones we can measure in blood (glucose levels are a biomarker for diabetes), and Dr Massi Bianchi from Ulysses showed us very promising early data for measuring neuronal plasticity in a blood test by looking at two key markers. Another type of biomarker is using brain imaging, and Dr Eric Marsh from CHOP showed us data from a large collaboration where they can correlate EEG signals with disease severity in CDD patients. Both of these types of biomarker are very likely to be used in future clinical trials.

Dr Marsh also updated us on the development of novel clinical scales to measure CDD symptoms beyond seizures run by the ICCRN network. They have completed a first part and they are now tweaking and confirming the new scales, which are looking really promising. And one important bit to highlight: this is a study with over 100 patients, and 100 patients is the size of a Phase 3 trial in CDD so kudos to the patient community for mobilizing to make this work and the biomarker studies possible.

And then Dr Xavier Liogier, from the Loulou Foundation, updated us on the progress around the CANDID study which is run in collaboration with a consortium of companies developing CDD treatments. This study evaluates well-known clinical scales that have already been used in clinical trials but for other diseases, to see how they may apply to CDD. Last year Xavier told us about the first patient having been enrolled. Twelve months later he told us that we will get more than 100 participants by the end of this year and showed us a lot of data for how these scales are able to capture different CDD symptoms. The recruitment graph looked exponential, again showing the tremendous mobilization of the patient community to make the CANDID study possible.

Dr Billy Dunn, former Director of the Office of Neuroscience at FDA and current Senior Advisor to the Loulou Foundation, moderated this session and praised all presenters for the spirit of collaboration in sharing all these data while still in progress, and highlighted the value of building all these biomarkers and scales as a “menu to choose from” to enable complex trials in CDD.

Ulysses biomarker project and exponential CANDID recruitment curve

5. MAKING A GENE THERAPY IS LIKE BUILDING A HOUSE

One year ago, at the 2022 Forum, we through that by the end of 2023 we would have the announcement that one of the gene therapies for CDD had received green light for a trial. We didn’t get this news.

And discussing with some parents at the Forum about the best way to explain to non-scientists the implications of delays in very complex process projects, we came up with the idea of how this is very much like building a house from scratch. You approve the initial design, and the constructor gives you a timeline for when you will get the keys. Then it rarely ever happens as planned. And that is because there are too many steps that can end up taking a bit longer, but this is not a sign that there is a fundamental problem with the house or that you will never get the keys. It may be that pouring the foundation is delayed due to a long winter, the insulation had to be redone, building the skeleton of the house can also unlock some surprise… add to that installations, exterior finishes, then all of the interior work… there are just many steps that impact timeline predictions.

Making a gene therapy is not unlike building a house. The biotech experts know how to make gene therapies, but they still have to adjust each step to our particular gene therapies and there are so many complex steps including regulatory reviews (like the different house inspections!) that timelines end up shifting but that is just a normal part of making a gene therapy.

What we know today is that the gene therapy from Ultragenyx and the one that the Loulou Foundation is developing with UPenn have indeed both already been presented to regulators in 2023, and are both now hoping to get clinical trial approval in 2024. So the progress has been good, just not as fast as we all hoped for. And Sharyl from Ultragenyx was very clear in her presentation this year: they have not found any adverse safety signals with the CDD gene therapy to date in any of their studies in animals including primates. This is a case of having to complete some more extra work to pass the house inspection.

Bottomline: at the end of last year we were told “I think I can give you the keys to the house by the end of next year” and that didn’t happen yet, but there is no problem with the house. It is just really hard to predict the exact timelines in very complex projects.

At the 2023 Forum we also reviewed the progress using new gene therapy modalities that haven’t been yet approved for any human disease so there are no precedents. In particular we had an update from Dr Kyle Fink from UC Davis who has been developing a CRISPR-like approach to reactivate the second copy of CDKL5 gene in each cell in females (from the second X chromosome), and also from Kelcee Everette from David Liu’s lab who is also developing a CRISPR-like approach called prime editing to correct the wrong letter or inset a missing letter in CDKL5 mutated genes. In both cases, much of the work focuses on improving efficiency (more copies of the gene fixed), specificity (not mess up with other genes) and figuring out how to make the CRISPR tools smaller so that they can fit the viruses used in gene therapies. These projects are like building new houses with completely new materials that had never been used before, and that so far are too large to fit well into the house. So timelines are unknown, but progress is very tangible. And it is quite amazing to see that one of the first diseases that these new technologies are being applied to is precisely CDD.

Multiple gene therapies in development

6. TWO SUPRISES THAT HAVE OPENED TWO IMPORTANT NEW DOORS

Not everything is taking longer than we thought. Some things are happening faster than we thought. We saw two great examples of this at the Forum.

Learning from evolution

Dr Ibo Galindo from the CIPF presented a fascinating evolutionary analysis of CDKL5 from the first single cell that existed and throughout the entire tree of life. It turns out that plants had CDKL genes but lost them (they have CDD!), and the original CDKL gene was CDKL5 but then it got duplicated twice leading to 5 forms. And it turns out that while all CDKL1-5 forms appear to be important to control cell skeleton, CDKL5 seems to have acquired new functions in vertebrates. There were two important conclusions: (1) there is probably functional redundancy among CDKL proteins, and (2) CDKL5 has a unique tail in vertebrates that suggest a new function not related to cytoskeleton.

And those conclusions provide a beautiful context to two projects coming from the lab of Dr Sila Ultanir at the Crick Institute that I summarize below. Sila’s lab was awarded the Lab of the Year Award by the Loulou Foundation in this last Forum, but I like to call them the “Lab of the Decade” because of their major ongoing contribution to the CDD field.

(1) Functional redundancy. Found the right paralog. Found a new therapeutic avenue.

A paralog is a gene that was born from a duplication of another gene, so now the two copies are so similar that they might have overlapping functions. This is what happened in SMA, the neuromuscular disease that is lethal in babies born without any functional SMN1 gene, that is now treatable because scientists found a way to use SMN2 (a paralog!) to compensate for the loss of SMN1.

Sila’s lab found that the most famous cytoskeleton target that we know for CDKL5, called EB2, wasn’t only controlled by CDKL5 in neurons, there seemed to be another kinase that could do the same job. And it turned out to be CDKL2! So now she is looking into the possibility of upregulating CDKL2 to compensate for the loss of CDKL5. And there is a potential to achieve this using an ASO approach. At the Forum we had a wonderful lecture by Dr Stanley Crooke, who founded and led Ionis (the company that made the first ASO treatment for SMA) and later created a non-profit organization called N-Lorem to make ASOs specifically for people with nano-rare diseases. And he explained that “CDKL2 has nice architectural features to make it suitable for overexpression” using ASOs. And he knows about this!

It has been quite unexpected to find out that we might get to follow the steps of SMA by finding a second gene that could do much of the work of the first gene (at least in neurons, because looks like in other organs it could be another CDKL). And this happened super-fast.

(2) Predicted to have targets beyond cytoskeleton. Found the right target. Found a new therapeutic avenue.

Dr Marisol Sampedro, working in Sila’s lab, had made the discovery last year that CDD could be partly a channelopathy because she found a new target for CDKL5 that is an ion channel. The channel is called Cav2.3, and when it is not phosphorylated by CDKL5 (as would happen in the deficiency) the channel stays too open, and the neurons stay too active. So what we would need is inhibitors. You can read about this in last year’s Forum recap (point 4, where I called this discovery a breakthrough).

One year later we had a new company standing on stage, called Lario Therapeutics, telling us that they are developing Cav2.3 inhibitors for CDD and for a disease caused by gain-of-function mutations in that gene (so they also have too much activity). Lario’s chief scientist explained that they are close to finishing the chemistry optimization and to start running safety experiments to advance their new drug towards clinical trials. This is a precision medicine approach to treat CDD and this seriously happened super-fast.

SUMMARY: MOMENTUM

We learnt this year that the first gene therapy is taking a bit longer that we thought, but many other things are happening faster than we thought, including having new therapeutic avenues (CDKL2 and Cav2.3) that were unimaginable for us barely 2 years ago. We also had several multi-year-long efforts all give us tangible results finally this year, like the two observational studies that have recruited as many patients as Phase 3 trials, or finally having beautiful in vitro and in vivo epilepsy CDD models of the type that pharma companies need. It feels to me that the pace of progress is accelerating, almost like that recruitment timeline for the CANDID study, and we have reached a powerful momentum.

That is exactly the same word that Stan Crooke chose when he stood on stage, and told us how “you can feel the momentum behind the science” in the CDD space. And I think that is a good word to capture what we saw this year.

And this momentum builds on two pillars that were also mentioned often during the 2023 Forum: determination and the spirit of collaboration.

Voice of the patient at the 2023 CDKL5 Forum

So I will leave you with quotes from three of the parents that spoke at the meeting that capture some these messages:

Cristina, from CDKL5 Spain, reminding us that “People with CDD are amazing and they deserve the best”.

Majid, from the Loulou Foundation, acknowledging the road to come with “We have moved faster and further than I expected thanks to all of you. And at the same time, that’s never as fast or as far as hoped for by the families”. He then called upon the audience to recommit with even more passion, more drive and more determination.

And Heike, representing the CDKL5 Alliance, who told us about his daughter and her personality, the efforts that all countries in the alliance and doing at the local and international level, and how “together we are stronger”.

I know I say this every year, but this was the best CDKL5 Forum so far.

I hope you enjoyed this summary. Please let me know your thoughts in the comments.

Ana Mingorance, PhD

Disclaimer: This is my own summary and key learnings, and not an official text about the Forum by the Loulou Foundation. I write these texts with the parents of people with CDD in mind, so excuse also my lack of technical accuracy in parts.

Dónde está la mutación de tu hijo en CDKL5, y qué nos dicen los gemelos

Una conversación que suele salir mucho en reuniones de familias CDKL5 es la posición de la mutación de sus hijos en el gen, por si eso nos ayuda a saber la severidad de la enfermedad cuando crezcan. Os resumo abajo un listado de publicaciones y sus conclusiones.

Una conversación que suele salir mucho en reuniones de familias CDKL5 es la posición de la mutación de sus hijos en el gen, por si eso nos ayuda a saber la severidad de la enfermedad cuando crezcan.

Yo sé que hubo estudios que decían que las mutaciones hacia el principio del gen son peores, y que si son mutaciones hacia el final “como tienes casi toda la proteína” dan lugar a cuadros clínicos más leves.

Pero también sé que hoy en día ya no se cree en esa correlación. Pero para estar seguros he mirado la literatura para ver si aún creemos que hay correlación entre mutación y fenotipo, o si no. Os resumo abajo un listado de publicaciones y sus conclusiones.

Nota para el lector no experto:

Genotipo es el tipo de mutación

Fenotipo es el cuadro clínico, los síntomas)

2004 - Mutations of CDKL5 Cause a Severe Neurodevelopmental Disorder with Infantile Spasms and Mental Retardation

Artículo original que identifica CDKL5 como la causa del síndrome. Describen una familia que tuvo 5 hijos, y eso incluye dos sin problemas, un varón que se les murió con 16 años con discapacidad intelectual several y epilepsia, y gemelas idénticas ambas afectadas. Eso es lo que llevó a los médicos a buscar la causa genética más que probable del problema de los tres hermanos, y encontraron que era CDKL5. Ahora eso eso, una de las gemelas idénticas tenía un cuadro clínico de “síndrome de Rett” (que resultó ser CDD) mientras que la otra, gemela idéntica, solo tenía trastorno de espectro autista. Basado en las descripción, con la misma mutación, el hermano tenía un fenotipo muy severo, una de las hermanas un CDD promedio, y la otra muy altamente funcional.

La familia 2 tuvo también dos casos, ambas hijos d ella misma mujer aunque de diferentes padres. Una considerada Rett atípico porque siempre estuvo muy afectada, y otra Rett clásico porque empezó mejor y a partir de los 3 años perdió uso de manos y dejó de adquirir más capacidades motoras. Misma mutación.

Con estas dos familias, sobretodo con las gemelas idénticas, está claro que sabiendo la mutación NO puedes saber si será más o menos afectado.

2012 - Recurrent mutations in the CDKL5 gene: genotype-phenotype relationships

Miran a niños que llevan la misma mutación en CDKL5 y si se desarrollan de forma igual. Ven que hay una mutación repetida (una missense, de cambio de letra) que produce casos más ligeros, pero todas las otras repetidas más severos. Y de esas las hay hacia el principio y hacia el final.

2012 - What We Know and Would Like to Know about CDKL5 and Its Involvement in Epileptic Encephalopathy

Explican “hasta ahora no se ha visto correlación clara de genotipo-fenotipo en casos de mutaciones en CDKL5. Algunas publicaciones sugieren que mutaciones hacia el final del gen dan lugar a cuadros clínicos menos severos, pero otros argumentan que la naturaleza de la mutación no tiene impacto en el espectro clínico. Por ejemplo el estudio de Weaving y colabores que describe dos gemelas idénticas con un fenotipo muy opuesto, una con un fenotipo que concuerda con Rett y la otra con espectro autista pero de discapacidad intelectual leve. Como se les miró la inactivdación del cromosoma X y ambas lo tenían normal, se piensa que su diferencia de fenotipo se debe a genes modificadores o factores ambientales"

2014 - Mutations in the C-terminus of CDKL5: proceed with caution

Algunos casos de mutaciones cerca del final del gen se ve que estaban mal interpretados, que se los había considerado patogénicos pero no eran porque eran heredados de los padres (todos llevamos muchas letras cambiadas en nuestro ADN, la inmensa mayoría de las veces no son problemáticas). Avisan de que las mutaciones en los exones 19’21 podrían ser falsa interpretación y tener cuidado con esos resultados genéticos.